“The essential is to excite the spectators.

If that means playing Hamlet on a flying trapeze or in an aquarium, you do it.”

— Orson Welles

My wonderful friend Jim Robinson ’43 died this past May. One of those thousands who had their Princeton years interrupted by World War II and so was taught their true value as little else possibly could, he was a lifelong techie (let’s face it, mechanical engineers – and many other engineers – are actually techies or techettes in a sport jacket) who gloried in the wonders of the physical world. He also has a unique claim to fame even within the pocket-protector mafia: While an undergraduate, he was WPRB’s first technical director. As the station moved around from Pyne Hall to 1903 Hall to its fateful submergence into the basement of 11th entry Holder (the library’s dead-storage area had abandoned the space, because it flooded in any substantial rain), he nursed the station into being, then benevolently kept his eye on it for 70 years as a station trustee and honored elder statesman. I’ve written about dozens of kind, generous Princetonians, but I believe Jim was the kindest, most generous there was.

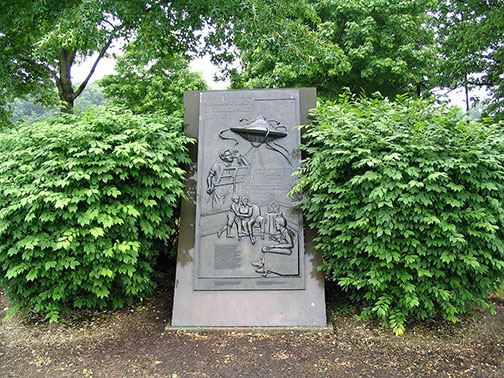

I’m not going to tell the story of WPRB today; that will wait for a couple years and the station’s 75th anniversary. But in fondly recalling Jim and the cultural atmosphere in which the eager undergrads went about creating live radio at the end of the Depression, we need to consider another broadcast episode in Princeton’s history whose 75th takes place this Oct. 30: the tale of Grover’s Mill’s 58 minutes of fame, and the esteemed Professor Richard Pierson, likely the most famous imaginary Princeton faculty member of all time.

If you cross Route 1 to Princeton Junction, then turn left into the woods, Grover’s Mill, N.J. (most of which is a pond), lies precisely four miles from the front door of Nassau Hall. If Professor Pierson lived in an imaginary faculty house on Broadmead or someplace nearby, he was even closer. This made it very convenient for him to hop over and guide the terrified imaginary populace of the United States through the highlights and sidelights of the invasion from Mars.

For Professor Pierson was portrayed by the 23-year-old Orson Welles, and in concert with his merry band of the Mercury Theater, he was bringing the listeners to the CBS Radio Network a Halloween treat, a dramatization of H.G. Wells’ 40-year-old novel, The War of the Worlds. It was promoted in newspapers beforehand; it was described as a drama at the head of the show; Professor Pierson’s ominous preamble clearly sets it in 1939, a year in the future. Welles always said that audience panic (never mind an FCC investigation) was the farthest thing from his intention, and the facts bear him out. But two people working in odd coincidence conspired to panic a few million souls (and a disproportionate number in New Jersey) – the brilliant young Mercury scriptwriter Howard Koch and the booker on Edgar Bergen’s show over on NBC. Bergen, who had been on the air about a year with his hench-dummy Charlie McCarthy (you, the Discerning Historian, will need to explain to me sometime the allure of a radio ventriloquist), dominated the 8 p.m. Sunday airwaves, but on Oct. 30, 1938, his lead-off guest was lame and so a significant batch of his fans started channel surfing (anachronism alert) over to their local CBS station and ran into War of the Worlds – after the disclaimer and preamble were long gone. There they found themselves amid urgent news bulletins, enmeshed in the heat rays and carnage of the fearsome metal machines from outer space shrugging aside the most modern human armament technology. (The entire work can be interpreted, on one level, as a fable about the futility of the machine age.) Filtered through the pen of Koch and his 24-year-old assistant, Anne Froelick – a Princeton townie – this horror had been transplanted from Wells’ English countryside of 1900 to the current American East Coast megalopolis (anachronism redux) in a remote spot that was readily accessible to both the government capitol of Washington and the media capital of New York – Grover’s Mill.

