Rally ’Round the Cannon: Cinderella Wins, 49-50

In this corrupt age, the NCAA needs the Ivy League more than the Ivy League needs it.

– George Vecsey, The New York Times, March 26, 1989

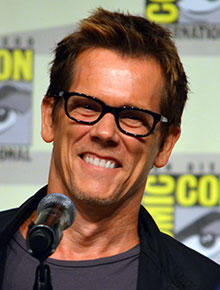

If John Donne felt “no man is an island” 400 years ago, imagine what he’d think of Twitter. Our interconnectedness now is memorialized in such cultural niceties as your Erdős number and Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon. Even an ivory tower like Princeton doesn’t operate in a vacuum or disregard the outside world, and I don’t mean just in obvious ways like obeying the laws of gravity or the laws of OSHA. The Six Degrees of Higher Education involve everything from hiring away Nobel prizewinners to setting nominal tuition prices to U.S. News & World Report rankings (although we don’t pay any attention to those, heh, heh).

Which, God help us, brings us to the NCAA and its peculiar relationship with academia and/or reality. Since this is after all the History Corner, we need to remember that Princeton and the other Ivies really don’t have much cause to complain; we created this athletics mess in the late 19th century as an odd combination of manifest destiny, the first industrial age, and the ancient Roman circus maximus. Strange people were recruited off the streets to play for varsities; various Poe brothers would flunk out of school every spring, then be readmitted in the fall in time for football season.

The Ivies were also crucial in reigniting the Olympics in 1896 (speaking of ancient circuses), sort of a global NCAA with extra rhinestones and its own hymn. Fortunately, the Adults in the Room were decisive and firm: President Teddy Roosevelt (a Harvard boxer) laid down the law to the football powers in 1905, essentially saying: “Stop killing people.” With such an exalted bar to aim for, the colleges gleefully constructed impenetrable sets of rules, conferences, and alumni clubs to ensure that the most critical document for any institution of higher learning was its contract with Nike. If you feel I’m overstating, you might wish to consider the recent article by Nathaniel Popper of The New York Times detailing NCAA recruiting of women soccer players … in eighth grade.

The Ivies, suffering perhaps from founders’ remorse, did establish their own more stringent codes in the 1950s (we earlier discussed that in the context of Dick Kazmaier’s Heisman trophy season), but chose to remain in Division I despite their abolishment of athletic scholarships for a simple reason: They wanted their students (hey, remember the students?) to be able to compete with the best, when they were good enough. Like most human endeavors, this worked, partially. In the 25 years after the formal Ivy agreement in 1954, the league indeed had increasing trouble competing nationally in football, but some other sports fared better: Cornell won national championships in hockey and lacrosse, Princeton and then Penn made the Final Four in men’s basketball, Princeton won the NIT when it was still nationally competitive. New women’s varsities were often very successful in the old AIAW (Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women). The old strengths in squash and fencing continued. But the Ivy presidents felt there were still liberties taken in the admission of athletes, so in 1985 they imposed the Academic Index (AI) on league coaches and admission offices; to oversimplify, recruited athletes had to statistically resemble the academic profile of the student body as a group, and could not individually be admitted if their projected grades were too low.

This coincided (?) with a downturn in men’s basketball talent around the league, and the result was not only the first champions in 25 years not from Penn or Princeton (Brown ’86, Cornell ’88), but rampant mediocrity – the nadir was the ’87 Penn team, which won the league while going 13-13 overall before being humiliated by North Carolina 113-82 in the NCAA tournament. The following year, Cornell eked out the title after Pete Carril’s team (captained by John Thompson III ’88) lost three excruciating one-point league games in a row; the Tigers brutalized the Big Red by 21 in their last game, but then had to stand by and watch as the Ithacans (RPI rating: 128) got whacked by Arizona 90-50 in the NCAAs. The Ivies had become a joke.

From this morass sprang one of the transcendent turning points in American amateur sports.

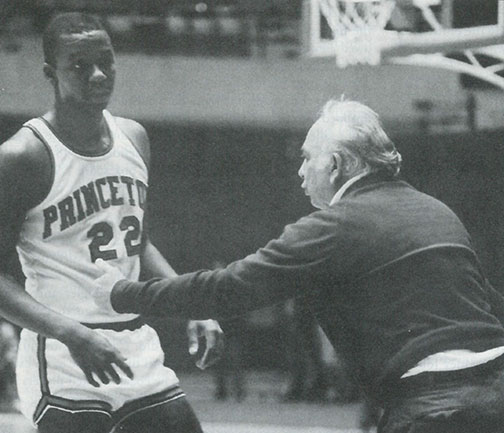

Carril, with a new 1988-89 team dominated by sophomores (including Kit Mueller ’91) and freshmen (including George Leftwich ’92), led the Tigers through a season of self-discovery, beating every Ivy team at least once and winning the league while going 19-7 for their best year since Craig Robinson ’83 and Gary Knapp ’83’s squad six years before. (They would go on to win three more titles in a row, Carril’s only four-peat.) Given the Ivies’ recent tournament track record and a nonentity RPI rating of 137 (thanks to the awful league competition), Princeton got slotted at number 16 against No. 1-seed Georgetown, coached by Thompson III’s father John Thompson Jr., five years off an NCAA championship, winners of the Big East regular season and tournament, featuring All-American guard Charles Smith and the fearsome freshman center Alonzo Mourning.

