Rally 'Round the Cannon

Launched 50 years ago, the $53 Million Campaign was a classic success

Success has many fathers, but failure is an orphan. (Old Hindi adage so successful that many people take credit for it)

Over the summer, with little fanfare – likely the best approach when the economy is in the tank and a huge chunk of the populace is un- or underemployed – the current Princeton capital campaign (“Aspire” to you irrepressible poetic types) passed the $1 billion milestone. In my world, $1 billion actually qualifies more as a Las Vegas resort than just a milestone, but you get the idea. So it seems timely to cast a backward look here at History Central to the very first such capital effort, which kicked off 50 years ago.

So the University says now (coyly, it is referred to as “the first official fundraising campaign”). There’s been loads of attendant publicity highlighting the admittedly impressive results of that $53 Million Campaign and its successors, A Campaign for Princeton ($410 million raised, 1981-86) and the Anniversary Campaign ($1.14 billion, 1995-2000).

In reality, there was the President’s Program in the 1930s and the Third Century Campaign after World War II, not to mention other false starts that lacked names to be forgotten. Ever hear of them? I can pretty much guarantee you never will again; they have fallen into the historical abyss of many, many orphans before and since. They might not even be noted here but for an astounding effort by this, Your Favorite Periodical. After the $53 Million Campaign succeeded, editor John Davies ’41 commissioned a 20,000-word post mortem by Peter Spackman ’52 (published in the May 11 and 18, 1962, editions of PAW) which with modest tweaks could be a primer for every successful large college campaign conducted – at Princeton or anywhere else – since. And Davies preceded it with a full-page unsigned editorial detailing and excoriating the University’s prior capital efforts (“repetitive grandiose announcements” is one of the tamer phrases) to set the blunt context for such an extraordinary study, and to highlight how amazing the results were, especially to veteran Princeton observers.

The roots of that success actually lie in the aforementioned (non-official?) Third Century Campaign, launched in the heady days following the bicentennial celebrations of 1946-47, when Princeton seemed to be the center of the postwar universe. Volunteer Harold Helm ’20 had been running the amazingly popular Annual Giving (45 percent of alums gave annually) through the tumult of the war; but nobody talked to him. There was one campaign office; it was in Manhattan, run by well-heeled alums who apparently spoke mainly to each other. Fewer than 500 people were involved in soliciting. The staff carefully documented $54 million in University needs, $20 million of which was urgent; but no goal ever was announced. In two years, they dug up only 600 donations totaling $1.33 million. Just before the trustees pulled the plug in 1948, they handed the ruins to Helm; this afterthought united annual and capital fundraising in a bond that hasn’t been broken since.

It took eight years and a chunk of atonement by the trustees to crawl back from the (nonexistent?) Third Century Campaign. In 1956 they finally established the development office to institutionalize fundraising, but by then President Harold Dodds *14 was a lame duck, and any major capital campaign required a new face.

When the trustees offered 37-year-old classics assistant professor Bob Goheen ’40 *48 the presidency that year, search committee member Pitney Van Dusen ’19 took him aside and assured him the University was in strong financial shape, and he wouldn’t have to worry about raising money. Aside from wondering how many trustee meetings Van Dusen may have missed to arrive at that conclusion, even the scholarly Goheen knew that sounded unrealistic, especially given the expertise of the chairman of both the trustees and the search committee.

Harold Helm.

Helm and Goheen hired a professional fundraising firm, a Princeton first, and with the new development office set about some very heavy lifting. The seriousness and tension started upfront: Helm wanted fellow New York financial power exec Jim Oates ’21 to run the effort. Oates said fine, I’ll do it if 100 percent of the trustees donate before the campaign is announced. The last stragglers came in a few days before the Alumni Day unveiling in February 1959. The trustees alone were in for $4.3 million, more than triple the entire Third Century yield; eventually that would grow to $7.5 million.

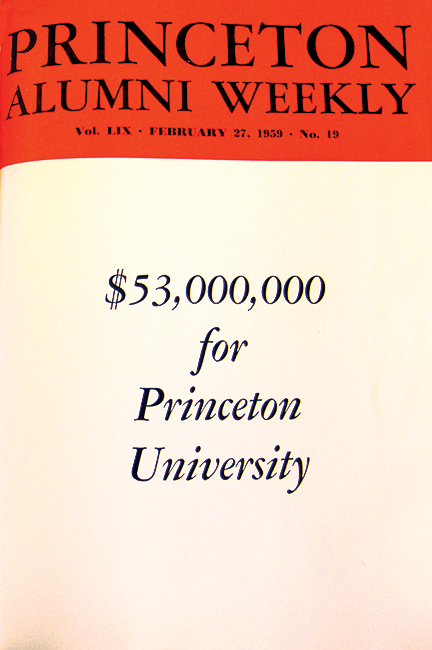

The cover of PAW on Feb. 27 was white, with huge black letters:

