And so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

– Nick Carraway, The Great Gatsby

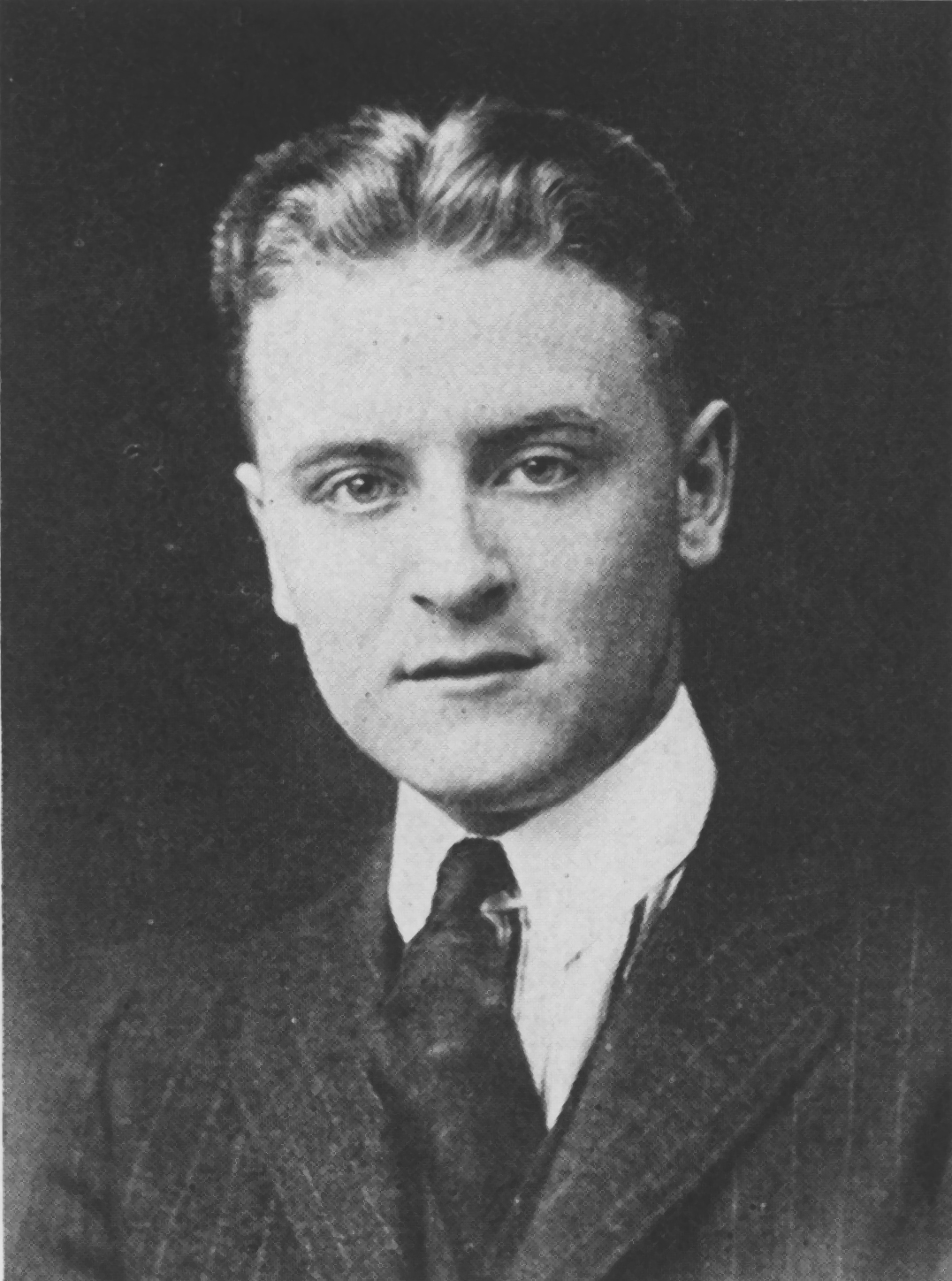

In three years, we’ll actually be referring to him as F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917. In April 2013 the Class of 2017 pops into being, and Fitzgerald’s epoch, always otherworldly in many important senses anyway, officially will be of another century.