Now, 25 years ago the NCAA tournament was just rounding into mega-event shape. ESPN, only 10 years old, had bought a big package of unwanted early games from the NCAA and painstakingly built it into a sports geek’s dream; gradually everyone realized how much money was out there for the picking (Nike was an early sponsor). And consequently, the big conferences (Big Ten, ACC, Big East, Pac-10, you know the drill) were on the warpath to grab even more playoff slots – i.e. money – than they had. At the NCAA convention in January 1989, a proposal to cut back the number of automatically qualifying (AQ) conference champions almost passed, and likely would have cost the Ivies their lone slot. High-profile commentators like ESPN’s Dick Vitale wanted the AQs done away with completely.

Which brings us and the NCAA to March 17, 1989, which in the Newtonian sense of time is indeed 25 years ago, but in Einstein’s relative universe over in old Fine Hall is but moments away from us in TV time, although it involves the super slo-mo Princeton offense rather than the speed of light.

The stories surrounding the Tigers’ mesmerizing game are legend; getting out to an 8-2 lead, causing Georgetown coach Thompson to change to a zone defense to avoid a first-half rout, leading by eight (29-21) after a first half of 50 total points, unbelievably low for an NCAA tournament game with a shot clock. And indeed, the second half was different: The two teams combined scored 49.

The Tigers (led by point guard Leftwich and “center” Mueller) played keepaway so well that the they got only five foul shots in the entire game; even their layups (they had 15) were clean. They outscored the Hoyas 47-39 from the floor. They held All-American guard Smith to four points; Mourning was the only Hoya to score more than eight. Princeton had only seven turnovers against a fearsome Hoya press; Mueller, the “center,” had more assists (eight) than Georgetown (seven). Princeton led by 10 just after the half; the Hoyas’ first lead was 29:38 into the game, and their largest was two points. Mourning probably should have been ejected for throwing an elbow to Mueller’s face with four minutes to play; his two blocks in the last seconds – one clean, one sortamaybe, none called – are discussed to this day among coaches, sportswriters, and nutty fans of the various John Thompsons at both schools. Carril’s definitive statement on the lack of a foul call: “We’ll take it up with God, when we get there.” It built steadily to become the highest-rated basketball game in ESPN’s history to that moment. The nominal score: Georgetown 50, Princeton 49.

But what you need to understand is the emotion; the screaming of the 12,000 instant Princeton fans in Providence reverberated all the way to the boardroom at CBS. Take a look at the game tape and feel the madness as it builds:

Dick Vitale, who had offered to be the Tigers’ ballboy for the second round if they won, ended up his ESPN broadcast in a Princeton sweatshirt; the concession stands sold out of Tiger memorabilia; Alex Wolff ’79 got a two-page spread in Sports Illustrated to tell the agonizing story of alumnus Thompson III, in the stands, trying to choose between his No. 1 father and his No. 16 teammates. As Georgetown continued on to win its next two games, the instant legend grew. New York Times columnist George Vecsey and, yes, even the Hoya coach took up the small conference AQ banner; Thompson, whistling past the grave, said the Ivies should get two slots.

And (surprise!) eight months following Princeton’s triumphant “loss,” the NCAA and CBS came to a monumental agreement, the first $1 billion “amateur” sports-rights contract ever (spread over seven years), for every single NCAA tournament game. “We felt the first round had become a very exciting part of the coverage and wanted it to complete the picture,'” drooled Neil Pilson, president of CBS Sports. Translation: We love the Cinderellas, don’t screw this up. Removing existing AQ bids from the tournament never came to an NCAA vote again.

Since March 17, 1989, George Mason, Memphis State, Butler, and Virginia Commonwealth all have been to the Final Four, to the adoration of millions. Amazingly, even Carril benefited as his 13th-seeded Tigers – who might never have had a bid without the Ivy AQ – beat defending champion UCLA 43-41 for his legendary last win in 1996. The NCAA and CBS cheered him all the way to the bank. But to this day, no No. 16-seed has ever beaten a No. 1.

Meanwhile, today’s Georgetown coach, John Thompson III ’88, would gladly play anyone, anywhere rather than the Princeton Tigers; call it Six Degrees of Pete Carril.

No responses yet