I think the teaching profession contributes more to the future of our society than any other single profession.

— John Wooden, longtime UCLA basketball coach

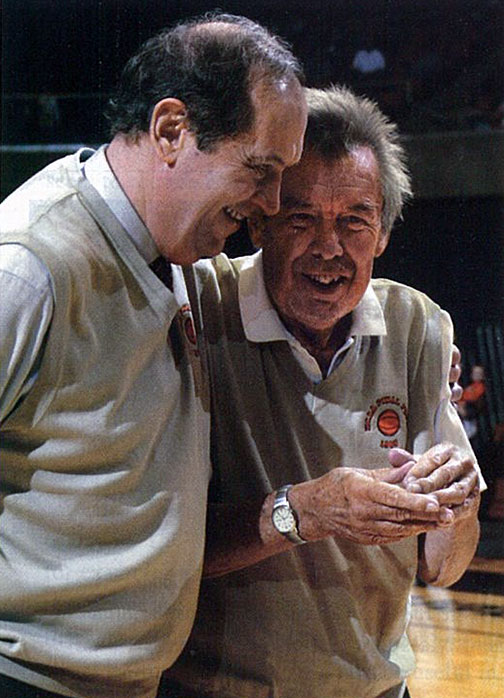

On the east wall of the Jadwin Gym lobby, at the entrance to Pete Carril Court, is a spiffy plaque honoring the momentous tenure of Butch van Breda Kolff ’45 with the men’s basketball team. Surrounding it are various headlines and game photos of an ebullient VBK, which is redundant; if anyone on this earth ever slept ebulliently, it had to be Butch.

He re-entered the Princeton scene unexpectedly, following the death of his old coach Cappy Cappon in 1961. Cappy (who first took on basketball in 1938, and now the namesake of the Franklin C. Cappon–Edward C. Green ’40 basketball coaching chair) considered it undignified – if not immoral – to recruit players, but that hadn’t stopped him from winning three of the first five Ivy championships and, unbelievably, ending up with Bill Bradley ’65 on his last freshman team. So VBK walked into a highly emotional situation, used Bradley and a free-flowing offense to recruit a pile of national-caliber athletes to Dillon Gym, and ran to the Final Four 50 years ago, including Princeton’s 109-69 victory over fourth-ranked Providence, possibly the most astonishing tournament upset in NCAA history. Brett Tomlinson of PAW has done a great job reconstructing those times in his audio history of that team, and you can actually hear Butch’s irrepressible makeup flowing through the words of his students. We’ve talked before in this space about his Tiger team two years later, captained by Ed Hummer ’67 and featuring Gary Walters ’67 and Chris Thomforde ’69 on the cover of Sports Illustrated, my pick (by a slim margin) as the best Princeton basketball team ever.

When the Ivies had decided in 1954 to bar athletic scholarships and abandon the rampant commercialization and hype that engulfed the NCAA after World War II, but also decided to remain in Division I for the sake of allowing its students to compete against the best when they could, it was seen in most critical circles as plain abdication of athletic seriousness. Bill Bradley and Butch van Breda Kolff changed that discussion in a hurry – in Bradley’s case by passing up basketball power Duke for a college that might give him a better shot at a Rhodes Scholarship; in VBK’s by flatly assuming that his aggressive defense and selfless offense could take good, smart players and turn them into great teams.

The continuing legacy has been a clear, concrete track record showing that the Ivies’ little world of genteel amateurism is not self-serving, but an actual strategy toward athletic success that contains within it psychic rewards unique in modern-day college competition. Princeton’s not in it just for the 445 Ivy League titles it’s won since 1956, but also the 46 team and 47 individual national championships over that time, plus the odd Olympic medal or professional championship ring here and there as a studly novelty. And through all of this, the athlete is completely in charge. There’s no national letter of intent to sign in high school, there’s no athletic scholarship to indenture the student’s time or priorities, there’s no way to prohibit someone from pursuing multiple sports, or for that matter from walking out of the locker room and over to John McPhee ’53’s office to focus on becoming the world’s best nature writer.

Which is exactly what a lot of those athletes might do without first-rate coaching. And obviously a coach, however talented, who regards the Ivies’ student control of athletics as simply allowing the inmates to run the asylum won’t come within a mile of Nassau Hall. So we have created a circumstance in which we are trying to hire (or develop) and retain coaches who are skilled enough to compete consistently on a national level, opposing 350 schools who can offer athletes money and less rigorous admission standards, while our coaches exercise less authority over them and, very often, are paid a good deal less than their most accomplished peers (even VBK, for all his influence, left for the Lakers after only five unforgettable seasons, for example). In the cold light of day, it’s amazing that any able Ivy coaches last long enough to develop distinguished track records; in reality there are dozens, and Princeton has had far more than its share. Although there are many personal considerations that go into such exemplars, it’s still difficult to believe our good fortune in the teacher/coaches with whom we’ve been blessed.

