I yam what I yam and that's all what I yam.

— Popeye the Sailor, 1933

Life’s not worth a damn ’til you can say “Hey world, I am what I am!”

— Albin Mougeotte, La Cage aux Folles, 1983

We spend our quality time here, for the most part, considering the University vis-a-vis the large questions of times past and times to come. “Princeton in the nation’s service.” Dark energy. How did Shakespeare do that, anyway? Genomics. Starving populations. The Princeton offense. Global warming. We give short shrift, sometimes to our detriment, to the more mundane aspects of daily slogging that, while humble, still make up a significant portion of the genius loci that the good professor emeritus Toni Morrison talks about as Princeton’s great strength. In today’s example, we consider the metaphysical import of being a landlord.

Supplying shelter for more than 6,000 people can be, depending on the day, the weather, and your viewpoint, something ranging from a challenge to an odious curse from hell (and hardly cheap). But at the same time, it is one of the cornerstones (literally, in this instance) of the idea aggressively pursued by all of Princeton’s administrations throughout the 20th century, that living 24/7 in the community is qualitatively superior to wandering by for classes and a beer. And in our vast universe of Unintended Consequences, it also generates a subtle complication (even beyond room draw – shudder). It provides the University with a reason to care who sleeps with whom.

Here in virtuality, we have the good sense to slap a TMI label on such questions and move on, but a landlord really can’t, at least completely. And so Princeton, the institutional flower of the Great Awakening and dour New Light Presbyterianism, inevitably found itself in the sex business.

Any historical review of the dean’s dorm-visiting rules, in today’s world, takes you closer to the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party than to Nassau Hall (aka Dorm No. 1). There was, for example, some real institutional pride in the 1930s and ’40s because Princetonians were too mature to be insulted with the Puritanical stigmata of Harvard, where a female chaperone always was required when an undergrad entertained a woman in his room. (Yes, that’s right, codified FFM threesomes, but let’s move on …) At mature Princeton, you could entertain a Lady (it would most certainly be a Lady with a capital “L”, of course) any way you wished … until 6 p.m. The rule was memorialized as Sex after Six. From there, we could go on recalling the perils of parietals, as women’s visiting rules were known, debated, and vilified, but it’s just too demeaning: The administration fought the students, the trustees undercut the administration, deadlines became different on different nights, in different buildings; it was chaos. And in the great tradition of Prohibition, nobody paid attention. One memorable 5:25 a.m. fire in Patton Hall in the ’60s spilled half as many forbidden women onto the lawn as students (the landlord was not pleased).

And that only covers the legal straight sex. Gay sexual activity still was technically illegal in New Jersey until 1978. Thus, the history of the LGBT (lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender) community at Princeton resembles that of the group elsewhere in Western culture since the Middle Ages – nobody knows much with any precision, except that perhaps 5 to 10 percent of the men and 3 to 6 percent of the women were involved. The fact that no one officially could acknowledge it – and that included the potential regulators as well as regulatees – made the whole underground situation an enigma, on a good day. Meanwhile, of course, the outside “culture’s” biases against non-heterosexuals – the pathetic basis of which we’ll leave to Freud and the other pros – simply served to exacerbate everything; campus hooligans periodically harassed folks they didn’t like with homophobic epithets, and so everything went farther underground.

This information vacuum undoubtedly complicated the University’s planning for this month’s conference for LGBTA alums, entitled “Every Voice,” on a few levels. (Not to mention divining what the current accurate acronym for the entire non-heterosexual community might be – the “A” is for ally; one option, believe it or not, is LGBTQIA+). While the Fund for Reunion/BTGALA (FFR), Princeton’s gay-alumni organization, has been running and increasingly well-supported since 1986, a wide range of potential conference attendees have never been active with the group, many were never out while on campus, and some aren’t even today. And of course, the University has little record of any of this, as it did have when it organized the black alumni and women alumnae conferences of recent years (both wildly successful, by the way). It would, in fact, have been a convenient excuse to avoid an LGBTA conference altogether, but to everyone’s credit, that didn’t happen. Currently rated on most lists as one of the most welcoming of colleges to LGBTA students, Princeton persevered and publicized the conference to the point that nearly 400 alumni and guests are pre-registered, which in part shows not only the LGBT alumni activity and the long-standing mutual support available on campus, but also the general camaraderie that comes from living with and knowing the folks in your own dorm.

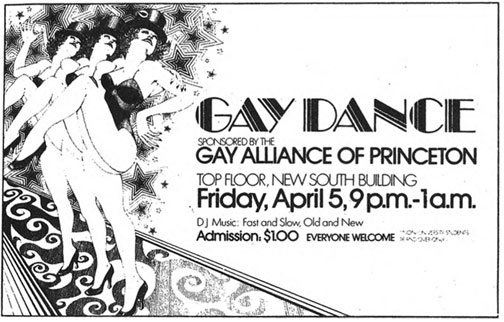

Believe it or not, that general approach goes back over a century, to the fortuitous day in 1910 when Stewart Paton 1886 created from scratch the first college mental-health program in the country to complement the excellent medical services spearheaded by Isabella McCosh and memorialized in the first infirmary, named for her, in 1892. It has grown with the student body to offer a wide range of services for LGBT students, faculty, and employees. Meanwhile, the students themselves began to organize only three years after the Stonewall riots in New York: In 1972, the Gay Alliance of Princeton formed, initially to provide mutual support and hold a dance every couple months. By 1980, the Women’s Studies program began, including gender studies courses. The Women’s Center, already a decade old, hosted periodic social events for lesbians, and by 1982 the Gay Women of Princeton were operating separately from the GAP. In 1985, the University added sexual orientation to its nondiscrimination policy. The alumni were next; as the AIDS crisis began to surface, and seeking to support the undergraduate groups as well as create a comfort zone for gay alums, the Fund for Reunion was organized in 1986. With grad students, bisexuals, employees, and others beginning to form groups as well, the dean of the chapel in 1989 began to fund grad students part-time to organize and coordinate the various LGBT service and social programs, and this eventually grew into the current LGBT Center. The first Pride weekend (now a week each year) was held in 1992, the various undergrad LGBT groups consolidated and became the Pride Alliance in 1999, the lavender graduation ceremony began in 2002, then academically the Program in the Study of Women and Gender changed its name to the Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies in 2011 to mirror the changing scholarship in the field. Well-supported by both the University and FFR, the LGBT Center has had a home in Frist Campus Center with other student groups since 2006, and is doubtless a key in Princeton’s widespread reputation as a welcoming place.

Which of course is what it should be, notwithstanding that bulwark of democracy, free speech by the periodic dissenter (see: global warming, above). It may be perplexing to those who know the University only by its Gatsbyesque stereotype or by its prior historical resistance to Jews, blacks, women, and other minorities; who would guess (anachronistically) that the Other, in the form of an LGBTA individual, would not be a welcome persona in a tight-knit community like ours. Well, there’s actually an obvious reason that’s not true, which could serve as a consideration for many LGBTA issues in the broader culture: These folks are not the Other, and never have been; they are our friends, roommates, and fellow scholars, whether we are 20 years old or 70; we know them and they know us; we often knew they were gay (whether they did or not) or simply didn’t care. And the landlord doesn’t care either; we’re Princetonians.

We are what we are.

No responses yet