“It feels like times have changed.”

— Pat Garrett, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, 1973

The Lincoln County War proper began in the New Mexico Territory on Feb. 18, 1878, a couple of years after the Little Big Horn, when Sheriff William Brady, who was in the pocket of local monopolists in the dry goods and cattle trade, sent his deputies, more generally known as the Jesse Evans Gang, to collect some horses from a rancher who opposed The House, as the monopoly was known. In the end, they caught up to the rancher, John Tunstall, and three of them killed him in cold blood. His cowhands and other allies formed a counter-vigilante vigilante squad, called the Regulators, which went after the Evans Gang, and the war in this territorial outpost was on. Among a couple dozen other casualties, the Regulators caught Sheriff Brady alone and killed him on April 1.

You may be aware of this already, but perhaps you can’t quite place the details. One of the Regulators who caught Brady was William Bonney, the legendary Billy the Kid, and one of Brady’s successors in the sheriff’s job was an itinerant cowboy by the name of Pat Garrett, who chased Billy down and killed him at Fort Sumner in 1881. Various versions of the story have been more or less accurately told ever since, including expensive Hollywood ones such as Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, The Young Guns, and John Wayne’s Chisum — named for John Chisum, one of the ranchers who backed the Regulators.

At this juncture you, the Informed Historian, will be forgiven for searching the masthead above to check if you’ve ended up on the wrong site by mistake. Don’t Panic (as Douglas Adams or Elon Musk would say).

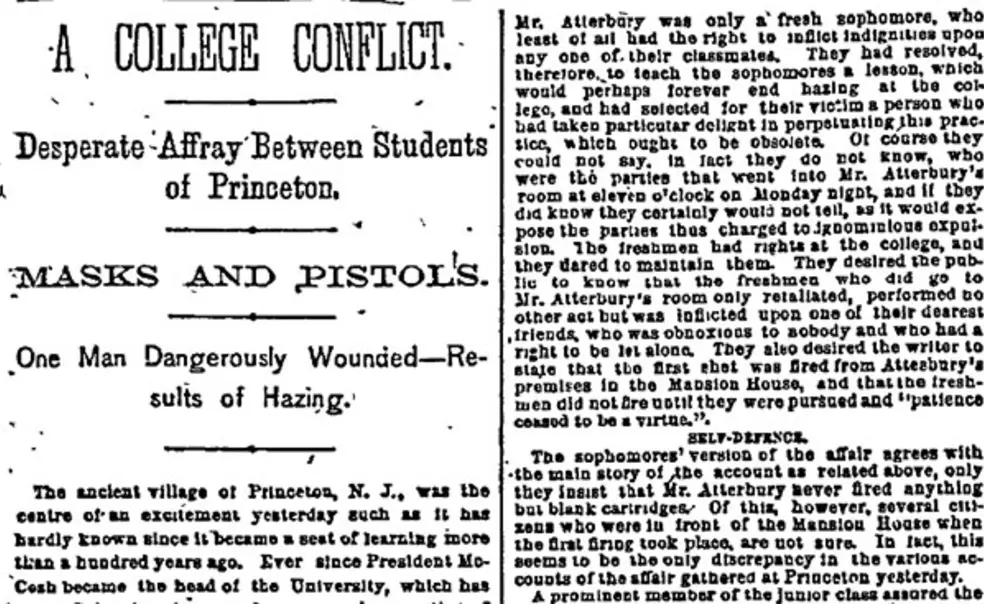

Earlier in 1878, a pair of Princeton sophomores by the names of Albert Atterbury 1880 and Berdine Carter 1880 had inveigled a naïve freshman, Louis Lang 1881, to their rooms in the Mansion House off campus and, for whatever imagined sleight, their classmates had given him a serious hazing, although the details are murky. Now, you’ll recall from earlier columns that these were the days of fierce (remember the flour picture?) inter-class rivalries, well beyond Cane Spree, and apparently the freshmen of ’81 were a prime example. They plotted revenge, and on Monday, Feb. 18 — the day John Tunstall was murdered far away in Lincoln County — a dozen or so went to the house and overwhelmed Atterbury and Carter, administering a whuppin’ and head-shaving, then quickly cleared out. The sophomores grabbed their handguns — we’re going to pause here for effect and let that one sink in for a second — and fired blanks (supposedly) out the windows at the fleeing frosh, raising a significant din. Members of the two classes spilled outdoors, and when the sophs caught up with them, the freshmen fired back — i.e. they had come to the revenge hazing armed — and Atterbury was wounded in the thigh (obviously not by a blank), but only sustained a “slight flesh wound” according to the not-particularly-sympathetic Princetonian.