He and Zelda Sayre were married 90 years ago, a week following the publication of This Side of Paradise – a convenient juncture that allows us to dwell on the vicissitudes of celebrity, the strengths of literature and ideas, and the weaknesses of humankind. Since Fitzgerald died only 20 years later with a copy of PAW in his hands (making notes about the football team, which regrettably over time has had that effect on others, too), we here at Your Favorite Periodical owe him no less.

But as mesmerizing a paean as This Side of Paradise is, as much as Fitzgerald went nuts for Hobey Baker 1914 (greetings, brand-new Class of 2014!) and the Triangle Club, he fit far better with the Prospect Avenue end of Princeton than the Pyne Library side. His class card resembles more a World War I battlefield than an academic experience; leaving Princeton for the war after two unsuccessful assaults on his junior-year academic load may not have seemed as dramatic a change to him as to us.

Is Fitzgerald’s noblesse oblige Princeton really important anymore? Is there really anything left to say about the Jazz Age, except that he named it? As the tenured history faculty grapples with those – a good cane-wrestling match always cleanses the gray matter, in my experience – why don’t we focus instead on that fateful issue of PAW, and the reason ol’ Scott was probably perusing it in the first place? Let’s look at the Class Notes of 1917; as you certainly should be aware, Class Notes are by far our most-read feature (I don’t take that personally, mostly). Believe it or not, Fitzgerald even kept a chart tracking his classmates.

The ’17 class secretaries faced an 800-pound gorilla from the day This Side of Paradise was published until the day Fitzgerald died, and even afterward: How do you publicly handle a classmate who’s a lightning rod, whose writings and wanderings are the stuff of the gossip mags, whose notoriety more than overbalances the other 483 guys in the class? Let’s take a glimpse at how they did it.

In college, Fitzgerald hardly was the most notable guy in the class, but classmates knew him well. The Class Poll in his Nassau Herald mentions him only twice: as seventh “wittiest,” and very tellingly as fourth “thinks he is.” The die was cast, although perversely he listed as his career goal: “He will pursue graduate work in English at Harvard (??), then he will engage in newspaper work.” Maybe he was just trying to be witty.

In any event, his Army career (mostly in Kansas) appears only perfunctorily among the notes of the extensive military exploits of the self-named War Baby class – 21 of whom (5 percent) died in Europe. But in March of 1919 he showed up at a class dinner in New York while living there, one of the very few organized class events he ever attended; his civilian occupation is unmentioned. Then the following January “it is reported” that a prominent publishing house has accepted one of his books.

The March 3, 1920, Class Notes mention that The Saturday Evening Post is to publish some of his stories – no note of the novel. This Side… came out on March 26, sold out in days, by the next week was a sensation for Scribner’s, and his entire role in the world changed. The effect on his generation was so pervasive that there was a short satire of the book in a class reunion promotion only six weeks later. It was assumed everyone already knew who “Amory” was.

The class secretary notes in May that “most of the characters are members of our Class, and are easily discernable,” and that Scott and Zelda are now married. By December, he notes the “great diversity of opinion” over This Side…, but opines “that [Fitzgerald] is no mean businessman, and is writing a movie scenario for D.W. Griffith for $15,000.” The strangeness of this is hard to overstate: Realize, this is Scott Fitzgerald writing a silent movie. In short order – April 1921, only a year after his first publication – perhaps the most foreshadowing note of all: “Mr. and Mrs. Scott Fitzgerald will sail for the Continent in early May.” He left behind his completed The Beautiful and the Damned for publication.

From that point, common traits in his dozens of PAW Class Notes items accrue rapidly:

He’s removed. Always in the third person (who knows which items were submitted by Fitzgerald, which by classmates?) and never quoted directly, the blurbs have a social-page feel to them: “The Scott Fitzgeralds have returned form Bermuda. …”

He’s famous. Names are dropped: Scribner’s, Esquire, Cavalcade, D.W. Griffith, Gertrude Stein, Edmund Wilson ’16, Jimmy Stewart ’31.

