… the more complete map of Mrs. Obama’s ancestors… for the first time fully connects the first African-American first lady to the history of slavery, tracing their five-generation journey from bondage to a front-row seat to the presidency.

—Rachel Swarns and Jodi Kantor, The New York Times

I am bound, you are bound, to everyone on this planet by a trail of six people.

—Ouisa Kitteridge, Six Degrees of Separation

The New York Times’ recent genealogy study of Michelle Obama ’85, noting for the first time her slave and mixed-race heritage, seemingly surprised a broad swath of the populace. This indicates that we here in the History Corner of the World haven’t been doing our jobs very well. The complex intertwining of peoples and cultures living side by side for hundreds of years, their humanness grotesquely masked by slavery and then gratuitous segregation, is as near a universal experience as you can find in the United States. We were all involved; we are all affected. Get used to it.

It is, for a nearby example, pretty much common knowledge that the saga of African-Americans at Princeton began in World War II, and gained no effective traction until the Goheen administration in the 1960s. A whites-only world, if ever there was one.

Let me instead tell you a story more than 200 years old.

Sal and Charles were born at the beginning of the 19th century. They were a “Negro girl and boy” who were the property (the word slave is never used) of John Maclean Sr., the Princeton college’s renowned chemistry professor. We know of them only because they appear on Maclean’s estate inventory after his death in 1814. Charles was then on lease to John Vanhorn for six years. Slavery would not be abolished in New Jersey until 1846.

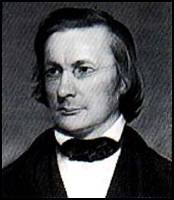

John Maclean Jr. 1816 was 14 years old when his father died, so he obviously knew Sal and Charles well. Academically precocious, he already was a Princeton student. He would go on to be the College’s binding force through the lean times of the 19th century as faculty member, vice president (co-president, really) from 1829 to 1854, and president from 1854 to 1868. Also a Princeton Seminary graduate, he was a beneficent force in the community. Among countless other good works, he was a founder of the First Presbyterian Church of Color of Princeton in 1846, renamed the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church two years later. He ceded his college presidency to James McCosh when he retired in 1868, and was revered throughout the College and town until his death in 1886.

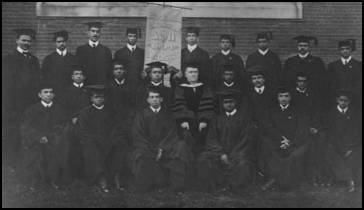

Isaac Norton Rendall 1852 was a student of Maclean’s who took his lessons seriously; while an undergrad he taught Sunday school at the Witherspoon Street church. Like Maclean a Princeton Seminary alumnus, in 1865 he became president of the 11-year-old Ashmun Institute in Pennsylvania – renamed Lincoln University the next year – the first degree-granting college for black students in the country. He was president for 41 years, establishing a rigorous curriculum and standards for the school. Many Lincoln alumni sent their children back to him because, as one said, “I wish my son to be in an institution where students are treated as if they were made in the image of God.”

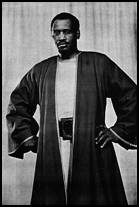

William Drew Robeson Sr. was born a slave in North Carolina in 1844; he escaped to Pennsylvania via the Underground Railroad in 1860. After laboring for the Union Army in the Civil War, he was accepted as a student of Isaac Rendall at Lincoln and graduated with a theology degree in 1876. Four years later, when Maclean was 80, Robeson was hired as pastor of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church, where he served for 21 years. He sent his oldest son, William Drew Jr., to study at Lincoln with Rendall; he became a physician.

Paul Robeson was William Sr.’s fourth son, born in 1898 in Princeton. They lived at 110 Witherspoon St., next door to the church and the current-day Paul Robeson Center for the Arts of the Princeton Arts Council. He attended a segregated elementary school in town. His father was tossed out of the church in 1901 after a congregational schism; by 1910 William Sr. was pastor of Saint Thomas AME Zion Church in Somerville. The schools there were integrated, and Paul became an academic and athletic star at Somerville High School. He won a competitive full scholarship to Rutgers, where he was one of two black students. He was an All-American football player and valedictorian of the Rutgers class of 1919, then graduated from Columbia Law School. He went on to become a world-renowned singer, actor, and orator; his politics eventually made him a target of the House Un-American Activities Committee and J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI.

