Tune ev’ry harp and ev’ry voice.

Bid ev’ry care withdraw.

— Harlan Peck 1862, Old Nassau (original text)

It’s hard to find a bigger fan of Princeton’s bridge-year program than I; the opportunity to expand your understanding of the world (not to mention get a breather after homogenizing your brain in high school) and then to bring that depth to the party in college is simply a huge potential win/win/win. A large part of my enthusiasm stems from a night in June 1968; until dawn I “discussed” the world situation with a group of young East German engineers in a lounge of the foreigners’ hotel in Prague. Things were somewhat caustic (even in German, our only common language, although they all spoke fluent Russian, too), given political philosophy, Vietnam, the Iron Curtain, nuclear overkill, and such. The self-righteousness of the Germans (who supposedly liked communism a lot better than I did ’Nam) came back to mind forcefully eight weeks later, when the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia and destroyed the Prague Spring.

But my point is that this singular experience came to me courtesy of the Princeton Glee Club. The oldest formal musical group on campus, we noted it last fall as we lauded Tiger Band and the other resident instrumental ensembles, and promised to come back to ruminate on the vocal groups soon. Courtesy of our wise and magnanimous editors’ Music Issue (singing its way into your heart as we speak), here we are!

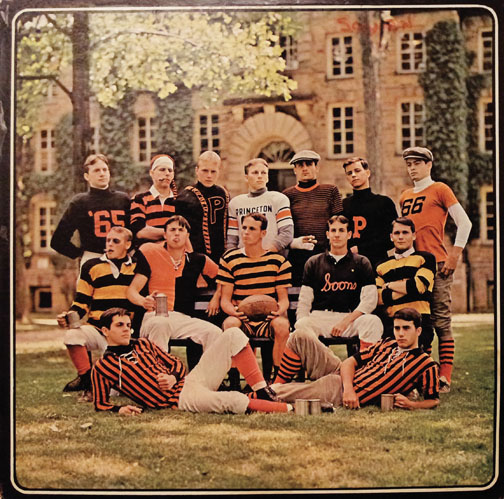

The Glee Club was the first great public gesture by the college’s master of pre-Mad Men marketing, Andrew Fleming West 1874 , while still an undergrad. He cajoled it into being through an editorial in the Nassau Lit (this was before the Prince existed) and the small ensemble began to specialize in school songs – its very first concert began with Old Nassau – and football games. It became a melodic nursery for other groups, from the mandolin and banjo clubs to Triangle to the Nassoons, over many decades. Always a big rival of its older counterparts from Yale and Harvard, it conspired with them in 1913 to sing a joint concert with each the night before the corresponding Big Three football game; that competitive tradition continues, with its 100th anniversary next fall on Yale weekend in Alexander Hall. Over the Glee Club’s huge arc of eras and repertoire, it has done everything from Stravinsky orchestral premieres to Bach to Russian folk songs and American spirituals, in locations as varied as Buenos Aires, Ljubljana, and the Met in New York.

When the College Dramatic Association threw in its thespian towel in 1891 and devoted itself to musical comedy , the Glee Club supplied musical expertise; two years later, the association renamed itself The Triangle Club in honor of its favorite song, and the rest is hystery. From Brooks Bowman ’36 to Clark Gesner ’60 to Drew Fornarola ’06, student composers (and in some cases decomposers) and alarmingly rippled kicklines have done much more than entertain Princeton and its adherents; they’ve opened startlingly wondrous views on American culture and the bizarre subtleties of the Ivy League, from its style to its Weltanschauung. Of all Princeton’s musical outlets, Triangle is arguably the most consistently creative, and certainly a potential home for those who might not always play nicely with others.

On the other end of the seriosity spectrum is the Chapel Choir, which formalized along with the great new Chapel and its new dean in 1928. It has morphed over the years from an all-male high-Episcopal model to a varied group performing the great traditional religious works and modern pieces as well in the Sunday Chapel service, and (uniquely) getting paid for it, too (a good gig for a hungry grad student). Having such an acoustic home, not to mention the great organ as a supporting player, is an experience thousands of accomplished choral singers would die for.

