Sanctions had an effect, but sanctions didn’t save South Africa. South Africans saved South Africa.

— Bill Keller, TheNew York Times

Having had decades to consider apartheid while the noose of economic sanctions from much of the rest of the world closed – maddeningly slowly – on South Africa, I suspect that the most despicable part of such a despicable system was the simple cynicism of the whole thing. Although it had early roots in the sense of manifest destiny of white Afrikaners, after its ascendance no supporter of apartheid ever seemed to claim the moral high ground, to even bother to invent some fairy tale whereby the blacks and coloreds being exploited were somehow better off than they would be under a pure democracy, just that they were somehow simple, clueless folk who couldn’t be trusted with full rights and responsibilities. This was ludicrously against the tide of history; the National Party of South Africa began to construct its restrictive laws in 1948, for example, simultaneous to Harry Truman’s desegregation of the U.S. military. Apartheid was just a power grab, plain and simple, by a bunch of thugs whose main upside in the harsh light of history likely will be that they weren’t Hitler or Pol Pot.

So much for the sermon; if that’s all I had to add to the emotions surrounding the death – peacefully of old age, at home, unlike Mahatma Gandhi or Dr. Martin Luther King – of the iconic Nelson Mandela, you can bet your stripes I wouldn’t be accosting you here. Fortunately – aw heck, miraculously – there’s another, highly instructive side to the hideous blot of apartheid.

It begins even before the unconscionable suffering of Mandela (he was imprisoned in 1963), via the truly global efforts to ostracize the South African apartheid regime and force it to admit its moral bankruptcy via real bankruptcy – economic sanctions. And that’s where the U.S. campuses come in. Amazingly, given our dearth of minorities at the time, the issue arose at Princeton as early as 1957, when Methodist and Anglican clerics from Africa began to speak against the 10-year-old system whose restrictions still were being designed and implemented. In the ’60s, many more black students matriculated at Princeton, and as the U.S. civil-rights, Vietnam, and IDA causes arose, they often were conjoined with apartheid in public demonstrations of various sorts. The most notable of apartheid-focused actions was the – quite civil, actually – takeover of New South in March 1969 by the recently formed Association of Black Collegians, which urged the University to divest of holdings in companies doing business in South Africa; an ad hoc faculty advisory committee chaired by Professor Burton Malkiel *64 earlier had come out against the idea as ineffective.

