As we tryst again here in the high romance of virtual reality (pass the digital martinis, please), the nature of the Web and its development during the speck of time of its existence has created a unusual new problem, even for those of us with a thirst for trivia.

TMI.

Too much information is a difficulty I can’t recall facing in the age of physical libraries and engraved invitations, during which gaps in a historical tale or a biography could lead to weeks of correspondence or months of contacting repositories for nuggets of data, leading on to the next puzzle, leading on … Like The Da Vinci Code, but without the revenue.

Now we Google “orange and black plaid jackets” and come up with nine Internet citations in 0.61 seconds (of course, most relate to Tiger Band, except for the alarming “Princeton University Office of the President – Madness in March,” but that’s not the point). In this sort of superabundant environment, we easily can forget what a driving force the scarcity of information can be.

Consider: In 1908, before the democratization of personal photography, Americans mailed 678 million postcards, mostly to each other, roughly eight per person. The postage for each was a penny. The thirst for visual knowledge, not to mention details of the recipient’s sister’s trek to Niagara Falls, was unslakable.

an online display of its postcard collection

You would suspect that any ladies’ emporium that stocked such a delicate color palette might well be in danger of marginalizing its clientele, at least until coeducation 60 years later.

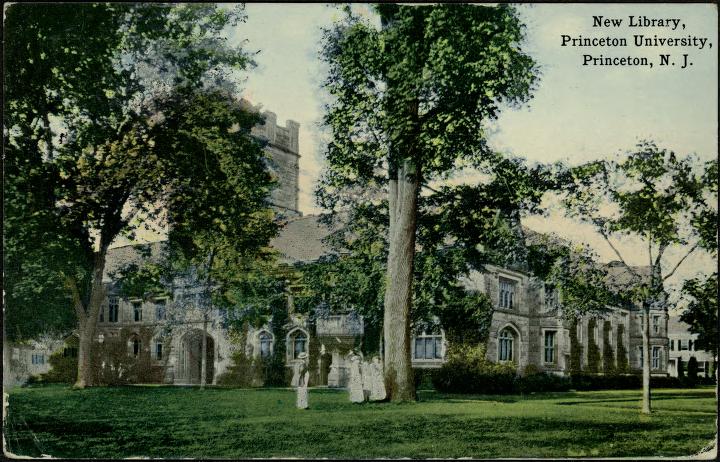

In a more substantive vein, there’s

from 1914, which doesn’t seem to resemble anything specific at Princeton until you realize the handcoloring artist assumed all gothic Princeton buildings were gray. East Pyne (the “New Library” of 1897) was and is a glorious red sandstone. Oops.

