All I know I learned from telly -

What to think and what to buy.

I was pretty smart already,

But now I’m really, really smart - very very smart.

Endless content, endless channels ...

Endless chat on endless panels ...

All you need to fill your muffin,

Without having to really think or nothing!

— Mr. Wormwood, Matilda

So there I was, hanging on the opening words of the third episode of the new TV series Cosmos, with our postdoc-gone-Hollywood Neil deGrasse Tyson channeling the late Carl Sagan, and he’s suddenly echoing what has been nagging me for weeks: the unique facet of humanity that is the longing for pattern recognition. In my case, it’s been the athletics department bouncing around in my brain; while my task here is ostensibly to unfurl the history of our fair Alma Mater generally, and indeed we’ve recently delved into such intellectually earnest fields as philosophy, math, computer science, fine arts, the Library, and the Nude Olympics, somehow every time I turned around some historic outcropping of the jock world presented itself.

We most recently re-examined the rescue of March Madness for the NCAA by Pete Carril and his 1989 cagers in the Georgetown game 25 years ago. Last fall we discussed the almost impossible-to-believe-even-in-retrospect talents of Hobey Baker 1914 on the 100th anniversary of his last skate for the national-champion Tigers. It’s 50 years since the most recent undefeated football team of 1964, and coach Dick Colman’s triumph via lessons learned from his late mentor, Charlie Caldwell ’25. The very first Princeton intercollegiate athletic event was 150 years back: The baseball team lost a 27-16 pitchers’ battle to Williams on Nov. 22, 1864. One of the best of Princeton’s 20 national-champion football teams of the 19th century was 1889; the team was unique in being the only one captained by one of the five Poe brothers, Edgar Allan Poe 1891 (no, his nephew). Juicy historical vignettes kept incessantly popping up, clamoring for attention.

But wait, you say – in honor of Dr. Tyson and his patterns – wait: What about 1939? Well, Ardent Historian, that’s the tale of Billy Moore ’39, Dan Carmichael ’41, Stan Pearson ’41, and their brush with immortality.

Of course, 1939 was hardly your run-of-the-mill year. Everywhere in the real world, things were going to hell in a handbasket. Besides the Germans and Soviets looming over Europe and the Japanese Empire gobbling chunks of Asia, an instant replay of the Great Depression created a sense of doom that bled into the newspapers and the public psyche. So, unsurprisingly, the most vibrant populist corner of the unreal world was thriving as never before … or perhaps even since. Nominees for various Oscars in 1939 included: Of Mice and Men, The Wizard of Oz, Stagecoach, Wuthering Heights, Gone With the Wind, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Gunga Din, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, Dark Victory, Ninotchka, Goodbye Mr. Chips, The Four Feathers, Beau Geste, Only Angels Have Wings, Union Pacific, Drums Along the Mohawk, and Young Mr. Lincoln; triple the number of fine films in even an exceptional year. It was the desperate, golden age of escapism.

And radio, not to be outdone, continued to entrance and/or distract the living rooms of America. The Theater of the Mind dusted itself off after the kerfuffle of The War of the Worlds in Princeton at the end of 1938, and the following year hit new records of saturation: Three-quarters of the homes in the country now had a set, against only a third back in 1930. NBC’s powerful Red network ruled the national airwaves, and its top two shows – Edgar Bergen & Charlie McCarthy’s (a radio ventriloquist?) and Jack Benny’s comedies – were each heard in more than a quarter of the country’s homes, live (no podcasts, of course), every week. Think of it this way: More people listened to Bergen and his alter egos every week than watched the highest-rated television series – NBC’s Sunday Night Football – last year. Not a higher percentage; more people. Seventy-five years ago.

The first year that every Major League baseball team had its games on radio was 1939; the commercial advantages had been slow to become clear during the Depression, but it now was apparent that radio-ad sales and publicity would more than offset any resulting weakness at the gate. An increasing number of night games made many more listeners available at home during the games.

