“When the best leader’s work is done the people say, ‘We did it ourselves!’ ”

— Laozi

While to date I’ve assiduously avoided Princeton’s current No. 1 topic, increasing clamor and the public groundswell (nothing to do with fracking, I hasten to add) compels me to face the issue head-on and make here a full, straightforward statement on the question, as controversial and upsetting as that may be.

I’m officially removing my name from the list of candidates for Princeton’s presidency.

(Pause for shock and awe.)

Given the likelihood there still remains one or possibly two viable contenders (you might wish to check the fall-term “The Law of Democracy” class website, for example), this should not amount to a full-blown tragedy, but it does necessarily cause us to look back at presidential-selection processes of the past, perhaps therefrom to learn.

Good luck with that. If the University Archives prove one thing (besides maybe that the trustees shouldn’t formally record their tavern expenditures) it’s that presidential-search committees don’t want their deliberations recorded; I suppose if the electee subsequently succeeds, nobody cares about who got him/her there, and if s/he flames out, everybody remembers. So why write it down? This leaves those of us in the history biz with a serious gap in our data, which would prevent even considering a column on the subject but for the one glaring exception that, at Princeton, always instructs the norm: time once again to recall the dogfight between president Thomas Woodrow Wilson 1879 and graduate-school dean Andrew Fleming West 1874, when the pent-up bile overflowed the minutes, the press, everything.

Simply stated, the century-ago duel to the death over the location of the Graduate College ended in a sudden burst of drama that left the University both badly divided and flat-footed. The trustees’ 1908 approval of building the new structure between 1879 Hall and Wilson’s Prospect home already was under attack by West’s forces when Isaac Wyman 1848 died on May 23, 1910, leaving reputed millions of dollars of his estate in the hands of West, who wanted the college beyond the golf course. The trustees then reversed course (no pun intended), Wilson declared his candidacy for New Jersey governor, was nominated in mid-September, and, against the pleas of the trustees, resigned flat-out on Oct. 21, before the election. Large portions of the faculty and board had chosen up sides in the grad-school battle, and the resulting sudden presidential search became something of a circus (see: Cliff, Fiscal). At the same meeting at which Wilson resigned, the trustees flailed around with an approach to interim administration, eventually deciding that Dean of the Faculty Henry Burchard Fine 1880 would run academics and that businessman/trustee John Aikman Stewart would act as the University’s first president pro tem since 1822-23 (when Philip Lindsley 1804 sat in after Ashbel Green 1783 was fired following a disastrous 10 years).

Possibly the only reason the board could even agree on that was Stewart’s status as the senior trustee, and I really mean senior: The man (who attended Columbia, although he was a Princeton parent) was 88 years old. He had been a Princeton trustee since April 1868, and thus had served through the entirety of the McCosh, Patton, and Wilson administrations; in fact, he was on the committee that welcomed McCosh when he arrived from Scotland in 1868. Prior to that, his nonvocational slate was even more hectic: He was a financial adviser to Abraham Lincoln through the Civil War. He served on the trustees’ finance committee for decades, and was still active on it in 1910; he had been at the epicenter of the endowment fight between the Wilsonians and the Westerns while remaining credible to both sides.

And, of course, at 88, he wasn’t a candidate for president. He was, however, one of the most powerful financiers in the country, having created U.S. Trust Co. in 1853 and then seen it rise along with the wealth of America to a position of international influence; he had given up its presidency after 49 years, but still was chairman of the board.

While Fine, almost certainly the most gifted administrator on campus (including Wilson and West), kept things humming on a day-to-day basis, Stewart remained at his home in Morristown, N.J., appearing infrequently at formal occasions or the rare symposium (including one in Alexander Hall with governor-elect Wilson in December 1910) and applying his signature when required. Meanwhile, the trustees were in disarray: The presidential-selection committee felt unloved (likely with cause) and behaved defensively; leaks were everywhere, and any candidate’s name caused sniping from one side or the other; after a year of this the great philanthropist and Wilson’s classmate Cleveland H. Dodge 1879 resigned in disgust from the committee and the board, despite pleading from all sides. The final straw seemed to be the presidential candidacy, outing, and refusal of Dr. John Finney 1884, a new and unaligned trustee, Princeton football hero, and one of the founders of Johns Hopkins’ medical school. After he demurred, the trustees in January 1912 received another whining report from the search committee, summarily disbanded it, then acted as a committee of the whole and – led by Finney – elected philosophy professor John Grier Hibben 1882, an ordained minister who earlier had been a fast friend of Wilson but had sided with West in the grad-college, earning deep suspicion from Wilson loyalists like Fine. The underwhelming vote was a telling 17-9.

