History is strewn thick with evidence that a truth is not hard to kill,

but a lie, well told, is immortal.

— Mark Twain

More often than advisable, I fall prey to the foibles of this virtual loony bin (the Web of course, not Your Favorite Periodical …) and go surfing across the oceans of instant history. Recently, that occurred following a magazine cover article about our old buddy here on the Interweb, Bill Gates. I idly pointlessly studiously Googled “Bill Gates Magazine Cover” and sat back to enjoy the display; there are many examples. I guess my two favorites among the plethora – and choosing was not simple, believe me – are both from Time magazine, which shows it hasn’t lost its deft graphic primacy in the print world, even today. The covers both celebrate Persons of the Year; the first with Bill and Melinda Gates flanking Bono – I infer Bono had an off year that year, maybe didn’t release an album – and the second graced with, simply, a gorgeous solo photo of Pope Francis.

When Google starts confusing Pope Francis and Bill Gates, it’s time to recall the wisdom of Mark Twain and figure out exactly what’s up here in the History Corner. Especially since The New York Times Magazine cover story that got me into this was all about Gates’ new hot cause: Big History. So we’ll need to recall the history of history and the future history of ... Anyway, today we go meta (as they say in the data-collection biz) and examine why we have a past and what to do with it, and how Princeton’s historians have and can help us point the way.

So what the blue blazes is Big History? Well, it starts with the idea that most of us are fearfully ignorant of history of any type – supposedly, less than a quarter of college seniors know that James Madison 1771 is the “Father of the Constitution,” for example. But that’s the least of its concerns; it also worries that a human being in the 21st century who doesn’t know the meaning of “extinction event” might as well be preparing for one. Focused around eight “threshold events” in our history – the first is the Big Bang, so we’re talking back aways – that lead us up to today’s discussion, it may run into trouble because it requires the adroit combination of humanities, hard sciences, and social sciences to explain how we got here, and that’s not how teachers (especially high school teachers) are taught to teach. Gates, who personally is bankrolling Big History into a high school curriculum for global distribution, will be working on this one for a while. Because, as virtually any Princetonian knows, the teacher and the teacher’s interaction with each student’s mind is the key to virtually any successful learning experience.

Of course, the best history teachers have long since understood various underlying structural influences on our human saga, be it economics – even in my era we knew about the triangular trade that enriched the masters of the New World and enslaved its workforce – or psychology, or religion, or technology (whether in the guise of weapons, navigation aids, or whatever). I’m currently taking an online (ohhh, that word again …) history course from Princeton through an 18-month-old platform called NovoEd , which allows multistudent groups to learn collaboratively. A survey course of global history from 1300 to today from Professor Jeremy Adelman (who claims to be a non-techie despite earlier Coursera experience), it is cleverly designed with in-depth exercises each week – based around his powerful lectures – and a custom-selected group of primary documents from the eras and countries in question. (My work group’s two exercises on 15th-century Chinese explorer Zheng He, for example, involved multiple levels of Asian cultures of which I’d never heard. And my favorite nugget from the course is Adelman’s connection of the Chinese tea trade to the Enlightenment.) But despite the novelty of my erudite collaborative work group spread across 10 time zones, it simply does not have the gravitas of being in a good precept (thank you again, Woodrow Wilson 1879).

Which may be exactly why the teaching of history at Princeton got serious precisely when precepts did, during Wilson’s whirlwind eight-year presidency; he was a serious historian who hired T.J. Wertenbaker , who along with Dana C. Munro became renowned scholars, department chairs, and presidents of the American Historical Association. Even so, history was lumped in with politics until 1924, when a combination of rising interest after World War I and the new four-course plan and its attendant senior independent work demanded a larger and more specialized teaching faculty. Fortunately, strong teachers like Beppo Hall and Buzzer Hall (not related, and very different in style), Munro and Wertenbaker were ready to go, and the department has, ever since, had a notable emphasis on the classroom, even in a university where teaching is taken seriously. It seems that every era has its memorable teachers of history. The mid-century had Jim Billington ’50 (now the librarian of Congress), Eric Goldman, Cyril Black and Joseph Strayer; the latter decades Ted Rabb *61, Arno Mayer, Natalie Zemon Davis, Charles Gillispie (who in many ways invented the history of science), and one of my favorites, Jim McPherson, the magnificent writer on the Civil War whose honorary doctorate from Princeton this year rivals his position as an honorary member of our Class of 1970. Folks like Adelman, Sean Wilentz, Nancy Weiss Malkiel, and Tony Grafton continue to person the barricades today. It is a rare undergrad indeed who leaves Princeton without a strong history teacher in her bundle of memories.

But since we’re focused on the classroom, we should note particularly two of the greatest among these greats, and realize again how much of history is tied up in the historian himself.

