Rally ’Round the Cannon: Bohm’s Away

The university in America is the archive of the Western mind,

it’s the keeper of the Western culture, and the foundation of the Western culture

is consent, it’s freedom. Princeton, or any other university great or small,

has the obligation of transmitting from one generation to the next that heritage.

The faculty and the administrators of a university can do that only if they are free.

— Adlai E. Stevenson II 1922, addressing the Class of 1954

I would shudder for this country if I thought that we too must surrender to the sinister figure of the Inquisition, of the great accuser. I hope that the time will never come in America when charges are taken as the equivalent of facts, when suspicions are confused with certainties, and when the voice of the accuser stills every other voice in the land.

— Adlai E. Stevenson II 1922, University of Wisconsin, 1952

You might suspect that Adlai Stevenson 1922, once editor of The Daily Princetonian, would not have been a fan of Instagram, DOGE, nor the hilariously mislabeled current U.S. Department of Education. Hold that thought.

It’s always a goal here in the History Corner to investigate stuff about Princeton you didn’t already know. Today’s adventure — in contrast — features a whole pile of folks you are familiar with, including some they’ve made movies about or written books on or named global prizes for or whatever. This is incidental, a result of Princeton having been a global center of theoretical physics during the most recent period of the American government trying to intrude and tell the professoriate how they should behave, and even how they clairvoyantly should have behaved decades before.

You’re even familiar with the modes of oppression involved in the various confrontations we’ll revisit, via recent dramatic experience. If you saw Oppenheimer last year, or Good Night and Good Luck at the movies (the role of a lifetime for David Strathairn) or currently on Broadway, you know the drill of government “hearings” dripping with innuendo from those who are handed power by the public and use it primarily to glory in the exercise of power.

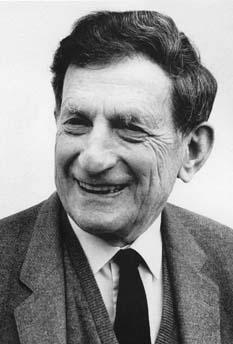

So, faced with a challenge to find a nice fresh starting point for you to begin our tale, I give you Professor David Bohm. To be honest, if you are a quantum physicist, you likely do know him, but may be unaware he has anything to do with Princeton. Generally remembered as British, he is on that peculiar shortlist of facile folks who might have won a Nobel Prize but didn’t, like Princeton’s John Wheeler or Bob Dicke ’39. This was due to Bohm’s singular expertise, which played at the boundary of quantum mechanics and neuropsychology, leaving very few others to knowledgably critique such advances as the Bohm-diffusion, De Broglie-Bohm Theory, or the Aharanov-Bohm Effect, evaluate the Bohm Criterion, or carry on a Bohm Dialogue. It didn’t help that most of this took place at the University of London, where he spent his final 26 years as a professor, rather than the glow of Oxbridge. This was not happenstance; for a long while he was a citizen only of Brazil.

But he was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in 1917, and if this leaves you bemused and/or befuddled, we’re ready to go. A very bright young lad, the son of Jewish immigrants, he headed for Penn State, got his bachelor’s degree in 1939, and followed his professor to the West Coast. He was part of the nuclear research group built by J. Robert Oppenheimer at Berkeley (that you saw in the movie); which incidentally contained various radical unionists and protocommunists; Bohm even had a thing with Betty Friedan. (History! You can’t make this stuff up.) In 1942, Oppy wanted to bring him to Los Alamos, New Mexico, to work on the Manhattan Project, but the Army said no way because of his pinko friends. So Bohm kept the lights on at Berkeley and did a series of calculations for his thesis that were so useful at Los Alamos they were immediately classified, so he then couldn’t even access them to write his own thesis. Oppy certified his work in absentia, and Bohm was granted his Ph.D. in 1943.

By 1947, with postwar nuclear tests concluded and George Kennan 1925’s Long Telegram already setting the stage for East-West tensions, the nuclear scientists of the Manhattan Project returned to the mainstream. Oppenheimer, Bohm’s thesis adviser, became director of the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, where he caught up with his friend Albert Einstein. Richard Feynman *42 was off to Cornell, John von Neumann back to IAS with Einstein and Kurt Gödel. In the University chemistry department, Nathaniel Furman 1913 *1917 and Hugh Stott Taylor returned; in physics, Wheeler, Feynman’s instructor, was back along with Eugene Wigner, who had participated in the Einstein letter to Franklin Roosevelt that generated the Manhattan Project, and the department head, Henry DeWolf Smyth 1918 *1921, now almost as famous as Einstein and Oppy as the author of bestseller Atomic Energy for Military Purposes, the astonishingly frank 1945 public history of the Manhattan Project and the creation of the atomic bomb. This was, for all purposes, as powerful a scientific community as existed anywhere on the planet.

