Everybody knows Princeton needs a theater, but I don’t know how to it does,

I mean I don’t know how to say so to people who already know so.

-- Booth Tarkington 1893, in 1926 fundraising mode

One of the apparent casualties of the Great Recession (unless some of the newly recovered Goldman and AIG alums want to intercede, wink, wink, nudge, nudge) is a delay in the new campus arts neighborhood, which was to transform the Dinky Station area into a multi-themed amusement park for the aesthete, complete with studios, stages, galleries, a satellite of the Art Museum and – gasp – even parking. (The immediate undergraduate concern for the project revolves around the fate of the Wawa, but let’s let that one slide for the moment.)

While the arts district is an attractive idea and would set up Princeton as more of a direct competitor to les artistes at Yale – which might be the double-secret plan in the first place – it does serve to point out the vibrant arts neighborhood that already sits right in the middle of the site: McCarter Theatre. It comprises only one or two buildings (depending how you count the wonderful, 6-year-old Roger Berlind ’52 Theater on the south end of the original structure) and may be underestimated by virtually everyone, because most folks avail themselves of one or two or three facets of the gem. But it is the premiere performing-arts location between New York and Philadelphia (in addition perhaps to the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark), and to my mind the key differentiator between a too-cute college suburb and a nourishing community.

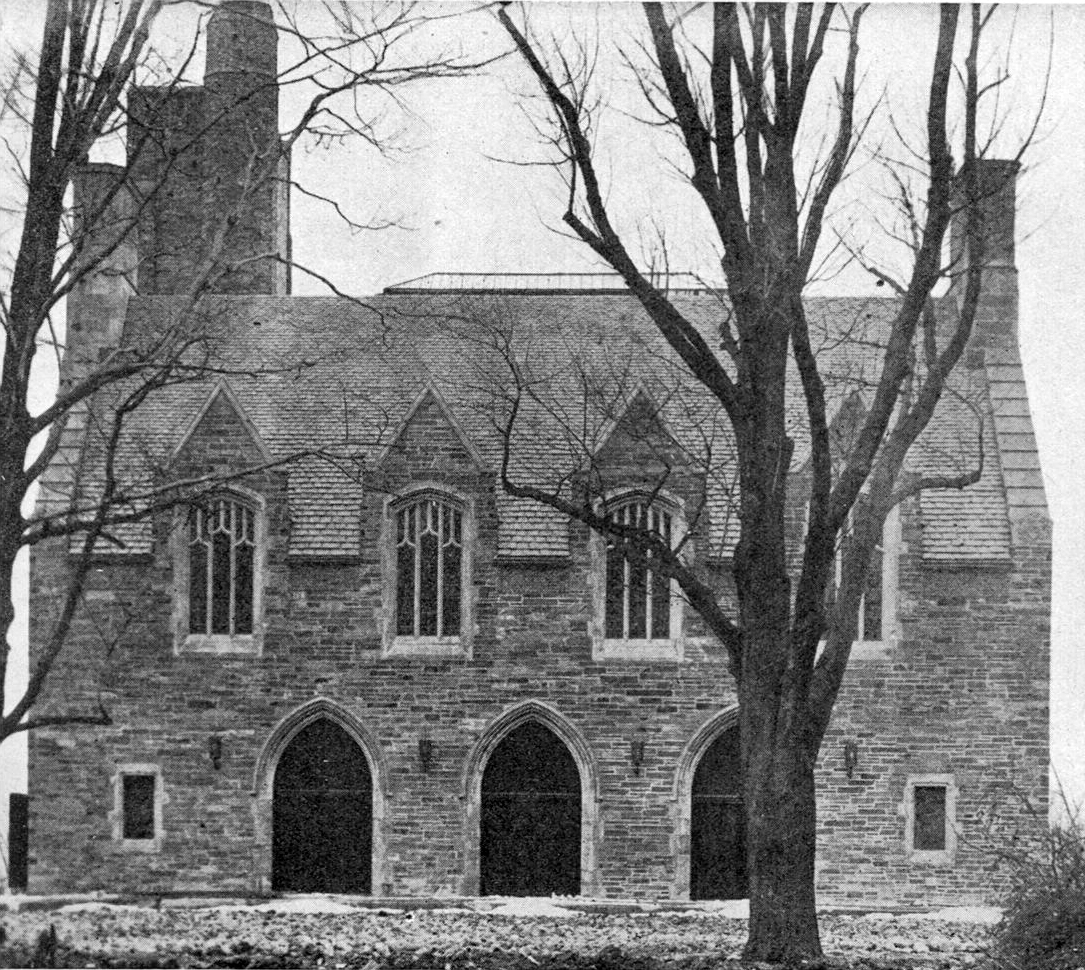

McCarter – the building – arose just 80 years ago as a temple to the Triangle Club. Club members had built the quirky and not-much-loved Casino in 1895 on the same ground, but when that burned in 1924, nobody mourned for long. Triangle was stuck performing its shows in Trenton; while that was a convenient punch line for the show, it couldn’t persist. The club cobbled together $100,000-plus of its own pun-induced funds and $250,000 from Thomas McCarter 1888 and groveled for a bit more via the shepherding of founding spirit Booth Tarkington (above), then opened its new 1,100-seat palace with the Triangle Show The Golden Dog in 1930. The club’s momentum had been building since World War I and was in full flower; in that single production on McCarter’s opening night were:

- Josh Logan ’31, eventual author of Mister Roberts and South Pacific and famed Broadway producer, Tony and Pulitzer Prize winner

- Myron McCormick ’31, a Tony-winning stage actor in the original South Pacific who was memorable in the films The Hustler and No Time for Sergeants and a slew of ’50s TV series

- Norris Houghton ’31, legendary Off-Broadway founder of the Phoenix Theater and author

- Jimmy Stewart ’32 (on accordion, no less), No. 3 on the American Film Institute’s list of all-time movie leading men (right between Cary Grant and Marlon Brando)

- Jose Ferrer ’33, intellectual actor/director on Broadway (Tonys for both), where he and Paul Robeson still hold the record for the longest-running Shakespeare production (Merchant of Venice ); also the only person to win a Tony, Oscar, and Emmy for the same character: Cyrano de Bergerac.

