Rally ’Round the Cannon: Sounds of Unsilence

Will I dig the same things that turn me on as a kid?

Will I look back and say that I wish I hadn’t done what I did?

Will I joke around and still dig those sounds when I grow up to be a man?

— Brian Wilson and Mike Love, 1965

The somewhat controlled avalanche of the Reunions “following” COVID now being in the rearview mirror, it’s rather intriguing to consider the major changes involved in catching up with two missed episodes for the first time since 1946 — a very, very long time ago when 7,000 returnees was a then-unimaginable new record.

But in part via widened support systems like inexpensive dorm spaces as remote as Rider in Lawrenceville, a flotilla of shuttle buses heading off as far as the turnpike in East Brunswick, and the Dinky being fully functional, which doubtless made the difference between purgatory and paradise, in real time as you went about your business it felt strangely like … Reunions. The official attendance record set was “only” 26,000 (dampened by stifling Saturday weather). But the real reason there was not utter chaos was that, while there were more bodies and meetings and symposia and blah, blah, blah, there remained the same number of classes reuning because every class does it every year anyway — 66 classes plus the Old Guard. So the tents may get bigger, the apps may get applier, the alerts even more alert, but basically the moving parts are identifiable, if a bit larger. Which will continue, as disease and travel revert toward normal in support of even larger festivities in years to come. As I’ve often said before, if the classes today cooked up such a multi-megaparty from scratch and proposed it anew, the administration (while being very nice folks on the whole) would laugh us off the planet.

Before we get too far from the superstructure of Reunions, let’s mention a couple important things. The P-rade actually welcomed three new classes at once — 2020, 2021, and 2022 — which was a pile of 3,000 folks on Poe field, but you still only had to sing Old Nassau once, so what the hey. On the opposite end, Dr. Joe Schein ’37 popped in for his seventh Class of 1923 Cane as elder returning alum, and three classes joined the Old Guard luncheon — 1954, 1955, and 1956. You read that correctly: Ralph Nader ’55 and Neil Rudenstine ’56 are now members of the Old Guard. Any Princetonian reaching this point in the story could easily write a column on that morsel alone, so rather than do that I’ll let you imagine your own.

Instead, we’ll focus on the last hurrah of the 65th reunion Class of 1957, prior to joining the Old Guard themselves. At a norm of 87 years old, about half the original class of 700 is still alive, and a generous 71 of them put in a (presumably double vaccinated) appearance. And for the umpteenth time, and most certainly not the last, they faced down, discussed, and debated their unique label, “The Unsilent Generation.” If you’re familiar with their undergraduate era, this sounds snide; if you’re not, it sounds illiterate. It’s certainly a label, still used after 65 years, that requires some backstory and understanding.

Entering Princeton on the heels of the Korean “conflict” and continuing through the first administration and reelection of World War II hero Dwight Eisenhower, their time was overshadowed by the Cold War, tail-gunner Joe McCarthy, the brutal crushing of the Hungarian uprising in 1956, Alger Hiss’ speech on campus, and the stirrings of Black consciousness in the U.S. with Brown v. Board of Education, followed by the outrage at the lynching of Emmett Till in 1955. But much of the power structure, the product of the crucible of the war, as was Eisenhower, didn’t perceive much involvement or comparative pizzazz in the students of the day, and so developed the somewhat mythic characterization of the Silent Generation, which was etched in concrete by Time magazine in a 1951 article highlighting the color-within-the-guidelines proclivities of the youngsters coming of age. By 1957, the image and epithet acquired almost universal acknowledgement.

