Rally 'Round the Cannon

45 years ago, an All-American and the single wing led Princeton football to an undefeated season

On Nov. 14 at the Yale Game, the University celebrated its most recent undefeated football team. It’s nice that most of the players are still around, if only to pointedly show the denizens of the current program that it’s a rational goal, but that isn’t the topic here; instead, there’s a more substantial lesson to be gleaned from that remarkable team of 1964. It’s a tale of opportunistic triumph over confusion, of focus and simplicity as creative forces, in a phrase, the Triumph of the Single Wing. And ironically, it was accomplished by starving the offense.

If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs…

… you’ll be a Man, my son.

-- Rudyard Kipling

For, you see, the college football world in 1964 was a complete shambles. In the early 1950s, the NCAA had gone on a cost-saving kick and instituted one-platoon football, essentially eliminating specialists and emphasizing all-around athletes who could survive for 60 minutes. This held sway for 12 years, then was reversed after the ’63 season. Coaches and players comfy with 11-man football suddenly had more than 50 percent of their slots open. Given the honored tradition of intellectual flexibility in football, panic ensued.

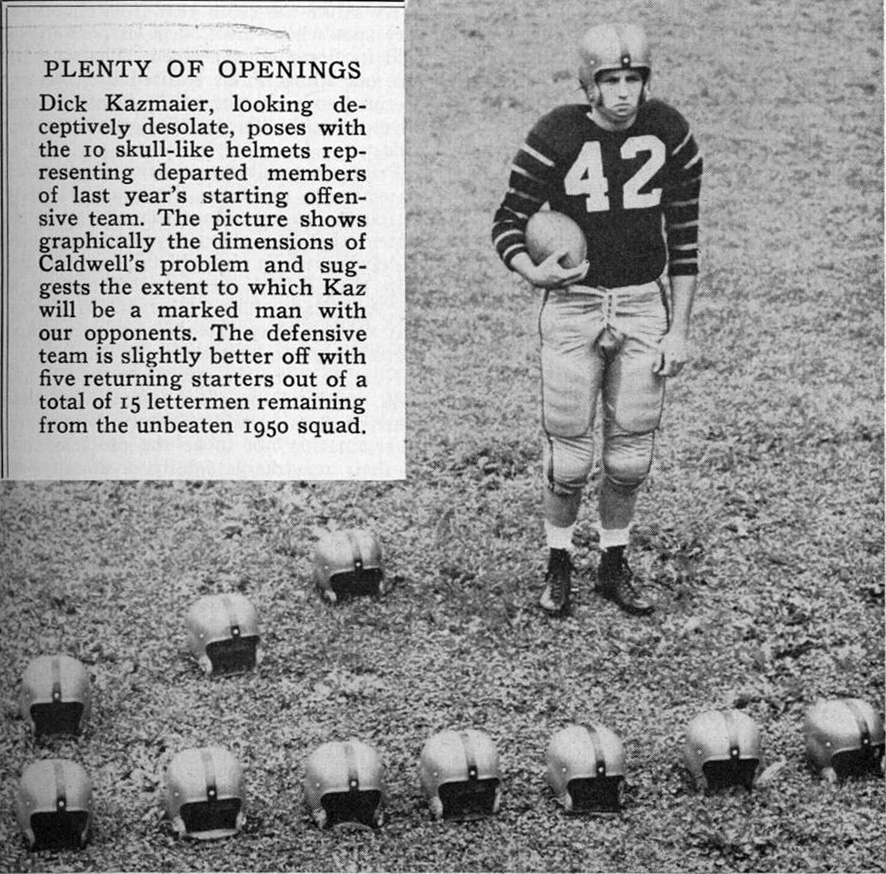

Princeton, coming off a strong 7-2 Ivy co-championship season (concluded, however, with a galling 22-21 loss to its nemesis and co-champ, Bob Blackman of Dartmouth), had an unfair advantage: Coach Dick Colman not only read books, he was something of an historian. He recalled enough, for example, to stay firmly with the single-wing offense, a gutty creature of unbalanced line play and direct snaps to the tailback/runner/passer, perfected in Palmer Stadium by his predecessor and mentor, Charlie Caldwell ’25, in the ’40s and ’50s. As college teams had gone rapidly to the sexy T-formation, opponents found the Princeton single wing increasingly hard to defend against, since they got no exposure to it otherwise. Colman also recalled the 1951 Princeton season, symbolized by one of the great photos ever run here in Your Favorite Periodical:

Princeton, coming off an undefeated Lambert Trophy year in 1950 and amid Heisman buzz surrounding All-American tailback Dick Kazmaier ’52, had no other starters back on offense. Caldwell, who actually wrote books, had responded counterintuitively: He gathered up his 11 best athletes (apart from Kazmaier) and put them on defense, reasoning that it would give the offense time to round into shape: The goal was to win games, not Heismans. Sure enough, the Tigers’ production dropped from 39 points a game – to 34 – but they shut out their three toughest opponents, Brown, Yale, and Dartmouth, and went undefeated again. Poor Kazmaier took one for the team: His per-carry average dropped from 6.0 yards (insane) to 5.8 (astounding), but he did manage to salvage the Heisman. Close call.