No goal confusion here, dude; Goheen and Oates spent more than four pages inside meticulously laying out the case to “contribute in ways of prime significance to the well-being of our nation and the world.” So there. It was a stretch to be sure – the pros thought the alumni community just might be good for $50 million to $55 million – but the list of immediate potential projects – the Old New Quad, the engineering quad, the new music building, the architecture school, Caldwell Field House, etc. – seemed endless, and Oates certainly had a direct approach to donors about parting with their money: “You can’t take it with you. It’s reputed to be the root of all evil. And it’s tax-deductible.”

The first six months were spent soliciting potential $100,000-plus donors and building an organization. There were eight regional offices, from Atlanta to Boston to Los Angeles. Almost 5,000 volunteers ended up working on the campaign as it broadened. Forty-six leadership conferences were held across the world. Publicity was incessant: The $53 Million Newsletter” went out a few times a year to more than 44,000 people; campaign updates hit The New York Times frequently; major gifts (Rockefeller $1 million, Danforth $1 million …) were highlighted immediately; every new groundbreaking and building dedication (Hibben apartments, Moffett Lab, Finney Field, etc.) was promoted to the skies.

Bob Goheen spent one-third of his time for three years on the campaign, traveling usually with Helm (but presumably not Van Dusen) and developing the University’s story for a vast array of audiences; he even flew to Chicago just to speak to alumni wives and widows. His usual handwritten notes for his speeches survive; dozens upon dozens of 3x5 cards with tiny script (that might as well be Greek to anybody else) with cautions: “LOW & SLOW” and with reminders of the audience: “Pton is important,” “PLURALISM,” “Athletics.” The urgency, remarkable in such a reasoned, calm man, is still palpable.

After a year, things were running full bore, and by Alumni Day 1960 more than $22 million was in hand. A year later the total was $36 million, but the stock market wasn’t cooperating; the closing date, always a bit squishy, was set for Alumni Day 1962 to give the volunteers a hard deadline. With four months to go, the total stood at $44 million and it looked like a close call; big sources were almost exhausted. Then, with only a month to go, out of left field came New York financier Shelby Cullom Davis ’30 with a dramatic $5 million to put the campaign over the top. The news of this drove a flurry of last-second gifts out of the woodwork, and the final take for the $53 Million Campaign was $60.7 million (10 percent more than the fundraisers’ maximum guesstimate) from an astonishing 17,925 donors. During the last year of the campaign, more than 80 percent of the living undergrad alums had donated to Princeton, either through the campaign or Annual Giving.

A very important point, that. Unique among colleges to that time, Princeton had consciously chosen to keep AG going during the capital campaign; Helm, ever the AG champion, reasoned that the target audiences might overlap but were motivated differently. This insight had nothing but positive results: AG held steady, bringing in more than $4 million in the three years, setting a new record in 1961-62; the campaign beat its target; and the summary report for the drive included the names of all who contributed to either one during the three years: more than 28,000 people, including 83 percent of the undergraduate alums and hundreds of grad school alumni as well. This model would be reinforced in subsequent campaigns, which not only included Annual Giving in their target amounts but were structured to run over five years, giving every class a shot at one major reunion drive in the duration. Remarkably, these two tweaks (with a respectful nod to the Internet, of course) have been the only major visible changes over the ensuing 50 years of Princeton campaigns.

The success of the $53 Million Campaign, concretely expressed in buildings, faculty chairs and endowment, is remarkable enough in contrast to the half-century of prior fundraising fiascos noted by PAW so long ago. But it also gave significantly added clout to its leaders that would have a huge impact on Princeton in the next tumultuous decade. Goheen was instantly an administrative force, not just an academic; he now had the leverage to begin serious change where it was needed. Oates succeeded Helm as the chairman of the trustees, and steered them through Vietnam and coeducation. And Helm, crucially, was put in charge of the trustees committee on coeducation in 1967. Initially an opponent, he wrote the committee’s favorable report in 1969, essentially ending debate and clearing the way for women undergraduates. The Princeton that Bill Bowen *58 inherited from them in 1972 bore only passing resemblance to the old one imagined by Pitney Van Dusen in 1956. Bowen’s Campaign for Princeton reached its five-year goal in less than three years.

No responses yet