A fire with water we defeat,

With parasols the midday heat,

Mad elephants with goads that prick,

Oxen and asses with a stick …

Science has cures for every ill,

Except the fool; he prospers still.

— From the Sanskrit, quoted by Dr. Wilder Penfield 1913

There is a vocal subset of the loyal Rally Fan Club — didn’t know five people could have a subset, did you? — that would be very happy if we never discussed anything but athletics. Inspiring performances such as this winter’s triumphs by the astounding Fred Samara’s men’s track and field squad and the inspirational Courtney Banghart’s overachieving basketballers (with a huge credit to co-captains Tia Waledji ’18 and Leslie Robinson ’18) just turn up the heat. The mounds of good content on goprincetontigers.com, including the exemplary TigerBlog of Jerry Price, would sate most reasonable appetites, but noooo …

So, in the interests of eventually getting along with life beyond Jadwin Gym, and to calm the hysterical group who are still outraged Bill Bradley ’65 was not named one of the 25 most currently influential Princetonians, I’ve agreed to do a quickie sports quiz here at the top to calm things down:

- Who was the only Princeton football head coach named on the original 2008 list of 250 most influential Princetonians of all time?

- Who is the only Princeton head football coach with his own Google Doodle? (No, Eric Schmidt ’76 was not the head coach …)

- Who is the only Princeton head football coach named in Philip K. Dick’s fiction masterpiece Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Think Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049.)

I see that the queue of those suspicious they’ve been duped already reaches around the virtual block, so let me hasten to note this is entirely legitimate, these are not trick questions, and — big hint — they all have the same answer. Got it now? Of course you knew, just had to stretch those little gray cells a bit.

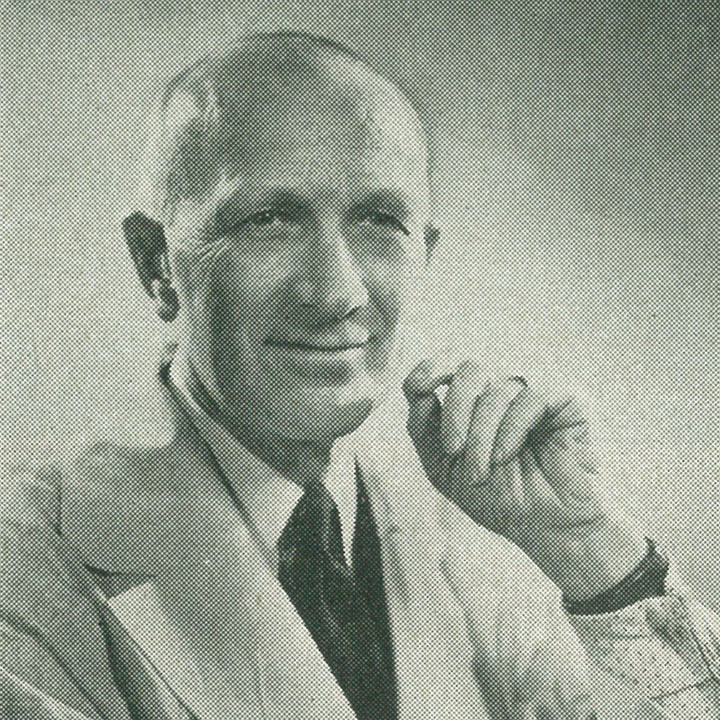

Which is also a big clue in itself, because the right answer is, just for good measure, one of the most beloved Canadians of all time, Wilder Penfield 1913. In a way, he was also a forerunner in the medical world of the approachable, humanistic genius, just before the media came of age in time to create Dr. Benjamin Spock, Dr. T. Berry Brazleton ’40, and then begin to avail itself of less-talented, more-narcissistic medical wannabes who pervade the Twitterscape today.