Despite this horrendous 15-month trauma, Hibben then saved the trustees’ bacon by moving quickly and strongly to placate both sides, amazingly making the centerpiece of his inaugural address the point that “my administration must make for peace. … I represent no group or set of men, no party, no faction, no past allegiance or affiliation.” Even Fine later admitted that Hibben had been the perfect choice to bind up the wounds. Still, you certainly would think that the lessons of this fiasco would remain as painful as a battle scar for generations. So when Hibben made known his own retirement in January 1931, effective June 1932, and with the University now operating collegially again, the last thing on earth the trustees would want would be an interim presidency, right?

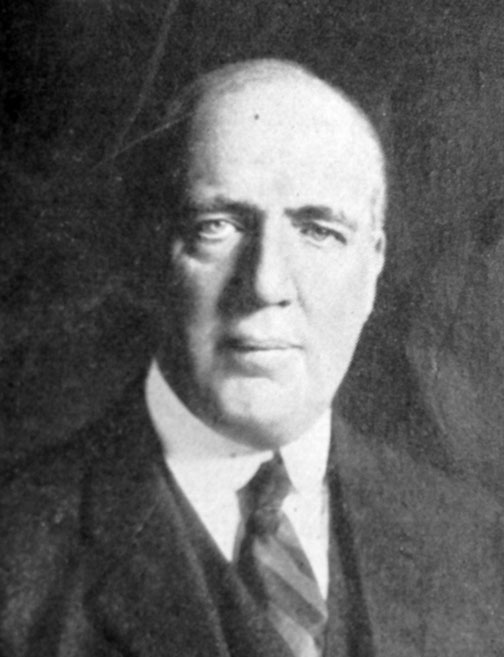

Not so much. What the trustees had learned, it turns out, was to keep a lid on their selection machinations: While speculation abounded around numerous candidates, the board was silent until April 1932 –15 months into the transition period – when they boldly named … a search committee. Huh? Whatever had gone on before, we’ll apparently never know, but when the trustees feted Hibben and his wife in June, there was no successor in sight. Senior trustee Edward Duffield 1892 took over as president pro tem, with Dean Luther Eisenhart minding the academic side. A relatively sprightly 61 years old, Duffield was the head of Prudential Insurance in Newark and came with a dizzying Princeton pedigree: a direct descendent of the first president, Jonathan Dickinson; son of a 56-year math and classics professor; Princeton parent; and younger brother of the retired 30-year University treasurer. He often was mentioned as a candidate for the Senate or (ironically) the New Jersey governorship. Far more hands-on than Aikman had been, and with an organized board, during his interim year Duffield actually built with its administrative committee a plan to restructure the nonacademic side of the college administration.

The $64 question is: Why did any of this interim activity take place? Nominated by the search committee, approved unanimously by the board and instantly taking office in June 1933 (29 months after Hibben gave notice), the new president was Harold Willis Dodds *1914, a rising faculty star who had worked with Hibben to design and build support for the new School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA), and was its first head. Immediate praise for the appointment came from such random folks as the president of Nicaragua and the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. So the full-year interregnum was for …?

- Duffield’s administrative cleanup? The elements that got implemented were modest. Dodds got his own team together quickly, and then worked fabulously well with Duffield, who became chairman of the trustees.

- Sorting through candidates? There were indeed good options, including Eisenhart, but then why was there no committee for the first 15 months?

- A cooling-off period? Hibben and Dodds worked well together, and the vast majority of Hibben’s team stayed on in the new administration. What’s to cool?

If there was a reason, it remains undocumented, and thus mystifying. Perhaps the truth lies in further lessons learned, exhibited in the ensuing four presidential searches prior to the current one: Since June 3, 1933, Princeton has not seen a single day of an interim president, and won’t this time either.

And just remember, when that portentous announcement is made this spring and it turns out not to be me, now you know why, and you heard it here first.

No responses yet