This seemed to impress the House Unamerican Activities Committee not one little bit. As the U.S. now faced confrontation around the world with the Soviet Union and the Cold War took shape, the committee’s fixation with domestic commies under every bed gathered steam, decimating Hollywood (rather odd, since the biggest secret in Lalaland was whether Bogie wore a toupee) and heading straight for various academic supposed fellow-travelers.

Oppenheimer took over at IAS in early 1947, recommended that the University hire Bohm, and at only 30 Bohm became an assistant professor. When not in the classroom, Bohm began working for Einstein, who was always in need of help with math, not his best thing. Meanwhile, the committee had found a nice juicy fishing hole for likely “comsymps”: the radical Berkeley scientific community of the late 1930s, including Oppenheimer’s group. While looking for a traitorous “Scientist X,” the committee called Bohm to testify in 1949. He refused to answer questions or name names, standing on the Fifth Amendment. The University put out a really careful statement, saying his work was “zealous and effective.”

At Princeton, the statement continued: “He has given instruction chiefly at the senior and graduate levels and done research in the field of quantum mechanics. None of this work was secret in character. In fact, the Physics Department has not been engaged in secret work since 1946. He has been regarded by his Princeton colleagues as a thorough American and at no time has there been any reason for questioning his loyalty toward the government and democratic institutions of the United Sates. Dr. Bohm’s appearance before the House Committee seems to have grown out of circumstances that developed while he was at the University of California. Princeton has no information in this matter other than what has appeared in the public press. His appointment at Princeton was based upon strong recommendations as to his scholarly and personal qualities, and his outstanding record in preparation for the teaching profession. It is the earnest hope and belief of Dr. Bohm’s associates that he will demonstrate that his activities prior to coming to Princeton have in no sense impaired his present and future usefulness as a member of the scientific faculty of a university dedicated unreservedly to the welfare of this country.” It pointed out, ominously, that he was only under contract until 1951.

Unsurprisingly, Bohm was indicted for contempt of Congress in December 1950, after the committee gave up trying to find anybody from the Berkeley days who had seen him do, well, anything. He was suspended with pay, supposedly according to University policy. He was found not guilty and reinstated to his post, but the Committee of Three did not renew his contract and in 1951 he was indeed gone, with grim prospects elsewhere.

With his teaching and research abilities vouched for by Oppenheimer, Einstein, Smyth, Wheeler, von Neumann, and the others, Bohm, just having in 1951 published a well-received book on quantum theory and having already discovered Bohm diffusion, ended up in … São Paulo. That’s in Brazil. The U.S. confiscated his passport (why?). It took him 10 years and stops in Israel and Bristol to earn his offer of a professorship in London, where he became a fellow of the Royal Society for good measure. He got his American citizenship back in 1986, six years before his death.

So, the burning question is this: With all these honored and powerful people to attest to his skills, and his stunning expertise in his chosen field, why would President Harold Dodds *1914 and the trustees choose to let Bohm go? To Brazil? Princeton and the IAS didn’t burn him at the stake, but they hardly covered themselves in glory in the eternal fight for truth.

And just as if to ensure we remember, recall that Oppenheimer himself then got dragged to Washington in 1954 and stripped of his clearance on similar puny charges, as vividly portrayed in the movie. The one member of the Atomic Energy Commission to vote in his favor was an outraged Henry DeWolf Smyth, who then resigned in disgust.

I saw the other day that President Chris Eisgruber ’83 feels today is the worst government attack on higher education since the Red Scare. This is what he’s talking about, folks. And what Adlai Stevenson 1922 and Edward R. Murrow were talking about in the shadow of Joseph McCarthy. And they all reach the same conclusion –— we have to do something about it. Not the think tank next door, not the courts, not the faculty senate, not the big law firms. Us. Ideas welcome.

1 Response

Jim Newcomer ’57

9 Months AgoRight Choice Does Not Require a Majority

I’m with our university in resisting tyranny, and I urge the whole institution to continue standing up for all our people — and our democratic institutions as well — in the face of this threat. So far it looks as if we’re doing better this time around than Whitey Dodds did in the McCarthy era. It may get more difficult with time to withstand the assaults to all kinds of freedom, both academic and personal. If we stand together and take our stance early and hold it, we will win in the long run.

I hope that I am joined by the overwhelming majority of my fellow alumni in this view, but the right choice does not depend on having a majority. In this case it’s just right.