Rally ’Round the Cannon: Yoshio Osawa ’25

As you read this, the Class of 2025 will be getting their old selves stored away, driving their moms crazy, and deciding what to pack as they travel to their new lives in “residential colleges” (whatever those are) and deep in the bowels of Firestone’s looming C floor.

I mention this in part to note their great-great-grandparent Class of 1925 now faces the dark passage in which their numerals expand from two to four, as in “the late Lew Mack 1925” or whomever. When we last left the old Class of ’25, we really left them — it was in 2012, to honor the death of their last classmate, Malcolm Warnock ’25, who won the 1923 Cane at the P-rade eight times. They never got to use Firestone, which in fact they needed desperately as the volumes spilled out of Pyne Library and into every dim cranny on campus. With 581 members, they were the largest class ever to matriculate at Princeton. They included such widely varied notables as George Kennan, the honored statesman and writer on international affairs; Paul Swain Havens, long the president of Wilson College in Pennsylvania (not named for Woodrow 1879, by the way); and the irrepressible Charlie Caldwell, Hall of Fame coach and to this day holder of the longest football winning streak in Princeton history at 24 games.

We visit the class again today, both in honor of 2025 and in response to another of those intriguing inquiries to our friends the Princetoniana Committee, courtesy today of Terry Rosen who asks the following: Whazzat?

Late last year, Rosen brought this scarf to the committee, which fell instantly into a two-pronged attack. The linguistic crowd quickly found the Asian script (Japanese) translates roughly to “Princeton Tenth Anniversary” or a close version of the English, and the implication there was a Japanese flavor to the class reunion activities. Meanwhile, the relic-focused crowd tried to come up with some sort of backstory to the Class of 1925’s Japanese theme (if indeed it was one) and what it might be doing at Princeton Reunions four years after the Empire of Japan wrested Manchuria from the internally conflicted Chinese.

The answer was, for a refreshing change, unambiguous and straightforward. And he had a name, too: Yoshio Osawa ’25 of Kyoto, Japan.

Even among various periods of xenophobic wingnuttia and Americans’ legendary obliviousness to other cultures, relations with Japan have always been different from other places, including those in Asia. Beginning with the “opening” of feudal Japan by Commodore Perry in 1854, that nation decided to face the rest of the globe on the globe’s own terms, and its adoption of many Western behaviors aligned to a Princeton worldview that began to expand via president James McCosh’s arrival from Scotland in 1868, coincident with the beginning of the Meiji Restoration. The ever-magical April Armstrong *14 relates in the Mudd Manuscript Library Blog the tale of Rioge Koe 1874 of Japan literally surrendering his sword to McCosh in June 1873 in recognition of his conversion to Christianity. His presence wasn’t an anomaly, as there were three other Japanese students here during his time on campus. She also tells of the first Ph.D. awarded to a Japanese student, in economics to Bunshiro Hatton *1906, who found the English required for his thesis to be far more challenging than the mathematical modeling.

In the meantime, the Japanese empire built a powerful armed economy based on the recent German constitution and centered around family industries, and in 1902, Osawa’s father founded J. Osawa & Co. as an international trading company. Looking ahead to trade with the West, he sent his son to the Lawrenceville School for two years of English polishing in 1919, following corporate success during World War I on the side of the Allies. Arriving at Princeton with the Class of ’25, Osawa quickly gained friends. He ran track, debated at Whig, and was described in his PAW memorial as one of the best-liked men in the class.

He immediately then went to work for his father, and by 1932 also started the first talking picture studio company in Japan as a subsidiary. It merged in 1937 with Toho, the largest movie producer and distributor in Japan, and Osawa became a member of the board. He eventually became president of both the trading and huge integrated film companies.

