As a colorful cog in the virtual reach of Princeton, flinging its tiny orange and black electrons around the spacetime continuum (trying to make you think you really can’t escape Annual Giving no matter where you might hide), it behooves me to contend that you can participate fully in the life of the University at a distance, whether webbishly, glossy magazinishly, or conversationally.

Today’s item, alas, will prove this to be a crock. (Reunions probably do, too, but we’re not just talking impossibly loud cover bands in this instance, we’re looking at real higher brain function.)

You must come to Princeton before Oct. 30. Not to see the football team necessarily (hey, you have to give a new coach a couple years to find the bathroom), but certainly to visit an alignment of Princeton’s non-gridiron stars in Nassau Hall’s Faculty Room. The display is called Inner Sanctum, and it is an experience unique to the place, the genius loci, as professor emeritus Toni Morrison would say.

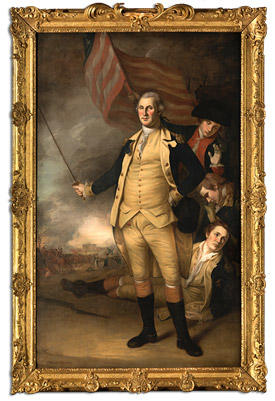

Five years or so in the making, the Art Museum project includes multiple working parts: cleaning and repair of many of the portraits (including all of Princeton’s former presidents) and the stunning woodwork details in the room, the restoration of the superhistorical frame of Charles Willson Peale’s “George Washington at the Battle of Princeton,” a history colloquium to be held this fall, a freshman seminar, and, significantly, a first-rate volume/catalog of history, reflections, and color plates capturing the room at this moment (that’s important because it will be broken up in part again on Nov. 1; Washington returns to the Art Museum, to be replaced by another Peale version).

And while Inner Sanctum is a really good book, it cannot even passingly be a substitute for being in the room, in large part because of the final element of the current upsprucing.

The room’s lighting has been redone in exquisite detail, and the result transforms drab Presbyterian ministers (redundancy alert) into what museum curator Karl Kusserow terms “household deities” in the book, and transforms great men into icons. It has to be seen to be believed and felt.

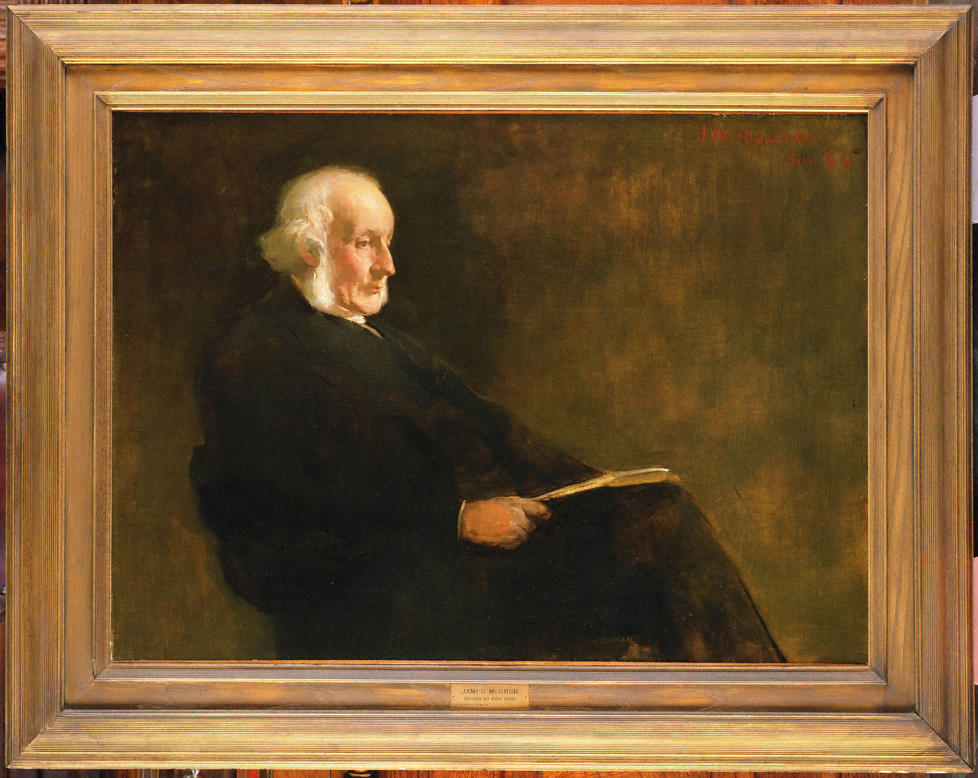

The simplest example is the most effective. Neither the largest nor the smallest of the 33 portraits in the room, that of President James McCosh on the west wall is completely typical, with a dark background and a simple pose, in his case a seated profile at some reserve from the viewer – sort of a Whistler’s Mother’s Second Cousin. Now, many of the paintings are actually rather mediocre (an important point made by Kusserow in his history text in the catalog), but this one, painted from life by the famed John White Alexander (who had studied with Whistler), is not only artistic but dominating. The new point of light on the 75-year-old face, with all else in shadow, serves the same purpose as the translucence of stained glass; it glows, breathes, demands attention. McCosh’s authority and wisdom control the entire room as they did the entire college from the day he arrived from Scotland in 1868 (“Whooo air ye, whatsyourname?”) ’til long, long after his death in 1894. He faces away from the old King George II and George Washington, and out toward the open north door and FitzRandolph Gate, imposing his ideas and ideals on his legatees. If you don’t come to the Faculty Room before Oct. 30 and visit him, he’ll know … and remember.

There is one facet to the discussion surrounding Inner Sanctum that leaves me uncomfortable, however. It has been accurately (but insistently) pointed out through the book and publicity that when the next presidential portrait is installed following the next retirement, it will represent a dramatic change: Our fine Shirley has something special that the 33 Dead White Guys, uh, don’t. OK, fine: The first woman, the first person of color – these will be highly visible on the walls of history. But what of Bill Bowen *58? He’s the first president there who was neither a Presbyterian minister nor the son of one (he’s also currently very not-dead, to be picky). If you think this unimportant, walk into the Chapel nearby and look around for a minute. And what of Harold Shapiro *64 (also not-dead)? Our first Jewish president took office only 30 years following Dirty Bicker, the all-time nadir of Princeton’s habitually low relationship with the Jewish community. There has always been substantial, radical change to be observed in the many nooks and brushstrokes here (Witherspoon’s Declaration and Madison’s Constitution are modest examples that come to mind), and always will be.

No responses yet