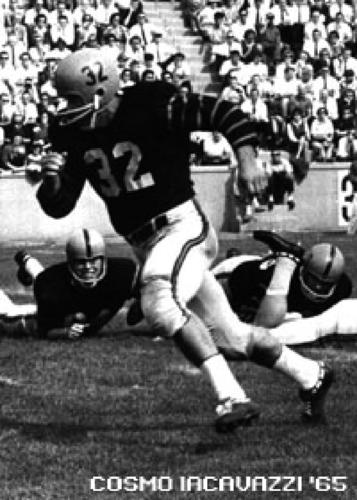

So Colman, when two platoons came around again in 1964, took his experienced, fast guys and put them on defense. The exception (well, sort of; he actually was the only Tiger who consistently still played both ways) was Cosmo Iacavazzi ’65 *68, the intimidating first-team All-American fullback who had tied Hobey Baker ’14’s Princeton season touchdown record the year before. Iacavazzi punished people in both directions, and was encouraged to continue.

The Ivy League picture was a muddle; every team other than Penn (ah, those were the days!) was given some sort of chance, and even the ’63 co-champs had finished 5-2, hardly awesome. So when the Tigers started off with three- and 10-point home wins over mediocre Rutgers and Columbia, the lack of experienced offense became alarming.

Especially since the next game was the Tigers’ first-ever trip to Hanover, N.H. Somehow, the strange journey to the wild land of black bears and Blackman created the offensive focus that had been lacking. It was 10-0 at the half and 20-0 at the end of the third quarter, and Princeton got its revenge for the prior year, 37-7. Almost 40 percent of the offense was through the air, ideal for the single wing. This was followed by offensively lackluster home wins over Colgate 9-0 and Harvard 16-0, a 14-0 bruiser at Brown with Iacavazzi getting 178 yards, and a 55-0 plastering of awful Penn at Franklin Field, in which Princeton had 360 yards rushing and Penn crossed midfield for the first time with two minutes remaining. Colman noted that the defense, with Stas Maliszsewski ’66 doing a passable version of Illinois’ fearsome linebacker Dick Butkus, was superb (seven points total allowed in five games – ya think?), and the offense was “making strides.”

This was all prelude to a ballyhooed showdown for the Ivy championship in New Haven, with 6-0-1 Yale and 7-0 Princeton duking it out in front of 60,000 fans – the first time since 1906 the two had met with both unbeaten. Yale scored on its opening drive, becoming the only team to hold a lead on the Tigers the entire season – for less than 13 minutes. It was 14-14 at the half, with Yale’s Chuck Mercein moving the ball as no one had done on Princeton all year. Then finally, after eight games of inconsistency, the Tiger offensive line in the second half solved the nuances of single wing blocking (by themselves; Colman literally said nothing to them at halftime) and simply wouldn’t surrender the ball; Iacavazzi had 185 yards on only 20 carries in the highlight game of his career, the team ended up with 354 yards on the ground, and Princeton never punted after the first quarter. Final, 35-14 Tigers.

All that remained for the new Ivy champs was a 3-4-1 Cornell team that was dangerous offensively, having scored 118 points in its last three games. But the big problem again was Princeton’s offense because the game was in Palmer Stadium, where the team mysteriously was averaging 14.5 points per game, as opposed to 35 on the road. Sure enough, the Tigers went up 14-0 at the half, then went into early hibernation; the 17-12 final was closer than it needed to be. Indeed, the most important stat was on the defensive side: Maliszewski had 19 tackles, every one of which was needed. Colman’s defend-and-conquer strategy in the beginning made itself known to the end.

Indeed, the undefeated Tigers had regressed from 28 points per game (although only to 24, thanks to their mystifying productivity only on the road) but were undefeated, since the defense had given up a grand total of 53 points in nine games. Meanwhile, the afterthought single wing just did what it did best, controlling the ball: Iacavazzi ran for 909 yards (5.3 per carry), tailbacks Don McKay ’65 and Ron Landeck ’66 ran for 632, and the team threw only eight passes per game. They scored more against Penn than the defense allowed all year. They gave away a minuscule 12 turnovers the entire season while the veteran defense collected 30, a differential of fully two per game. Iacavazzi repeated as first-team All-American; fittingly, Maliszewski joined him (and Butkus).

“So, do you like Kipling?”

“I’m not sure; I’ve never kippled.”

-- Joke approximately three days younger

than Rudyard Kipling

If you’re a football fan (an admittedly dangerous fixation for a Princetonian these days), lately you have been amused if not transfixed by the breathless hoopla surrounding the current NFL “surprise of the decade” (in the ’80s it was the West Coast offense; in the ’90s it was the alternate third jersey, as far as I can tell): It’s the Wildcat! The novel offense is in reality Charlie Caldwell’s single wing, of course, being executed by kids who think it’s new and cool and don’t know how to do it very well. Better they should remember Charlie as Dick Colman did, and stick to defense.

No responses yet