Though it rains like the rain of the flood, little man,

and the clouds are foreboding and thick,

you can make the sun shine in your soul, little man:

Do something for somebody, quick!

– Teresa Piercey-Gates

Of course, it never rains on Reunions, but this year the welcoming weather on the Wednesday prior had huge tents flying in various directions in various pieces, liquid sunshine traveling horizontally across the New Jersey landscape looking for electronic devices to soak, and the long-suffering undergrad reunion crews – who 10 years from now will never believe they did this for so little money (although the T-shirts are cool) – trying not to resemble Dorothy and/or Toto on the way to Oz in the gray farmhouse.

There were those blaming this year’s 10th-reunion Class of 2005, the only class in recent decades to be wiped off Poe Field at its senior year P-rade by a violent thunderstorm, during which they bodysurfed on the field anyway along with The Band, establishing instant class espritz, if you will.

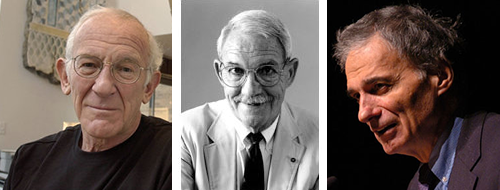

Starting off this year’s march much further up the hill was one of my favorite classes, the great 60th-reunion Class of 1955. Always having a batch of fresh thinkers around – just consider Peter Lewis and his library and arts center and Professor Bob Hollander and his Dante reunion, for examples – they outdid themselves 25 years ago by dreaming up, in response to a challenge from their (heroic/overenthused/irrepressible/didactic/earthshaking/insightful/free-swinging/legalistic: take your pick) and singular classmate Ralph Nader, what we now call an incubator in the corporate world, which they simply named Project 55. It was a service structure designed to enable other folks of good will among the Princeton alumni community to organize and jump start valuable community-service projects of vast variety, the common denominator being a large preponderance of volunteer supervision and a goal to go where no one has gone before (in the immortal words of Capt. Jean-Luc Picard).

Putting this on paper now, it seems prosaic to a degree, but 1989 is ancient history when it comes to the direct involvement of Princeton classes and other University groups in direct charity work. It was the year of President George H.W. Bush’s “Thousand Points of Light” inaugural address, which, while intending to inspire, also reflected the previous efforts of the Reagan administration to get the government out of some community-service functions and substitute leadership from other groups down the food chain. Reunions were for partying, and much less community and family-friendly: There was no Tiger Camp; there were no fireworks; 40 percent of the fifth-reunion class showed vs. about 70 percent today. There was no Princeton Prize in Race Relations, there was no Alumni Council Award for Community Service (the first one, in 1993, went to … Project 55). Wendy Kopp ’89 was still arguing about her thesis – which became Teach for America – with Professor Marvin Bressler, her unconvinced adviser. It’s hard to overstate the impact of being the first into the fray in such a potentially huge arena, and often being the first chewed up, but the members of ’55 entered with verve, and as their success and programs expanded they grew their own support structure to include younger classes, ensuring the continued vitality of what has been renamed the Princeton AlumniCorps.

If a not-for-profit can be irrepressible, this gang is it. Now comprising board members from 1955 all the way to the Class of 2012 (“Engage at Every Age” is its current motto), it keeps the ideas flowing and the projects moving. Currently involved in sweeping efforts like the Project 55 Fellowships that support new graduates (more than 1,500 to date) working for a year in community-service organizations across the country; like the Emerging Leaders professional development program for those who want to make a career in nonprofit and public sectors; like the ARC Innovators program that matches nonprofits burdened by operational challenges with experienced pro bono consulting volunteers. Crucial in all these is the coordination with the recipient organizations themselves; simply being involved in the discipline of structuring and making effective use of outside help grows the sophistication and capabilities of the partner groups (more than 500 to date). It’s a form of both viral business improvement in the nonprofit sector and broad exposure of young, talented, and well-trained people to the working machinations of community service and the public good.

Over the last 25 years, the AlumniCorps has launched a wide and intriguing range of ideas, from the National Character Education Partnership, which made seminal progress in the introduction of personal-character education into standard K-12 curricula around the United States and has spun off to become a robust nonprofit on its own; to the six-year Tuberculosis Initiative that served as a catalyst to gather together worldwide efforts to eradicate the disease as it threatened a comeback at the turn of the century; to creating the Alumni Network as a clearinghouse and learning consortium for a variety of volunteer groups at various universities from Tufts to Stanford to Carleton to Syracuse, many started in the mold of Project 55.

They’ve also inspired vastly increased efforts by all types of alumni groups at Princeton, which continue to improve in scope and impact. The Class of 1985, for example, began the Princeton University Reunions Run (PURR, of course) five years ago at its 25th to raise funds for worthy community charities; the 5K Saturday-dawn (owww, my head) race has been adopted by each succeeding 25th since. This year’s was coordinated by the Class of 1990, and the proceeds were part of the funding for a joint project by six major classes (including ’85, back for its 30th) and the APGA to buy materials for and pack 40,000 meals for impoverished children around the world, from American inner cities to earthquake-scarred Nepal, through Kids Against Hunger. Another type of effort involving multiple classes is the Princeton Interns in Community Service (PICS), a summer internship program for nonprofit partners originally spearheaded by the Class of 1969 20 years ago, which now includes multiple classes and the University’s Pace Center, and will sponsor 116 interns in 78 organizations this summer alone. This highly successful operation is now part of the Alumni Network as well. Meanwhile, widespread Princeton clubs have broadened out from the Princeton Prize, which many of them run locally, to activities to improve their own communities; the Chicago Princeton club, for instance, works with local food-distribution programs, an urban-farming business incubator, and the Audubon Society on beach conservation. And if you think all this, and the hundreds of other projects alumni groups are involved in, is simply altruistic do-goodism, you might consider that not only is Reunions attendance among the 25 youngest classes continuing to break all kinds of records, but the Annual Giving rate among the classes that have graduated since Ralph Nader challenged his classmates is 6 percent higher than the rest of the alumni body; that’s an extra 1,500-plus donors. There are indeed friendship and esprit in Princeton events beyond Prospect Avenue or body surfing on Poe Field.

In our more innocent past, I arrived at Princeton never having heard the phrase “Princeton in the Nation’s Service.” It did not take Bob Goheen ’40 *48 – about as good an example of the motto as anyone who’s ever lived – and Fred Fox ’39 long to bring us up to speed on it; the moment I heard the phrase, I realized that I was in exactly the right place. That wildly subjective attraction has not changed much from that day to this, but such attachments must be tended and nurtured, and the many fine folks of the Schools Committee, the Friends of the Library, Princeton in Asia – and on and on – and in the most profound way the Class of 1955, continue to reinvigorate thousands of alumni toward being humanitarians and servants. That way, the Class of ’55 way, is the revelation that every time you get a chance to help someone else, you’re the one who’s been blessed.

In that spirit, have a wonderful and joyous summer; check over to the right to review the “Rally ’Round the Cannon” columns from the 2014-15 academic year, and have some leisurely fun in re-perusal. Remember, there will be a pop quiz in September.

No responses yet