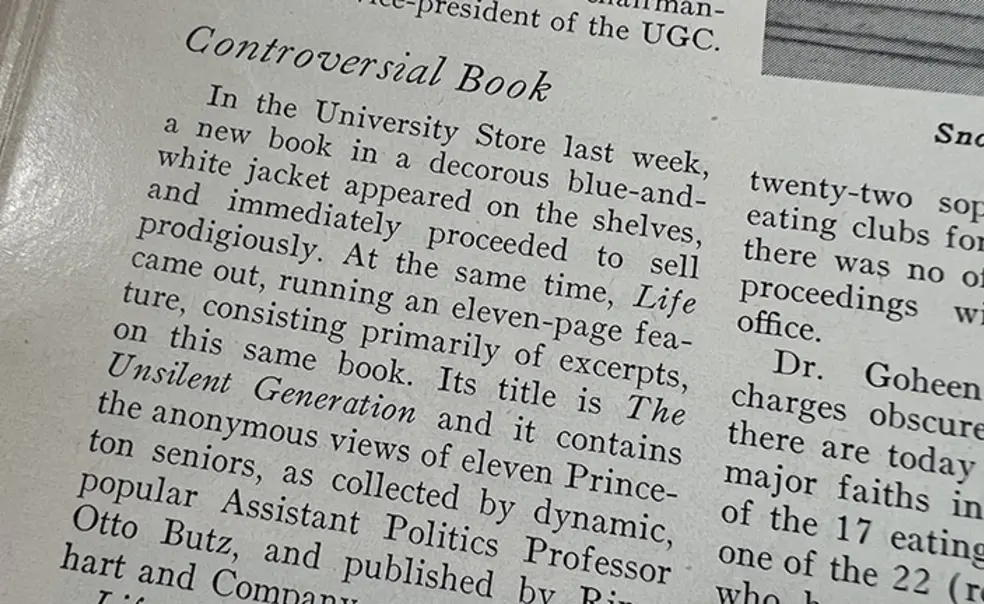

Popular assistant professor of politics Otto Butz was not really pleased with that blanket indictment, based on his precepts with a range of Princetonians. (Of course “the range” was not nearly so broad as today.) He hit upon the idea of simply asking some seemingly aware seniors about their lives — past, present, and future — and letting readers judge for themselves. The folks at Rinehart in New York agreed, 12 Princeton ’57 classmates were chosen to write the essays (one withdrew because of illness), and Butz chose to title the resultant compilation The Unsilent Generation. In the sense that the content did not consciously confront the epithet, that’s a convenient misnomer, helpful only if you wish to sell books — which it did. Life magazine did an 11-page spread, and you will probably find it even more astounding that then-PAWeditor John Davies ’41 personally wrote a five-page deconstruction of the book. He noted that Nassau Hall seemed outraged, but Davies couldn’t fathom why. Alumni letters to the editor, remarkably few in number, were somewhat confused by the hubbub although hardly impressed with the book; the capstone comment came from Bert Lewis 1899, who noted it never occurred to his class as seniors to lay their opinions out there to the world, which probably made them look smarter.

And then came the hatchet job in The New York Times Review of Books that began, “When I was an undergraduate at Dartmouth, we sang a song….” No, really. It went on to critique something the reviewer imagined, which may have been interesting but wasn’t even implied in the book itself. More alumni grumbling ensued.

The timing was awful. PAW reported the book’s publication in February 1958 adjacent to brand-new president Robert Goheen ’40 *48’s initial comments on the just-concluded Dirty Bicker. The trustees ordered knowledgeable student leaders to report to them in person on both issues.

What incendiary, brutal, malicious writing caused such upset? Well, the actual composition of the 11 essays was so good Rinehart demanded to see the original submissions from Butz out of concern he had ghost-written them. What they do reflect (while making no claim to be representative of the class or anything else) is a lot of navel-gazing, nervousness at fitting into the world their elders had created and fought for, and a notable lack of interest in risk-taking or what we today would call entrepreneurial spirit. Which is hardly a sin. Speaking of which, there is hopeless confusion throughout regarding religion and/or ethics, which almost all seem to feel they should regard as important, but can’t even tell apart. (Butz’s choice of four Protestants, three Catholics, and four Jews in this regard is brilliant — they’re barely distinguishable.) Their views regarding women are not so much hopeless as imaginary, betraying not only an all-male campus but a lack of meaningful conversations with their mothers. Their ambivalence about the clubs is obvious, but unexamined. And the supposed Princeton shibboleth of service to others is nowhere to be found except in the case of the buttoned-up classmate who plans to follow his father’s military career. PAW’s On the Campus columnist Reeve Parker ’58 best described the book as analogous to a normal campus dorm bull session, rather than any attempt to solve the world’s ills.

Our late friend Merrell Noden ’78’s fine article on the class 15 years ago noted that the supposedly self-absorbed “Unsilent Generation” in the end included such highly original and uncommon members of society as Dean Determan ’57, Harrison Goldin ’57, and Hodding Carter ’57 in their prolonged efforts supporting civil rights; Norman Augustine ’57 as assistant secretary of the Army; Bob Edwards ’57 as college president of Carleton and Bowdoin; Tom Kean ’57 as New Jersey governor; and one of my personal heroes, Robert Caro ’57, perhaps the greatest writer on politics in American history. This is very much on a par with surrounding Princeton classes, and actually remarkable for an ex-bunch of ’50s 20-year-olds with no meaningful college access to women or racial minorities.

What we should probably glean from this extreme episode really involves packaging, not substance. The Silent Generation moniker was a thoughtless, ignorant label from the first, and meeting it on its own terms with The Unsilent Generation title was a dismal mistake at the outset, whether by Rinehart to sell books or Butz to jerk the adults around. (He certainly improved his getting-along skills, eventually spending an honored 22 years as the seminal president of Golden Gate University.) In glibly setting up the necessarily immature (if well-expressed) thoughts of those 11 men as somehow corrective of the generation gap between them and their World War II predecessors, it did a disservice to both, even if it did generate a sure-fire nickname for the class and its reunions for the next 65 years (and counting).

No responses yet