As the Glee Club grew in size and complexity, vocalists who wanted to stay in a lighter popular mode spun off and began a capella, five-part groups (on the Yale Whiffenpoof model); the coming-out party was the Nassoons doing Perfidia at a Glee Club concert in New Haven in 1941. They were followed in due course by the Tigertones and the Footnotes, then in the era following coeducation by the women of the Tigerlilies (later joined by the Tigressions and the Wildcats), then a real groundbreaker in the Katzenjammers – who in 1975 became the first mixed a capella group anyplace, as far as we can tell – followed by The Roaring 20 and Shere Khan . These pop music groups have been joined at various times by specialized vocal groups such as Old NasSoul (soul/R&B), Kindred Spirit (modern Christian), Koleinu (Jewish), and the Gospel Ensemble (the great tradition of African-American church music). Picking a favorite among the a capellas is not only difficult but might prove dangerous to my health (these are passionate musicians), so all I’ll say is that the Nassoons’ fabulous satire on no-loan financial aid Princeton Is Free (sung to Ashman and Menken’s Under the Sea) with its Jamaican-tinged promise, “President Tilghman, she foot de bill, mon,” is a piece of art on the Triangular plane.

Meanwhile, back in Woolworth, various student groups (like the Rock Ensemble) and composers are always prepping works for Taplin, Richardson, and other fine performing rooms on campus, and the Glee Club has put together what I would suspect to be as close to an instant Princeton tradition as we’ve seen since the Pre-Rade came along eight years ago. On the Friday of Reunions, the Club and its alumni assemble in Chancellor Green to sing Spem in Alium, a famed but rarely-heard 40-part 16th-century motet by Thomas Tallis. Sung in eight five-part choruses, it is a tour de force that more than anything resembles the great ebb and flow of the sea as it sings of God’s greatness and man’s humble state. Presented the past two years, the performance is so captivating that it will soon overflow both the rotunda balcony (where the singers form in a circle) and the floor (where listeners stand in awe). My suspicion: It’s eventually bound for the Chapel, where at the center of the cruciform nave it would offer an astounding tribute to the transcendence of Princeton and Reunions. Just listen to last year’s rendition:

Why do the decades of Glee Clubbers spend the time (this is complicated stuff) at home to learn the motet? For that matter, what drives the Tigressions and Shere Khan, the Chapel Choir and the nutjobs shaving their legs for Triangle? As far as I’ve been able to divine, vocal music groups meld the need for community with the challenge of complexity and intellectual involvement with the access to emotion that music seems to trigger in our genetic makeup. They enable the release of deep yearnings in addition to verbal artistry, the power of a family simultaneously experiencing triumph and discipline. And in their travels around the globe, they can experience other cultures while enriching their own. Whatever, it’s well worth it.

Another reason I’m so enamored of Spem in Alium is that it recalls to me a bit of another experience from the 1968 Glee Club tour, far more uplifting than the East German engineers. Our last concert was Professor Walter Nollner’s exquisite arrangement of Josquin’s mass Ave Maris Stella, performed a capella in six parts – the alto and tenor lines had identical ranges, so we split the altos (from the great Smith College Glee Club) and our tenors down the middle and sang S-A-T-A-T-B, a uniquely haunting sound – in the Cathedral at Chartres, arguably the finest example of Gothic architecture (and certainly of stained glass) on the planet.

We sang high mass, and the floor of the nave is normally bare, so they rolled out a couple hundred little wooden chairs in front of the altar, which immediately were filled and then surrounded by tourists as they entered and gathered throughout the piece. In the very front row were about a dozen little old nuns from the adjacent convent, who appeared to be in a state of torpor throughout the entire proceeding. At the end of the mass, as the last chord echoed for seconds through the stonework and off the bare floor, the entire building seemed frozen in time and utterly silent as the music evaporated; any motion would have been sacrilegious. After a beat, the little old nuns leapt up as one and began applauding wildly, causing half the choir apoplexy, not to mention the frightened tourists. This led to a back-slapping, hugging fest that could only be pulled off by the ladies of the order; had any of us tried it first, Nollner would have made us walk back to Princeton (a long way, very wet). In a troubled world, across chasms of generations, distance, and language, music provided, as it so often can, a combination of emotion and wisdom that infuriatingly eludes humanity most of the time. It is well to recall (and Princetonians have no excuse to forget) that ofttimes when we tune every harp and every voice, every care can indeed withdraw.

If 10 percent of the bridge-year students can experience half that joy, the program will have justified itself a hundred times over.

No responses yet