Here’s to Woodrow, King Divine;

He rules the place along with Fine.

We fear that soon he’ll leave this town

To try for Teddy Roosevelt’s crown.

— The Faculty Song

So there I am, standing on the edge of Cannon Green (rallying as of yore) for a bonfire on the Saturday night after we’ve lost to Dartmouth – an inane scheduling idea that we won’t delve into further now – and soaking up the atmosphere. The current crop of otherwise careerist undergrads seems to be truly involved, a very nice sign in an increasingly mechanistic world (said the guy with the podcast), and Tiger Band is tooting up a storm in preparation for the festivities.

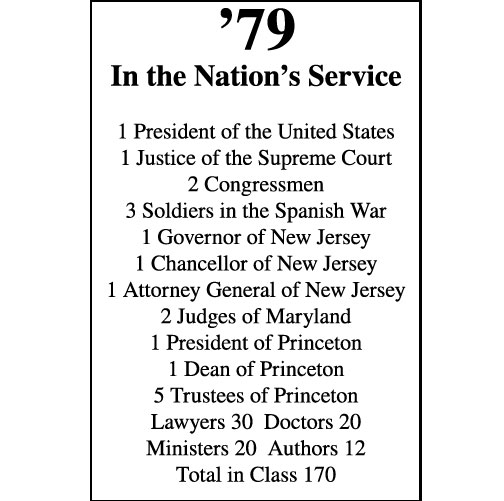

The banner of this year’s Class of 2013 seniors hangs on the south side of the Nassau Hall faculty room, and on the railing of West College (nice historic touch) are the black and orange banners of the most recent eight senior classes to have a Big Three bonfire, from 2007 back to 1967. But in the middle of them, there’s a smaller white banner, which reads as follows:

Yes indeed, Princeton’s very first Big Three championship was in November 1878, and T. Woodrow Wilson 1879 (who to be scrupulous is actually five of the people cited on the banner) and his obviously non-shy senior classmates were there to drink it in; “Tommy” Wilson, in fact, was secretary of the Football Association (although his own sport was baseball). On campus in the middle of the Rev. James McCosh’s transformative tenure as president, the class became part of the core of aggressive alumni who, between their graduation and World War I, turned their college into a university that would be unrecognizable even to McCosh.

As we celebrate the centennial of Wilson’s inauguration as U.S. president on March 4, it’s intriguing to consider these movers and shakers and their high-profile effect on Princeton, not to mention upon their afore- (a-five?) mentioned champion, and to try to understand the part they played in his academic ascendance, Princeton presidency, and eventual lightning strike into global politics.

For starters, we should consider The Grand Gesture, at which they excelled. Just so nobody would forget them, on graduation the members of the Class of 1879 donated two sculpted lions (sic) for the front steps of Nassau Hall. Within 10 years, with the entire country calling the football team Tigers, that became problematic, so they in 1911 donated the current (and far finer bronze) Nassau Hall tigers that your daughter poses on at Reunions, with their class numerals on the front. In 1896, they commissioned a stunning relief statue of the late McCosh from the great Augustus Saint-Gaudens for the Marquand Chapel. When that was destroyed in the 1920 fire, they simply commissioned from the artist’s estate a (very expensive) copy, which now graces the Marquand Transept of the new Chapel. In the interim, they really got rolling, recognizing Wilson’s election as Princeton president in 1902 with a sparkling gothic dormitory on Washington Road – modestly named Seventy-Nine Hall – at their 25th reunion two years later. It includes over its archway a custom-designed office for their classmate, paneled in tiger maple (duh) and with a huge fireplace, over which is hugely carved Ex Amore Magno Donum Parvum, uncannily paraphrased five decades later by Lennon and McCartney: “I get by with a little help from my friends.” Inside the ’79 arch below – in bronze, of course – are the names of the 170 classmates noted on the banner. Parvum, indeed.