Meanwhile, the panjandrums of New York had hatched a plan to get folks’ attitudes (and perhaps their pocketbooks) out of the doldrums: The 1939 New York World’s Fair, “the World of Tomorrow,” over in Queens, was intended to perk everybody up, but by the time it opened, it seemed something of a desperate whistling in the wind. Every marketing stop was pulled out to extol its opening, including the flashy exhibit of David Sarnoff’s Radio Corporation of America, the parent of NBC. RCA had surveyed the landscape, decided that combining Hollywood and commercial radio was the wave of the future, and chose the fair’s opening day, April 30, to launch the first commercial television station and broadcast in the United States, from the top of the Empire State building to a TV receiver at the opening ceremony and, of course, everywhere else within a 50-mile radius.

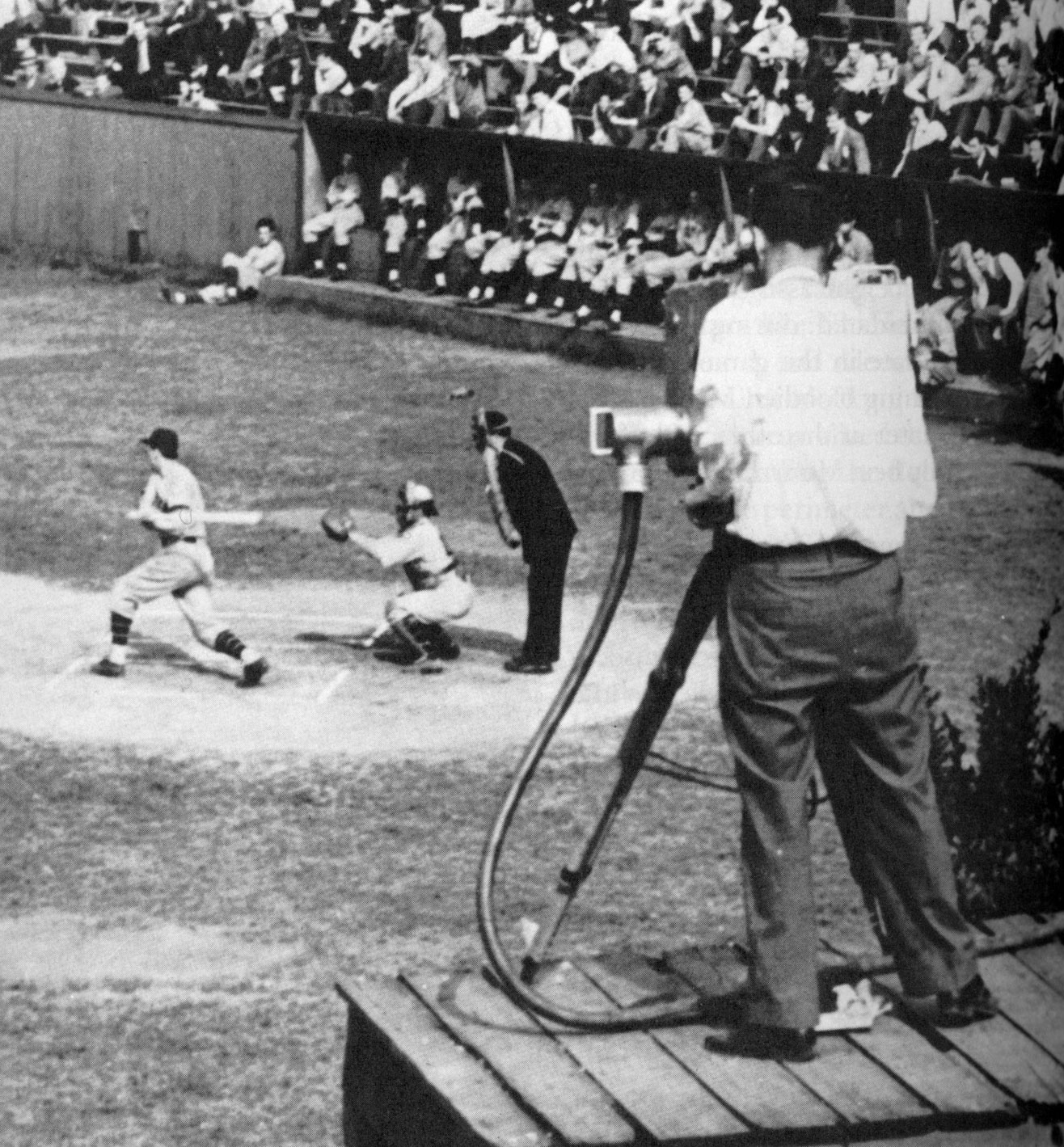

And since the good ad salespeople of NBC were not idiots, when television was born, sports television was only 17 days away. So it was that Bill Clarke’s mediocre (5-12) Princeton baseball team was the first ever to come to the plate in a televised sporting event in the United States, at Columbia’s Baker Field. The TV crew, replete with one camera, rehearsed through the first game of the doubleheader, an entertaining 8-6 slugfest won by the Tigers, and then switched on the remote transmitter to relay the signal to the Empire State before the second game on May 17 began. As NBC’s Bill Stern addressed the “crowd” out there (perhaps 40 or 50 receivers), Billy Moore approached the plate and became the first batter in TV history; he went 3-for-4 and scored the critical run in the sixth to tie the game at 1-1. Sophomore Dan Carmichael was the star, pitching a masterful 10-inning six-hitter, leaving only three men on base, and scoring the winning run in the 10th on a single by fellow-soph Stan Pearson. Could Battle of the Network Stars be far behind?

So it happened that 75 years after the first Tiger varsity ballgame, Princeton was victoriously caught up in the birth of sports television, which it would help boost into a billion-dollar business at the Providence Civic Center 50 years later. Patterns.