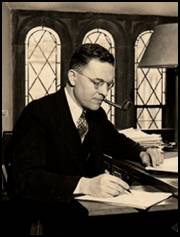

J. Douglas Brown ’19 *28 was Paul Robeson’s academic rival at Somerville High; he called Robeson his “warm and loyal friend.” A Princeton legacy – his brother was a football player – Brown reveled in the classroom and, after two years teaching at NYU, he returned to Princeton for the rest of his career, earning his doctorate and remaining as a professor, dean of the faculty, and the University’s first provost until his 1967 retirement. A giant in the field of industrial and labor relations, he is regarded as the father of Social Security in 1935 and a crucial contributor to Medicare legislation in 1965. In 1955, even before Bob Goheen ’40 *48 became president, Brown told the Princetonian, “To obtain the precious cream of creative talent, a far greater volume of milk must be processed through our education system. Talent occurs in all groups and areas of our population.”

Carl Fields was the first black athletic scholarship recipient at St. John’s University and track captain in 1942. An experienced counselor, he was recruited in 1964 from Columbia to Princeton at Goheen’s direction by Brad Craig ’38, ostensibly to work in Student Aid, but in reality to guide the extremely few black students on campus. He reached out to the black community in town, and became convinced that having a local surrogate family was the only way to help some black undergraduates adjust to the University. His crucial moment at Princeton (PAW, Nov. 18, 1977) was the Nassau Hall administrative meeting in which he pitched his family-sponsor program to the power structure; he already had encountered enough reticence among colleagues that he intended to resign if he was turned down. After significant criticism, the discussion ended abruptly when Doug Brown, then dean of the faculty for 20 years, simply told Fields to go ahead. Brown said he had good friends in the black community, but might not know as much about it as he should, and the family sponsors might very well be helpful. Fields stayed on to become assistant dean of the college, the first black dean in the Ivy League. He helped guide the creation of the Third World Center, which opened in 1971.

Steve Dawson ’70 entered Princeton in 1966 as the initial family sponsors from town began their work. His sponsor was Susie Waxwood, the first African-American president of the Princeton YWCA and elder of the Witherspoon Street church. When the black students formed the Association of Black Collegians (ABC) in 1967, advised by Fields, he served as its secretary. He attended the first planning meeting for the Association of Black Princeton Alumni (ABPA) in December 1972, and served as its president from 1979 to 1984 as well as a member of the Alumni Council executive committee. He became an information-technology executive and consultant.

Michelle Robinson came from a working-class Chicago family and was the little sister of star Tiger basketball player Craig Robinson ’83. She worked long hours at the Third World Center, the extracurricular focus of black culture at the University, and wrestled with cultural-identity issues, hardly unusual among her peers. Dawson hired her to organize on-campus events for the ABPA. Her thesis, “Princeton-Educated Blacks and the Black Community,” examined the relationship of the upbringing of black Princeton alumni to their college experiences to subsequent life decisions, trying to define personal paths for betterment of the black community at large. Her acknowledgements include “special thanks to Mr. Steve Dawson,” who acted as an informal adviser and arranged the extensive survey of ABPA alumni on which the study was grounded. She went on to Harvard Law School and then a number of community-related jobs in the Chicago area. She married Barack Obama, then a lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School, in 1992.

In 2002 the Third World Center was renamed in honor of the late Carl Fields. The original black family sponsors from 1966 were honored there in 2007. Bob Goheen gave the opening remarks; two of the honorees were the late Howard and Susie Waxwood. She had died the previous year at 103, and had attended the Witherspoon Street church for 57 years.

One year later, Dawson worked on the media and technology strategy team of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. Michelle Obama, having become involved in the campaign earlier than planned, inevitably became a central figure. When her Princeton thesis arose as an issue, Dawson helped explain it to the press. Barack Obama was elected.

So there you have a direct path from the slave quarters of Princeton to the White House in less than two centuries. In any practical sense, Michelle Obama is as much a product of John Maclean Jr. and the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church and Paul Robeson as she is of the white man who fathered her great-great grandfather. But the real message of note here is that, even if we limit ourselves to a small town in New Jersey, there are dozens, hundreds of other threads through the black, white, and other communities that tie her to us, that tie us to each other. We were all involved; we are all affected. We are all in this together.

No responses yet