Speaking of Pete Carril Court. Exhibit A on anyone’s list, and discussed here often, Pete is simply the unique standard, a closet academic and compulsive teacher who almost helplessly adores his game (see: Offense, Princeton) and maniacally detests losing. The year he (as captain) and VBK overlapped at Lafayette must have melted fixtures in the gym. Twenty-nine years and 514 Division I basketball wins at an Ivy school is unlike anything you’ll likely see in your lifetime (…maybe, but we’ll get to that). But of course, in a way it doesn’t compare to Bill Tierney’s six national championships in men’s lacrosse, staying put with his nonscholarship team for 22 seasons and – my favorite stat – going 27-12 in the NCAA tourney. Stan Sieja coached the men’s fencers for 37 years and Princeton’s first NCAA trophy. Fred Samara has been the head coach of men’s track and (periodically) cross-country for an amazing 33 years and 35 Heps championships. But then, what do you say of Rob Orr, whose 85 percent dual-meet winning percentage, 59 All-Americans and 21 league championships in his 36 years – so far – as men’s swimming and diving coach are hard to wrap your mind around; nine complete generations of swimmers and their eating-club selections and thesis angst. Oy.

His counterpart on the women’s side, Susan Teeter, has been on board for only 31 years, so only has won 16 Ivy titles, including this year’s in a spine-tingling meet at Harvard. Hey, give her time. She overlapped with the godmother of Princeton women’s sports, Betty Constable, whom we talked about earlier here along with her 12 national squash championships and huge impact on the development of her entire sport from 1971 to 1991. Just retired, soccer’s Julie Shackford also coached for 20 years and had six Ivy championships and eight NCAAs to show for it, including the Ivies’ only Final Four appearance in 2004. Chris Sailer continues on in her 29th year with women’s lacrosse, with 10 Ivy championships and three NCAA titles, 350 wins and three national coach-of-the year awards in one of the most competitive women’s sports. And in fairness, we need to add the young field hockey whippersnapper (only 12 years so far) Kristin Holmes-Winn, also an NCAA champion with 14 tournament wins, a hard-to-grasp 11 out of 12 Ivy titles (including one when her four best players missed the entire season playing for the U.S. national team) and insane league record of 79-5. Of course, Peter Farrell – with 26 Heps championships – is the only head coach women’s track and cross-country have ever had, now 37 years and counting.

Confidentially, though, I truly admire coaches who can handle both male and female varsity athletes; from my hazy recollection of college I’d infer this would be schizophrenia waiting to happen. Curtis Jordan spent six years coaching the women’s open crew, including its first national championship in 1990, then moved over to the men’s heavyweights, where his 18 years included two national championships and Princeton’s first five Eastern Sprints titles. And then there are the folks who do both simultaneously: bouncy Luis Nicolao with more than 700 wins and five NCAA appearances in 17 years with the two water polo teams; Michael Sebastiani with more than 350 wins and five IFA and nine Ivy titles in 24 years with fencing; the legendary, laid-back-cool Glenn Nelson, who coached men’s and women’s volleyball to 1,086 wins – double Pete Carril’s total and all-time Princeton standard-bearer – in 31 years, and became the first coach to take two Vball teams to the NCAAs in the same year.

But what you want to know today is: What about Courtney Banghart, the fireball who in eight seasons has become the winningest women’s basketball coach in Princeton history, with five Ivy championships and this year’s astounding 31-game run? Is she the next Pete Carril, or the next Bill Carmody? It’s an especially tough call for a talented coach in basketball (never mind a national coach-of-the-year finalist like Banghart), where the big-conference TV channels bloviate incessantly, but you’d like to think that Carril, Farrell, Holmes-Winn, and a slew of others above might give Banghart pause to ruminate on the unique attractions of Tigertown as the offers from the huge-money programs roll in. I don’t envy her the decision, but I can hope.

I would love to leave you with that nerve-wracking cliffhanger, but sadly that is not to be. Missing from this column until now is the coaching equal of any of those above: Tiger alumnus, captain and national titleist, and five-time Princeton parent for good measure. Although he coached men’s squash for 32 years, 11 Ivy titles, and three national championships, Bob Callahan ’77 was only 59 when he died of brain cancer in January; it cruelly had cost him his lifetime job two years earlier. A giving and much-loved mentor and friend to everyone he met, he at least lived to see his players endow the Robert W. Callahan ’77 Head Coach of Men’s Squash position. But it still makes you feel like Ed Donovan – himself a 24-year head coach of baseball and Bill Bradley’s freshman basketball coach – felt as Cappy Cappon died in his arms on the shower floor of Dillon Gym in 1961, despondent and admiring and questioning all at once. In such awful moments, it can be useful to consider John Wooden’s reflection above and to realize that as accomplished in athletics as all these singular people are, as much as any Nobel winner or holder of endowed faculty chair or dean, they are teachers of the first rank, and among alma mater’s rarest treasures.

Dei sub numine viget.

No responses yet