I think some day you may have flown too high,

so that immortals saw you and were glad,

watching the beauty of your spirits flame,

until they loved and called you, and you came.

—Epitaph of H.A.H. Baker 1914

Your attention is directed to Saturday, Nov. 16, 2013, when we’ll see on campus a confluence of events that set the nostalgic mind soaring in imagination. Ninety-nine years and 364 days following his valedictory appearance on a football field, we will see the Hobey Double, as I’ll dub it: Following the 1 p.m. football game against Yale in Princeton Stadium, the men’s ice hockey team will skate at 7 p.m. in Baker Rink against Harvard. Were he available, this conveniently would give Hobey time between starring in both matches to run the postgame press conference, sign autographs for small children, have a steak at Ivy with an E-commerce billionaire to secure a new endowment for impoverished applicants, and tune up the Zamboni to minimize the athletic department’s carbon footprint. The unnerving part of this scenario (apart from the idiocy of the NCAA allowing varsity hockey games as early as Nov. 1) is that it’s clear that those who saw him perform live a century ago would readily believe this idea was perfectly plausible – and in fact, would expect it of Hobey. F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 would even be there to write about it.

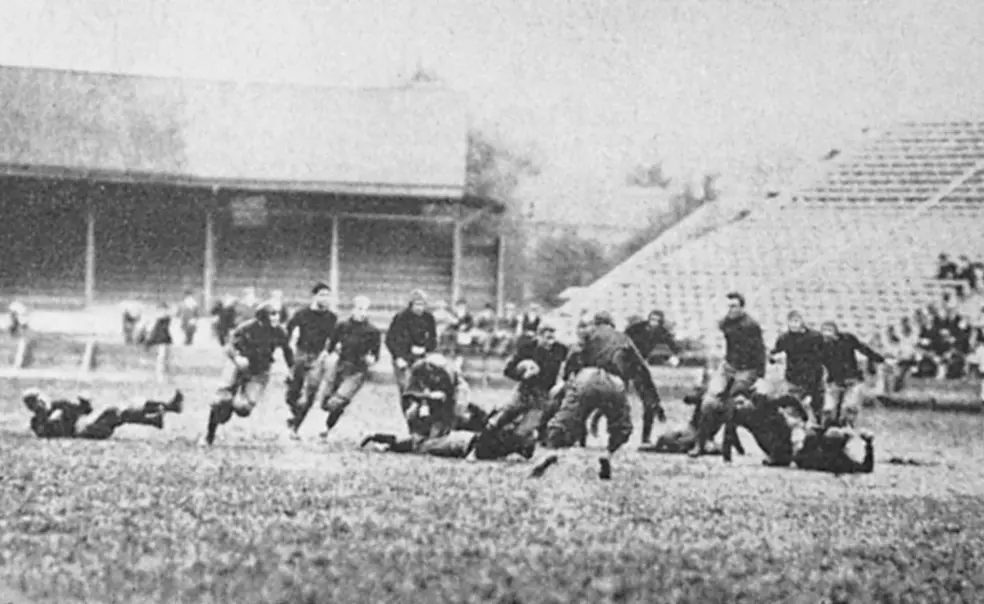

When we left the gridders last year, we noted that their bonfire celebrated many prior joint Harvard/Yale triumphs, including the very first in 1878. Three years after that, a young Princeton legacy named Bobby Baker 1885 came to campus; he was the stud halfback and scored touchdowns and goals by the passel for three years, and the team went 23-3-1 … but never beat Yale. He then joined the family business in Philadelphia, and in turn had two sons of his own, the younger of whom was the Golden Boy, Hobart Amory Hare Baker 1914 – the only person in both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Hockey Hall of Fame, namesake of Amory Blaine of This Side of Paradise and the first college campus hockey arena in the country and college men’s hockey’s most valuable player award, as well as captain of the 141st Aero Squadron of the American Expeditionary Force. He won the Big Three and national championship in his first football season, effortlessly running and kicking his way around the field, his shock of golden hair unencumbered by helmet or, seemingly, undue concern about interference from the mortals who happened to share the field with him. He never lost to Yale.

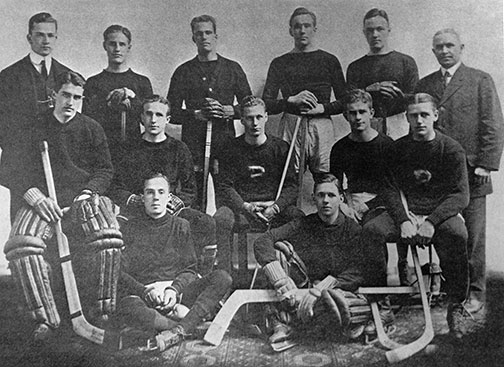

That was his backup sport. First introduced to ice hockey at St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire at age 11, before Hobey graduated seven years later his preppies had beaten the varsities of both Princeton and Harvard. He was simply a wonder on skates, with no individual and very few teams able to seriously slow his lethal rushes down the ice. Princeton won national championships (playing most of its home events in New York City) in his sophomore and senior seasons, and went 27-5 against American teams during his career; the year prior to his joining the varsity, the team had been 6-4, and the year after he left it was 6-6. After graduation, he played amateur hockey (accepting money for sport horrified him; he earned his pay working during the day at J.P. Morgan) with the St. Nick’s club in New York, and frequently faced off against the best players in the world, mostly professionals from Canada, who as a matter of honor (oh, that word again) did their best to send him to the morgue. It didn’t work; he got roughed up once in a great while, but scored anyway. The Hockey Hall of Fame opened in 1945; from across the 60 or so years ice hockey had been organized to that point, only 11 players were chosen as inaugural inductees, the consensus bedrock of the sport: Ten Canadians and Hobey Baker.