And how did this high-profile support group see Wilson’s rise? Well, for starters, they threw him a huge testimonial dinner at the Princeton Inn with an engraved program listing all his publications … in 1897, following his “Princeton in the Nation’s Service” address but five years before he became University president; he was 40. Then, lucky for them, Your Favorite Periodical entered its own feisty infancy – PAW began in 1900 – and so was jolly well on the spot to let the loyal men and true of 1879 vent. And they really did …

Now, Wilson was a famed orator even then, but the class secretary and the Notes editor (who in those days actually did the writing) tended to overplay to their strength: Between the magazine’s debut in April 1900 and June 1902, when he suddenly became University president, Wilson is noted in the “Alumni” section 18 times. He’s writing – for the Atlantic Monthly on “Reconstruction in the South,” again on “Democracy and Efficiency”; for Harper’s, the first chapters of his A History of the American People. He’s elected vice president of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. And he’s speaking – my heavens, how he’s speaking: on “The Great Leaders of Political Thought,” on “What it Means to be an American,” on the 125th anniversary of the Battle of Trenton, on “Americanism.” He is everywhere (before the Wright brothers, remember), a veritable Cornel West *80 of his time: Lawrenceville, Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore, Union County, Vassar, St. Louis, Chicago, Indianapolis, and Northfield, Mass. The accolades pour in: The Princeton Club of Chicago holds a testimonial for him (still just a professor, remember), described as a “beefsteak dinner and Princeton love feast.” The Baltimore News describes him as “a man who possessed that rare personal quality to the sway of which men in all ages have delighted to bow.” A letter to the Indianapolis News says he should be president … of the country. In June 1902 he does become the president, but of Princeton, and moves from Class Notes onto the PAW news pages.

Eight years later (after the Grad College slugfest with Andrew Fleming West 1874), Wilson resigns as president to run for governor of New Jersey, and during the interregnum between presidencies again assaults PAW’s alumni section, with a vengeance. A week before taking office in Trenton on Jan. 17, 1911, he is in St. Louis to preside over the renamed American Political Science Association and for another gala luncheon with the St. Louis Princeton Club. A week afterward, he is reading from his writings for charity at the Waldorf in New York. Nine months later (after numerous political engagements throughout the Garden State), he is Chris Christie-ing a week in Texas and Wisconsin; then another foray in Oregon. Before year’s end there is a “Woodrow Wilson Club” at Princeton and indeed a “Woodrow Wilson League of College Men” throughout the country working for his presidential nomination. At the beginning of 1912 he’s in high gear, speaking in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Frankfort (Ky.), Chicago, Kansas, Des Moines, Columbia University, Boston (a speech and full torchlight parade), Worcester, Harvard, Atlanta, Jacksonville, Savannah, the NYC Reform Club – and that’s all before June 1.

His still-cited reformist efforts in New Jersey were substantial, but when he actually stopped by to do them is something of a mystery. In any case, he was nominated for president on Sept. 25, 1912, and after 617 days as governor was well on the way to the White House, courtesy of Teddy Roosevelt’s intrusion into the race opposing his chosen successor, William Howard Taft, in the only HYP Big Three presidential contest to date.

It’s surprising the Class of 1879 didn’t commission another banner to mark the occasion. They did throw a huge class dinner for Wilson at the University Club in New York the week after his election in November, then another the night of his inauguration at the Shoreham in Washington on March 4, 1913 (he was there, having canceled the Inaugural Ball as too frivolous). Then Wilson again passed out of PAW’s alumni section and back to the nation’s front pages.

His class didn’t even get to do their own memorial when their worshipped compatriot, whose health never was the best to begin with, finally succumbed to the pressures of the entire unsatisfied world in 1924. The PAW editors expropriated the duty, although two of his classmates were among the six who wrote a full-page testimonial on behalf of the entire alumni body. It reveals that many of his specific accomplishments – the preceptorial system, the Federal Reserve, even the failed Treaty of Versailles –already were recognized as transformative. But it actually comes nearest the truth in its summation: “History will count President Wilson among those supreme idealists who had the power of doing great practical things.”

Although I suspect the one heartfelt sentence included by his non-shy compatriots of the Class of 1879 as they recalled his tiger maple office, the bronze tigers (today known as “Woodrow” and “Wilson”), Seventy-Nine Hall, and the class banner, was this: “As a teacher he was unsurpassed.”

Ex amore magno donum parvum.

No responses yet