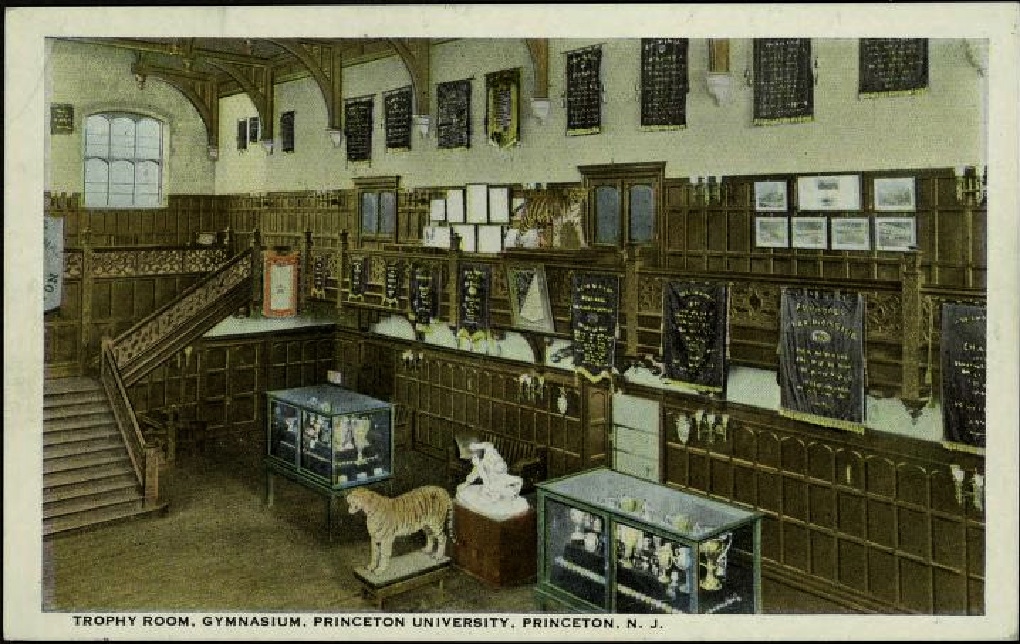

But the postcards that truly fascinate me are those that reflect a Princeton that is gone. Take for example

a view from 90 years ago that still will choke up an old Tiger letter-winner. The trophy room of University Gym, it burned to the ground in 1944, taking the vast majority of its treasures with it; the metal residue was sculpted into two modest statues by the great Joe Brown.

And speaking of fires, there’s

Historical postcards, being still plentiful and relatively inexpensive, provide a fun way for incipient collectors to get into the history game. Just last year (in my stripey guise of the Princetoniana Committee) I was contacted by Jessica Villella, a student at the Moses Brown School in Providence, kindly offering some excess Princeton postcards and cigarette premiums (cigarette premiums? A bygone marketing ploy we’ll consider at a later date) from her collection to the University. When they arrived, her package even included an original letter from Rev. Joseph Eckley 1772, an honored New England clergyman who also received an honorary doctorate from Princeton in 1793. Sure enough, three of her postcards were new to the Mudd Library collection, including the enigmatic

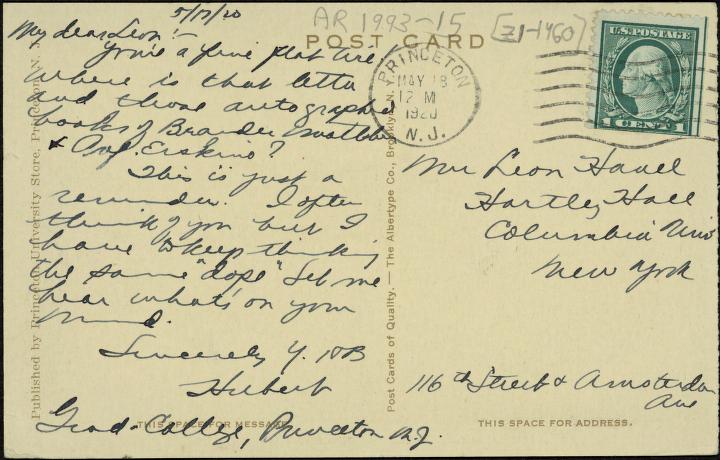

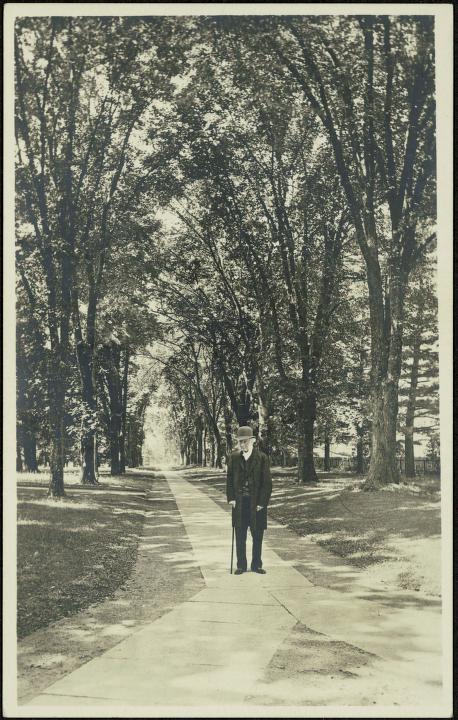

My favorite postcard, you ask?

Easy: A photo of president James McCosh on McCosh Walk (from before 1894, when he died on the 100th anniversary of Witherspoon’s death), this card dates from after 1907, showing the impact he had on the place long after his retirement in 1888. No buildings, no football players, no orange-clad chorines. One little Scotsman in a bowler hat and vest standing on the path to knowledge. Not bad symbolism for a penny.

No responses yet