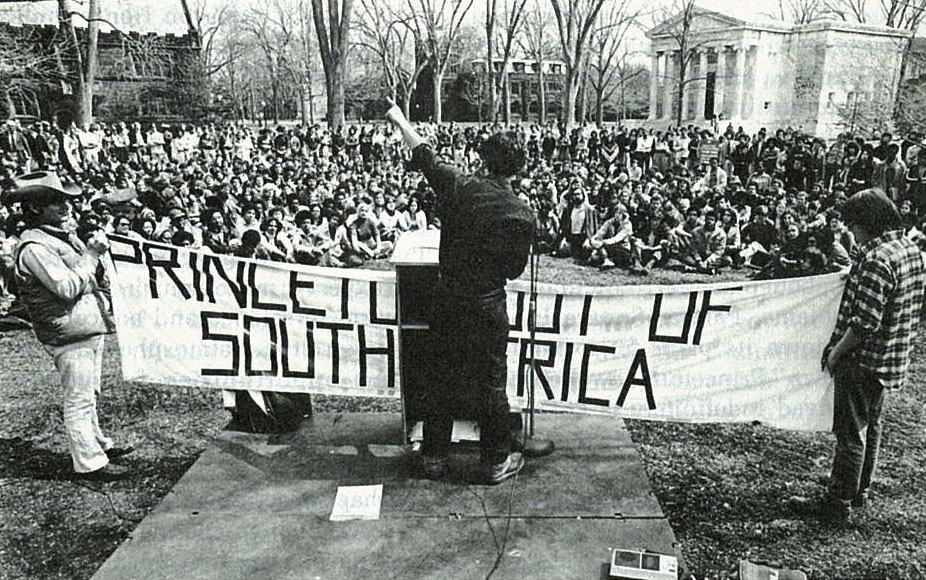

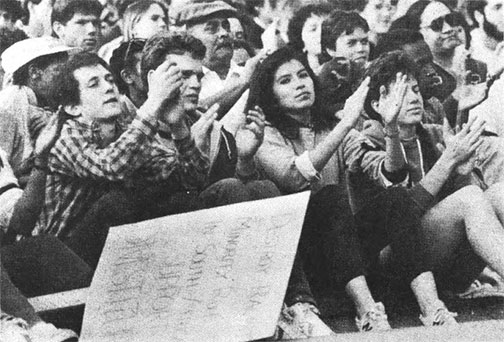

As the issue festered, and the trustees periodically reconsidered and rejected divestiture, the cause recurred on the world stage. In 1977 the Sullivan Principles were developed as a weapon of corporate efforts to blunt or eradicate apartheid and similar social unjustness, and the concepts of responsible investing began to develop. Subsequently many campuses, including Princeton, had their largest demonstrations in years in 1978, almost entirely focused on apartheid. This resulted in an explicit policy statement by the trustees, essentially saying that they gladly would take positions as shareholders to combat apartheid, but not really addressing divestment directly. A series of crackdowns in South Africa resulted in much the same campus reaction in 1985, this time including a Rev. Jesse Jackson-led rally that drew more than 2,500 demonstrators, probably a high-water mark at Princeton since the ’60s, followed by the arrest of 80 protesters for blockading Nassau Hall. At Columbia, the trustees did indeed decide to completely divest; the Princeton trustees tightened their standards and liquidated four holdings over the next eight years, based primarily on the Sullivan criteria. And ever so slowly, under world pressure, the economy of South Africa slowed to a crawl.

So it was that, after 21 years, there still were active Princeton protesters on the day in February 1990 that Nelson Mandela was released from Robben Island. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the anti-apartheid movement on campuses was simply its duration; in a microcosm where a generation is four years, there has rarely if ever been student activism around another external cause extending across three decades. There was a visceral feeling somehow that, despite a distance of several thousand miles, this was important, perhaps a reaction to the obnoxious bullies in the government, perhaps a legacy not only of Dr. King’s memory but of reparation for America’s (and Princeton’s?) inglorious track record of race relations. In any case, it was serious and – remarkably for student idealism – it had a material effect. Mandela was released to worldwide adulation, negotiated transition of power over an arduous four years, and was elected president of South Africa in 1994.

As important and instructive as the demonstrations and the boycott/embargo were, they only set the stage, after the final dissolution of the apartheid regime, for the truly transcendent element of the morality play. When apartheid died, it could have led to bloodbaths, dissolution, or utter chaos. Instead, it led to Nelson Mandela’s finest hour.

Media operations being my thing, I have across the years found myself in some fascinating places, working with fascinating people. Among the least likely and most important were the folks at the South African Broadcasting Co. in 1997. The pervasive national broadcaster recently had been overhauled, changed from a propaganda mouthpiece of the old white regime to a sort of public-spirited BBC model trying to find its way. As they reimagined themselves and tried to catch up with global industry standards, the SABC newspeople each Sunday would produce an hourlong summary of the week’s mesmerizing events in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings. If you don’t know about the TRC, I strongly suggest you read up on it, because it is a glowing beacon at the very end of the foggy gloom of the 20th century, but its extraordinary concept – principally the creation of Mandela – was simple: People did terrible things underapartheid that needed to be exposed and remembered; if you publicly admit what you did, you wouldn’t be punished for it. Forgive, but never forget.

Watching the many pages of daily South African newspaper TRC revelations and the weekly TV shows, as heinous abominations were spread daily in front of such wise TRC panelists as Bishop Desmond Tutu, was like seeing the Watergate hearings restaged with murderers substituted for the burglars – intense, wrenching drama impossible to predict or recreate. Meanwhile, the overarching logic of the situation compelled – utterly demanded – deep self-examination. Which model do you believe in: the Nuremburg trials or the TRC? Executions or forgiveness? Vengeance or reconciliation? What, in the end, is justice really, not only in the law books but in our hearts and minds?

I have severe doubts that the TRC approach would ever go over big in the United States – we felt just and merciful allowing Rudolf Hess to die in Spandau, rather than killing him outright; somehow letting him go free simply for admitting his complicity with Hitler wouldn’t poll well for any American politician desiring re-election.

This brings us around again, somewhat surprisingly, to this year’s Freshman Pre-read and Professor Kwame Anthony Appiah’s examination of honor practices, and asks us whether the same sense of morality that caused so many Princetonians to add their voices to the economic shunning of apartheid over more than 30 years would extend to pardoning those who perpetrated it, all in the name of a long-term civil society and a more ethical world. Dr. King and Gandhi might agree; but there are few Mandelas, Kings, and Gandhis among us now, not that there ever have been many. Do we live in the same honor world with them? We thought we did in 1957, in 1969, in 1978, in 1985, in 1990. Did we really? Can we now?

No responses yet