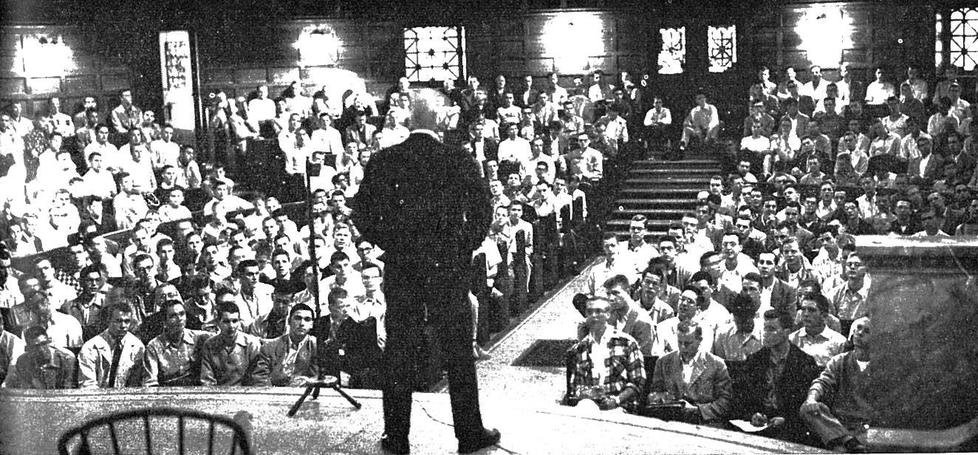

The aforementioned Walter “Buzzer” Hall (whose nickname stemmed from an obtrusive hearing aid) taught modern European history, making Garibaldi, among a host of others, a living character for undergrads from 1913 to 1952. A member of Yale’s class of 1906, he taught precepts with his bulldog, “Eli.” He lectured in his underwear. He stood on top of desks. His lectures usually started at – believe this or not, it’s true, children – 7:40 a.m. His number of verses in “The Faculty Song” seems infinite, but perhaps the best notes “On Garibaldi’s life and death, he yells himself quite out of breath.” His final lecture had to be moved into Alexander Hall in a feeble attempt to handle the crowd, but at least a six-piece pep band managed to squeeze in so the whole auditorium could sing “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” He was almost always voted the best teacher in the college, and the Class of 1952’s dedication of its Nassau Herald to him cites his personal import: “As scholar and friend, this Professor of ‘Things in General’ has stimulated generations of Princetonians to think for themselves.”

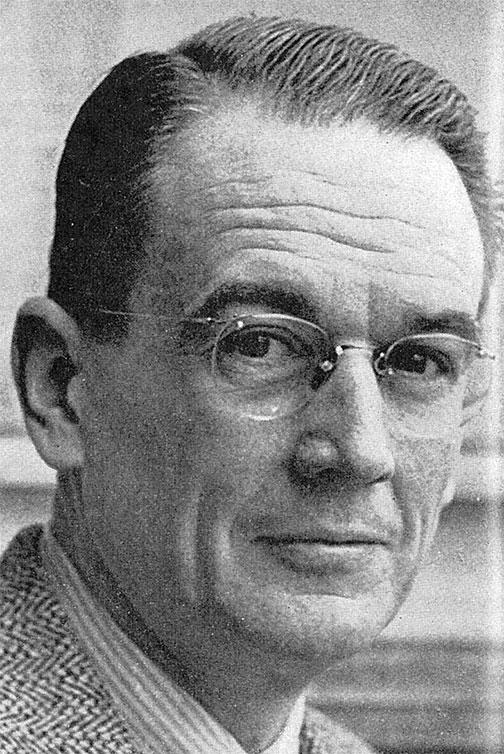

Four years thereafter, the Class of 1956 dedicated its Herald to Jinks Harbison ’28, wildly dedicated Princetonian, valedictorian of his class, president of Triangle, devout Christian, and master historian of the Renaissance and Reformation. His entrancing lectures treated the period and Erasmus (his own monumental equivalent of Hall’s Garibaldi) as challenges to be eternally questioned, their meaning examined Socratically and constantly enriched; his “Faculty Song” verse warns “he seldom marks above a three [B-].” His faculty memorial noted that “his great gift as a teacher was to make his students raise important questions in their turn.” His death of cancer at age 58 in 1964 was a tragedy that robbed him of his own “last lecture,” but PAW stepped in and carried his entire six-page tour de force closing course lecture, framed as a trial with the Church facing off against Philippe the Fair, William of Occam, Alexander Borgia, Niccolo Machiavelli, John Calvin, and Copernicus; philosophy mixes incessantly with psychology, science, politics, and inertia. Every sentence is a marvel; you can see it here.

The Danforth Foundation named its teaching award for Jinks Harbison, and Princeton president Bob Goheen ’40 *48 used the occasion to give a passionate talk “In Defense of Teaching” – the tendency of research to dominate prestige universities was a fear even in 1966 – wherein he noted: “Rote learning never was much good … the citizen of tomorrow must master the ways of analysis, must search deeply, if he is to cope with the uncertainties and changes of the decades ahead.” Not a bad prophecy 30 years before the Internet.

This is the huge challenge to the MOOCs and the Big Histories of the present age: not their underlying content or conception, but the ability to bring each student to the point of searching deeply, of discovering deep truths (if only about herself) from the muddled data points of history. As David Christian, the founder of Big History, sees it, the largest threshold event to date – in the entire history of our universe – is the point at which humans developed language to convey accumulated learning to those they would never see; the point when history popped into being. Note: There were likely only two people involved.

No responses yet