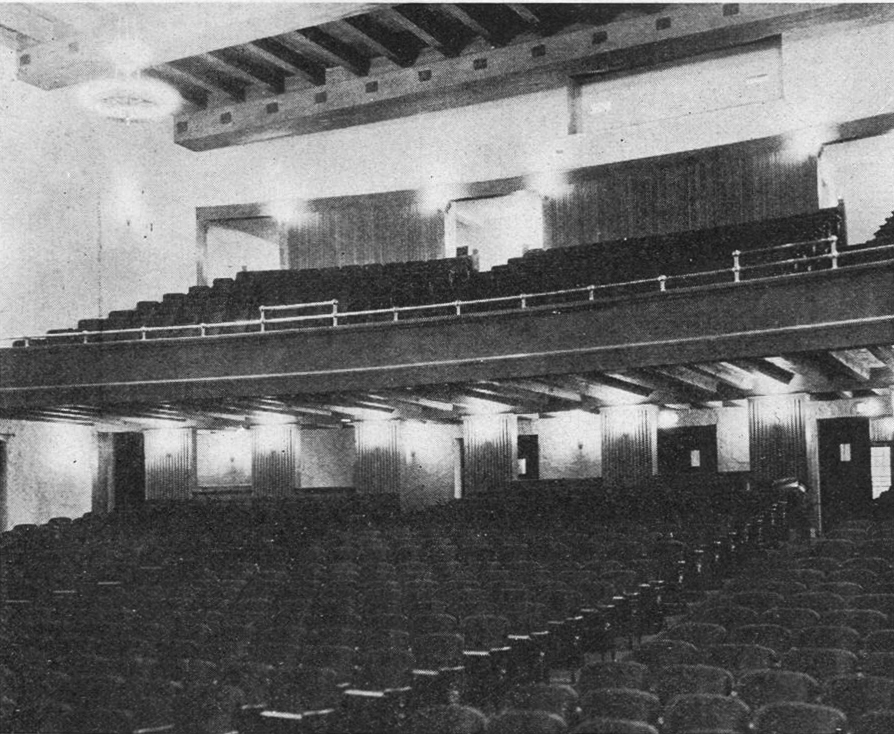

A wonderful performance space (just ignore the quirky brick gothic arches), McCarter was instantly a hit, used by campus and local groups doing everything from Triangle to Plautus to student-authored plays to community fundraisers – all in its first six months. But of course the theater opened just in time for the Depression, and the resulting effect on the arts was the same as now – Triangle started losing road bookings and donations, and keeping up McCarter rapidly became problematic.

Broadway partially came to the rescue in an era when out-of-town tryouts close to New York were preferred: The proto-American Our Town of Thornton Wilder *26 had its world premiere at McCarter in 1938. Major musicians, even the Philadelphia Orchestra, were starved for appropriate space outside the major cities and also came through frequently. But after World War II the outside bookings waned, and the University took over the building out of sheer financial necessity. A faculty committee study in 1960 resulted in a practical idea (this tends to happen once every decade or two, likely a tribute to Heisenberg): Milton Lyon was hired to turn McCarter into a producing theater. This was hardly a brilliant insight; he had been directing Triangle shows for five years and was already well on the way to becoming one of the best-loved characters on campus. He created the first professional theater company resident on a college campus in the country.

By the early ’70s, McCarter was a haven for high-quality dramatic revivals under Lyon’s successor, Arthur Lithgow (John’s father), and combined with Lockwood’s tireless impresarianism as a solid base, the University happily spun off the facility and its operations into the McCarter Theatre Center (God forefend we should spell it t-h-e-a-t-e-r), the separate not-for-profit that prospers to this day. Emily Mann, the theatre company’s director since 1990, has been responsible for a series of world premieres, including her own wonderful Having Our Say, and a Tony Award as Outstanding Regional Theater. The 360-seat Berlind has added opportunities for all the McCarter entities as well as for student productions to offer even more programs, and the result today is one of the finest examples of American artistic vibrancy you can find.

In the murky realm of the Law of Unintended Consequences, it is very possible that the long-ago demise by flame of the Casino may deserve a major prize among the many serendipitous events in the University’s history, not to mention those of the town and Mercer County. It’s hard to imagine that Tarkington’s 1920s proselytizing (somewhat oblique, as you can tell) would have been successful had the old rattletrap survived, and McCarter might have faced the same wait as Firestone Library through the Depression, if not longer (the student center, another portion of the 1926 Center for Undergraduate Life project that included McCarter, finally got built in 2000). Where would Bill Lockwood have ended up then, instead of being the Princeton cultural magician that he is? In fact, it’s a shame, if only as a bow to many generations of townies, that he didn’t make the hallowed PAW list of the 25 most influential Princeton alums.

Of course, Thomas McCarter and Jimmy Stewart (even with his accordion and guitar) didn’t, either. Perhaps they would at Yale.

No responses yet