He’s sophisticated. He and Zelda are forever going somewhere, but somehow never arriving for long: Capri, Great Neck, Hollywood, Bermuda, Baltimore, Paris.

He’s the novelist. He is always “working on a novel,” his often-brilliant stories somehow an afterthought. Noted in early 1923, The Great Gatsby comes out in 1925. Already promised in 1926, Tender Is the Night is published serially in 1934. Wistful novel promises recur after that, but notes on movie-script assignments and dramatizations of his previous work begin to intrude by the mid-’30s. Three weeks before he died in 1940, Fitzgerald wrote class secretary Harvey Smith ’17 that his new novel was done. The Last Tycoon, of course, wasn’t close.

Along the way, bit by bit, things changed. Defensiveness begins to intrude in the notes: Gertrude Stein’s observation that he sparked a new generation with This Side of Paradise and Gatsby, and that he’ll be read when most of his contemporaries are forgotten, actually appears twice under separate secretaries. Tender Is the Night is immediately praised overshrilly as “the best thing he has written.” Then acceptance of decline begins to surface, beginning with the notice of his Esquire autobiographical article “The Crack-up” in 1936. He starts to give published interviews about his long-ago escapades and his wistful feelings for Princeton, sounding like he’s in the Old Guard; he is 40 years old.

Then, unexpectedly, there’s a blaze of light. In March of 1939, Fitzgerald writes to the secretary – for quotation – of a chance encounter with Bert Hormone ’17, the imaginary bon vivant and world traveler who acted as a 1917 talisman and in-joke (a precursor of J.D. Oznot ’68). Bert, in mid-trip from Brazil to Tahiti, has confided to Fitzgerald his bitter disappointment that his ne’er-do-well son has been turned down by an ever-more-selective Princeton. Fitzgerald commiserates, reminding Bert that his own child – his beloved daughter Scottie – also couldn’t get in, and was forced to settle for Vasser. This wonderful flight of fancy, an imaginative way to let the class know about Scottie, is a unique and simple piece of beauty. Two years later, he was dead.

Lord, Lord this man could write. The Modern Library lists Gatsby as the second-best English language novel of the 20th century (after Joyce’s Ulysses, a pretty impressive work, to be sure), but bear in mind it also lists Tender Is the Night as 28th, above such as Animal Farm and Sister Carrie. Fitzgerald could make the mundane sing: In addition to the Bert Hormone whimsy for Scottie, consider the following from a 1927 article intended simply to describe Princeton to teenagers:

In my romantic days I tried to conjure up the Princeton of Aaron Burr, Philip Freneau, James Madison and Light Horse Harry Lee, to tie on, so to speak, to the 18th century, to the history of man. But the chain parted at the Civil War, always the broken link in the continuity of American life. Colonial Princeton was, after all, a small denominational college. The Princeton I knew and belonged to grew from President McCosh’s great shadow in the ’70s, grew with the great post-bellum fortunes of New York and Philadelphia to include coaching parties and keg parties and the later American conscience and Booth Tarkington’s Triangle Club and Wilson’s cloistered plans for an educational Utopia. Bound up with it somewhere was the rise of American football.

A more succinct and evocative history lesson is impossible to imagine. His ability to feel and emote were monumental; his ability (and poor Zelda’s, of course) to live life day-to-day fitful at best. When his heart gave out over the 5-2-1 football team, his classmates understood that better than anyone. His PAW memorial (Jan. 20, 1941), one of the very best of its kind, explains:

Many of us of the Class of 1917 felt that a bright page of our youth had been torn out and crumpled up when we learned of the death of Scott Fitzgerald.

We remember that every day of his life in Princeton he was, unconsciously perhaps, laying the groundwork for the very stories which afterward brought him fame.

He continued until his death to be the gay young magician with words, still occupied with proms and debutantes, and as careless of the workaday world of middle age as in college he had been of any but his favorite studies.

The Class has lost its best known member; its first to attain nationwide fame; its first to appear in Who’s Who; and perhaps its only member who in spirit never grew much older than the college boy we all knew.

No responses yet