But make no mistake, Wilder Penfield was the real deal. From Wisconsin, desirous of eventually studying at Oxford and needing a Rhodes scholarship to do it but buried far down the depth chart on his freshman football team, he took up wrestling for the first time and eventually built himself into a 170-pound (if cerebral) starting tackle for the varsity, blocking for Hobey Baker 1914. Arriving at Princeton a year after the legendary Edwin Grant Conklin to formed the biology department in Guyot Hall, Penfield was bitten by the science bug despite his father’s failed career in medicine and made it his life’s passion. After his first attempt at a Rhodes fell short, he coached the football team to a 5-2-1 season in 1914, the year after Baker left, then succeeded on his second Rhodes try and went to study with the world’s pre-eminent neurophysiologist, Sir Charles Sherrington.Back in America after four years in Britain, Penfield turned to neurosurgery as a vehicle toward further exploration and moved quickly to the forefront of the field. While co-writing Cytology and Cellular Pathology of the Nervous System with his partner Dr. William Cone at Presbyterian Hospital in New York, he realized that, analogous to a football team, the book would be far superior if a specialist wrote each chapter. He and Cone acted as editors and guides. Further, it occurred to him that research in neurophysiology would be best done the same way, with an integrated team of scientists, physicians, surgeons, and technicians dedicated to a common goal. Not seeing an immediate future for this model in the U.S., he took the opportunity in 1928 to move to McGill University in Montreal, which became his base for the rest of his life. He pitched the then-revolutionary concept of a medical research institute to the Rockefeller Foundation, and in the middle of the depression it came up with $1.2 million — a then-gigantic sum — to fund the Montreal Neurological Institute in 1934. It took little time for Penfield to begin attracting the best young researchers and surgeons from around the world and begin revolutionary advances in brain studies, including the first mapping of various regions and their specialized functions. Only three years later he was addressing the gathering at Alumni Day in Princeton, in a talk (including the sage words to bothersome alums above) that would become reprinted and discussed for decades. Two years after that he received an honorary Princeton Ph.D., the first of dozens of awards from everywhere. “A strong and gentle man,” the citation notes, “with dexterity he penetrates the recesses of the human brain and restores to lives of usefulness and happiness those who had been facing the future without a single ray of hope.”

Along the way, he realized vital clues to the workings of the brain could be gleaned if the patient were awake during surgery, with only local anesthetia (“the Montreal Procedure”); needless to say, this created a sensation. He and his wife became Canadian citizens out of gratitude to their adopted country. He traveled the globe, consulted on neurosurgery during World War II in England, China, and Russia, and afterward India, France, seemingly anywhere; he not only received multiple awards in Canada and the Medal of Freedom in the U.S., but the French Legion of Honor, honorary membership in the Soviet Academy of Sciences, and in Britain, the Order of Merit, which honors no more than 24 living people. He was a Member of the Royal Society, and the only two-time president of the American Neurological Association.

Firmly believing that every life needed a substantial second career to keep the brain sharp, at age 63 in 1954 he quit virtually all his responsibilities at the Montreal Institute and took up writing. He began with two novels, including the rework of one begun by his late mother decades before, and one about Hippocrates. He also spent time speaking about his prior career; the importance of having a second one ready to go when you’re still fit and able; and the importance of the family and home education in the psychology of children, including the great advantages of multilingualism, especially when begun early. He created his second institute, the Vanier Institute for the Family, when he was 74 years old.

His accessibility and indefatigable sense of service and joy in humanity, paired with his singular insights into the brain, led him to become a household name in all sorts of surprising ways. During the early ’60s, on a CBC discussion program somebody referred to Penfield as the “greatest living Canadian”; it stuck somehow. When Bill McCleery, the great teacher, playwright and chronicler of Princeton, went to Montreal to interview Penfield in 1965, he drove across the border in some remote location, and the Canadian customs officer asked him why he was there. Told McCleery was to interview Penfield in Montreal, she proceeded to praise the doctor, refer to his medical and personal virtues as if they were next-door neighbors, and tell McCleery how intelligent he was to see the importance of such a task. In his 1968 novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the sci-fi legend Philip K. Dick created the Penfield Mood Organ, a hazily described means to plug in electronically and alter your mental attitude. Using Penfield’s name was a clever, and most effective, way to reinforce the real question of the tale: What does it mean to be human?

Which brings us back to Penfield’s 1937 address at Alumni Day, which is intriguingly poignant, humorous, and an intellectual tour de force all at once. The topic, presumably requested by the Alumni Association, was: What Good Is an Old Grad? Amazingly, he began the talk with Charlemagne, then to Bologna in the Middle Ages, tracing the entire history of Western universities and the forces behind them, pointing out that alums were barely a thing until American colleges made them one very late in the game. His advice to alumni busybodies? Be sure to raise your own kids well at home according to the wisdom you learned in college; and provide resources, allowing your institution to transform them into the “scholarly hope of enlightenment, without which these modern times would indeed be depressing.”

Considering that vision and the rest of his astonishing life, it was no wonder that the Class of 1913 in its 1976 memorial noted that “to him was given the talent of inspiring others to greater achievements and nobler living.”

Not too shabby for a 170-pound tackle.

No responses yet