After St. Paul’s and Princeton, the desk life at J.P. Morgan drove Baker crazy; with only evening hockey for relief, he needed new recreational excitement to soothe his competitive demons. He tried cricket (a strong baseball player, he was allowed only two sports in college), he tried polo, he tried auto racing, then he found a challenge to sink his teeth into: flying. He joined up with the civilian air corps, and legendarily buzzed the Yale game crowd at Palmer Stadium Nov. 18, 1916, before landing to attend the game. The Tigers then lost their third straight to the Elis following his graduation.

Baker headed for Europe as quickly as he could when America and Woodrow Wilson 1879 (he always pops up somewhere…) went to war; they made him learn French, they made him wait for maintenance parts, but he finally got to fly and (more important) lead; he compared the feeling of aerial combat to that of a big sports event. By the Armistice he was a 26-year-old captain with at least three kills and an entire squadron under his command, its planes painted orange and black. He died in one of them in an infamous voluntary test flight hours before his scheduled trip home to the States on Dec. 21, 1918. There were those who suspected he easily could have landed the stricken aircraft safely, but chose to die instead. His packed memorial service at Trinity Church in Princeton was covered by The New York Times. Baker Rink, the first college ice surface in the world, was built in his memory by public subscription (90 Yale men and 172 from Harvard contributed); at its dedication in 1923, Hobey would have been 30 years old.

I briefly recall these events here because there are many, especially among the younger folks, who a century later don’t know them well, but for the ardent historian there are fine literary works in which to find Hobey and his fleeting era as America’s great amateur sports hero, notably The Legend of Hobey Baker by the late PAW Editor John Davies ’41 and Emil Salvini’s Hobey Baker, American Legend (do you think Hobey was legendary?), and the haunting novel by Mark Goodman Hurrah for the Next Man Who Dies. But for my money, and short attention span, the best evocation is the legendary Sports Illustrated feature from 1991 by the late Ron Fimrite, one of the storied stable of writers of SI’s golden age, that restored Hobey to the sporting public’s consciousness. Remarkably, Fimrite’s not one of the phalanx of wonderful Princetonians who’ve written for the magazine – Frank Deford ’61, Peter Carry ’64, E.M. Swift ’73, Merrell Noden ’78, Alexander Wolff ’79, and Grant Wahl ’96 pop to mind – but he captures the ethos of the era perfectly, and powerfully argues that Hobey was almost devoid of purpose once the war was over. Most important to us here, Fimrite explicitly outlines what he terms The Hobey Code: “A star player must be modest in victory, generous in defeat. He credits his triumphs to teamwork, accepts only faint praise for himself. He is clean-cut in dress and manner. He plays by the rules. He never boasts, for boasting is the worst form of muckery. And above all, he is cool and implacable, incapable of conspicuous public demonstration.” Fimrite notes that this ideal dominated college athletics, and extended beyond, for decades; this was the code of Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, Joe Louis, and Roger Staubach. Of course, decades after Ivy alumni started to head to the pros – soon after Hobey, not only Columbia’s Gehrig but Moe Berg ’23 and Charlie Caldwell ’25 played in the majors – the Code reappeared in the career decisions of Dick Kazmaier ’52, who spurned the NFL, and Bill Bradley ’65, who went from Princeton to Oxford for two years while the NBA stewed. Princeton president John Grier Hibben 1882 *1893, in his eulogy at Hobey’s memorial service, made the connection between the Code and Princeton explicit: “The spirit of this place was incarnate in him, the spirit of manly vigor, of honor, of duty, of fair play, and the clean game.” Seeing the “42” flags around campus this fall should recall Hobey (no uniform numbers in his time) as much as Kazmaier and Bradley.

This is, however, the 21st century, and I think we don’t really expect to see the Hobey Code much in evidence today. Even the Tim Tebows of the world manage to turn their humility into a marketing machine; steroids abound. There are the Roberto Clemente, Lou Gehrig, Walter Payton and Lady Byng awards, of course, but they go to people who, after all, earn millions of dollars per year. Perhaps the foremost recent example of the Code is that of Pat Tillman, the Arizona Cardinals’ safety who spurned a few million NFL dollars to enlist in the Army after 9/11, and subsequently was killed in uniform 85 years after Hobey. Who knows: Transplanted to the large standing military of today, Baker might have traded his Spad for a Black Hawk chopper with orange-and-black Tiger decal and flown relief missions for Afghan civilians in enemy territory. I doubt, now as then, he’d be happy working for J.P. Morgan.

1 Response

Tim Rappleye

8 Years AgoGregg, have been a...

Gregg, have been a "Hobeyologist" since the Fimrite article, but finally saw your piece. Well played, especially the last 'graph. Thanks for the contribution; the Pat Tillman reference was first-rate.