It took a couple of days for the faculty to get organized, but on Feb. 20 they suspended 10 of the freshmen involved in the revenge attack, and those 10 plus sympathetic classmates immediately caught the 5 p.m. Dinky to the Junction, where they waited for the 5:45 New York train to take them home to mom for further questioning. A mob of sophomores got wind of this, followed on the next Dinky, and the two classes faced off at the Junction with pistols and heavy clubs, but were thwarted by a single proctor, Matt Goldie, who happened to have been on the Dinky himself. Only by virtue of his intervention did the 10 departing frosh make good their escape, and the rest of the ugly crowd get broken up.

Now, you might say that was America in the 1870s, the ethos of the Wild West. Look at Lincoln County, New Mexico. Samuel Colt’s Peacemaker, and all that.

Well, Captain Libertarian, it had not always been thus. The very same faculty that in 1878 regarded hazing as more venal than gunplay had, in July 1799 — that is correct, 80 years before — brought three students, who had been found surreptitiously possessing pistols, nothing else, into their meeting, threatened them with immediate expulsion unless they signed a two-paragraph statement essentially declaring themselves venal, self-centered menaces to the country, abjectly apologizing and pledging to spend the remainder of any time in Princeton imitating monks. They unsurprisingly signed.

But in 1925 (the Wild West having been reliably retired), students were being reminded that they should only shoot blanks when celebrating Poler’s Recess, a ritual of blowing off steam by making as much noise as possible before exams; even in jest live ammo would be cause for serious discipline. Honest.

And of course, there’s the Princeton we now know, where even a decorative Civil War musket with no trigger assembly or firing pin requires 15 or 20 forms on file with Public Safety before it can be displayed over your fireplace with great-great-great granddad’s Class of 1881 banner.

What gives? Well, it’s easy to lay this schizophrenia off onto 18th-century pietism, the residual brutality of the Civil War, or the State of New Jersey and its subsequent gun laws, reflecting its transition from agriculture to industry to megalopolis. But I suspect it also reflects developments in psychology and sociology, which raise threats that firearms can represent in a residential community of pressured 20-year-olds; some of the possibilities are pretty grim. I leave that to our august scholars, but also point out that, while a well-written Princetonian op-ed has in the post-Parkland killings discussion advocated arming 32 sworn campus policemen with handguns, no one seems motivated to allow firearms to students, faculty, or administrators.

This is not a universal approach in the U.S. At the University of Texas in Austin, state law now allows anyone with a concealed carry gun permit to do so on campus; resignations of faculty and deans have resulted in no effect. This on a campus that saw the first televised mass murder in the U.S. at the Texas Clock Tower in 1966, with 14 dead and 31 wounded; a new monument to the dead was dedicated only two years ago. Ever obliging, the U.S. House of Representatives in December passed the Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act, which would in effect apply the same Texas non-standards — or those of any other state which were more lax — to Rutgers and Princeton, despite New Jersey law to the contrary. It seems unlikely to pass the Senate, but that’s hardly the point.

As for me, I think back to the times of the most personal stress during my time at Princeton, and certainly intuit a handgun and a box of shells would never have been helpful, and on the other hand might have led to… You might be different, but I can’t imagine how.

Meanwhile, if there’s a Hollywood movie script that’s ripe for a remake, adapted to modern-day institutions and characters, I wish it were something magical like The Tempest (try the great Leslie Nielsen in 1956’s Forbidden Planet), but I have the uncomfortable feeling it’s actually Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Welcome to the ranch.

No responses yet