The contiguity of Princeton was perfect to lend credence to the script; not only was Einstein in town with his brainy buddies at the Institute, but the University had a long and distinguished tradition in astronomy. It began in 1840 with Stephen Alexander, who nursed the discipline into the academic mainstream, then succeeded in building the Halsted Observatory on campus (where Campbell Hall now sits) in 1872. Halsted in turn drew the great Charles “Twinkle” Young to follow Alexander in 1877, training an entire generation of astronomers before his retirement in 1905. In 1912, Young’s student, Henry Norris Russell 1897 *1900, took over for an astonishing 35-year run and many global honors, and built FitzRandolph Observatory east of Palmer Stadium. Russell was succeeded in turn in 1947 by his student Lyman Spitzer *38, one of the most decorated astrophysicists of the 20th century, namesake of NASA’s Spitzer space probe. Spitzer, while simultaneously setting up the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab and constructing Peyton Hall on the side, ran the astrophysics department until 1979, completing a remarkable century under three teacher/student legatees.

So Professor Pierson’s pedigree as the huffy (he first dismissively describes the chances of life on Mars as “one in a thousand”) space expert on War of the Worlds had instant viability, and when he started describing the icky Martians and their diabolical weapons at Grover’s Mill, the realistic on-the-spot-news tone of the broadcast was pitch-perfect. Complete with fictional intrepid radio news reporter Carl Phillips (who, alas, becomes a toasted casualty of the heat-ray attacks), Pierson holds the audience taut for a full 39 minutes “on the scene” as the Martians utterly dominate all military forces before a program pause brings the story back to ground. After the break (in which it again was made clear this was a drama), Pierson/Welles tells the rest of the tale, wherein the Martians are miraculously felled … but only by microscopic earth bacteria, to which they have no immunity. At the very close of the broadcast, Welles breaks character and wishes the audience a happy Halloween, saying the drama has been Mercury’s way “of dressing up in a sheet, jumping out of a bush and saying, ‘Boo!’ ”

Of course that was a bit late – in the real world – for those who were out in their cars fleeing the East Coast, or burying police switchboards, or being interrupted in church by announcements of the apocalypse. Naturally enough, as panic-stricken as the folks in San Diego and Washington were, the locals around Trenton were a lot more so, and in a bizarre case of life imitating art, out went the esteemed head of Princeton’s geology department, Professor Arthur Buddington, and his go-getter pal, Professor Harry Hess *32 (later the creator of tectonic plate theory), with their seismic instruments and intrepid students to Grover’s Mill to investigate the “meteor landing.” What they found was a bunch of clueless gawkers, trying in vain to find the meteor, too. Meanwhile, dozens of confused students got frightened calls from mom, who needed reassurance Martians hadn’t eaten little Snookums and his roommates, and the Prince editors fielded all sorts of alarmed alumni and student questions on the phone.

A stunned Orson Welles faced the (spooky) music the following day in New York. A controlled riot of a press conference , besides repeated insistence that the whole thing was unintentional and they were sorry (CBS had, after all, preapproved every word of the script), really yielded but one statement: “I don’t think that we shall choose anything like this again.” Juniors Dago Springs ’40 and Bob McBride ’40 of the Prince got an exclusive interview with Welles, who clearly understood what Tigertown had been put through thanks to the efforts of Professor Pierson. “It seems to me that Princeton, focal point of the attack,” he told them, “was calmer than most of the rest of the nation. As for the poor farmer of Grover’s Mill, whose field was trampled under by fleeing Jerseyites – he has my profoundest sympathy. His farm was chosen by purest chance as the locale of the ill-fated dramatic broadcast.”

The New York Times editorial board (certainly none of whom were 23 years old) harrumphed, “Radio is new, but it has adult responsibilities.” The FCC sheepishly came to the realization that nobody had done anything remotely illegal. PAW’s undergrad On the Campus columnist Fred Fox ’39 – yes, believe it or not – reported a group of enterprising students had formed the League for Interplanetary Defense, complete with theme song “Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys are Martian.” Over at SPIA (now the Woodrow Wilson School), Associate Professor of Psychology Hadley Cantril already was running the Princeton Radio Research Project; he expanded its scope to include this serendipitous mental experiment, and a year later published The Invasion from Mars, a Study in the Psychology of Panic, a groundbreaking tome in mass communication and group behavior that remains in print to this day.

Although we live in a far more cynical age now, you know intuitively that no television program or David Lean epic film could ever have accomplished what the youngsters of the Mercury Theater did in 1938; any physical image attached to the artful play instantly would have revealed it as well-produced fiction. But the abiding power of radio – those of us who grew up immersed in it proudly refer to the medium as the theater of the mind – is to let the listener expand its truth as far as she can take it, even up to the 34 million miles between Earth and Mars. And obviously, millions of Americans in 1938 did just that. Jim Robinson and his buddies, just a few years younger than Welles, knew this too, and thought that the students should join in the broadcast action – after all, at its very worst, spinning jazz and swing records out into the ether was more fulfilling than slogging through Grover’s Mill with your geology professor searching for Martians.

No responses yet