Speaking of which: On Jan. 1, 1938 Ken Fairman ’34 had given up his basketball and other coaching duties to become the graduate manager of athletics, a position newly moved to the University administration, as opposed to its prior incarnation running the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, a messy amalgam of alumni and faculty. So when TV came calling only a year later, the 27-year-old Fairman was in charge. He would, after being relabeled athletic director in 1941, go on to become an architect of the Ivy Agreement in 1954, overseer of the Tigers’ initial national telecasts, and the primary force behind the conception of Jadwin Gym in 1969; he retired after 34 years in charge in 1972. As college sports accelerated their cohabitation with television, three other Princeton athletes – Royce Flippen ’56, Bob Myslik ’61, and Gary Walters ’67 – have successively presided over an increasingly complex, huge, and media-integrated athletic empire, all predicated on true amateur athletes. Walters spent a term, including a year as chair, on the extremely powerful NCAA men’s basketball committee, as a result of the ’89 Georgetown game one of the most influential in amateur sports. He’s retiring July 1 as the most successful athletic director by far, according to any objective measure, in the history of the Ivy League. Additionally, he has developed (with a nod to the great sociologist Marvin Bressler ) one of the foremost ideas in academic involvement with varsity athletics: the Academic-Athletic Fellows.

Which would be a tough enough act to follow without the menace of TV (and its interactive baby bro, the Web) to the department and its charges, with its corrosive effects on scheduling, marketing, investment, you name it, always watching and needing to be fed. Ironically, television has had a far greater effect on athletics than on education; billions upon billions of dollars have been spent on televised college sports since 1939, while you can’t fill a Top Ten list with the TV series that truly have educated the general public. The all-mesmerizing eye readily lends itself to glitter, not to substance; to wisecracks, not to wisdom.

Being on the outbound communications side of a college, whether targeting alumni, high school juniors, academics, the popular press, donors, social networks, fans, or a sports conference, is by definition somewhat frustrating because it must at least partially forsake truth for spiff, and we are supposed to be in the truth business. Imagine yourself as Mollie Marcoux ’91, who will become Princeton’s athletic director in August, and imagine what you’ll have to spend your time on for the next few years, as opposed to what you’d like to do; patterns are very, very hard to change.

No responses yet