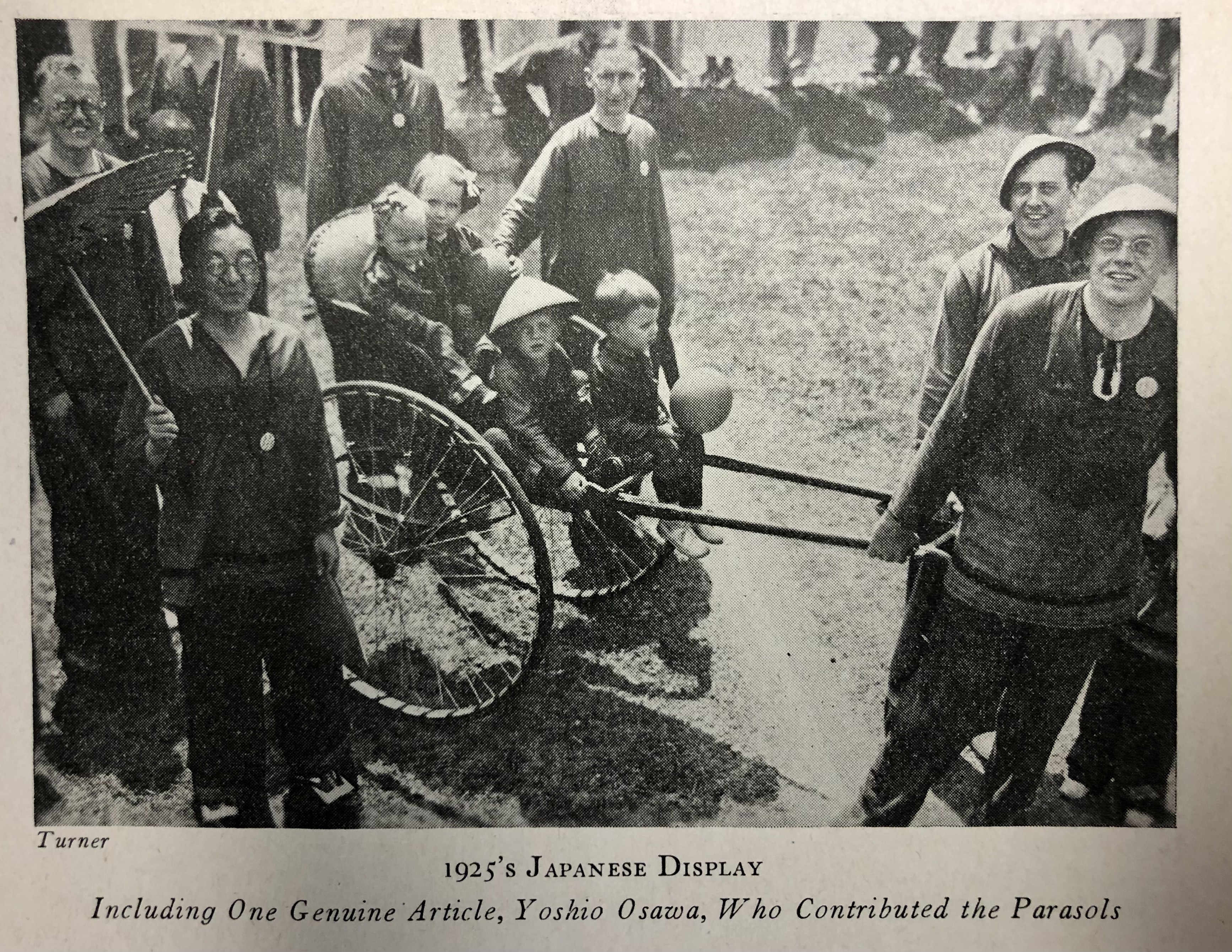

Meanwhile came the 10th reunion of the Class of 1925, in the middle of the Depression and the gathering of fascist and militarist regimes across the globe. In the teeth of this, the class decided to go all-out on a Japanese P-rade theme, complete with orange-and-black parasols and Rosen’s scarves (ah-HA!) supplied by J. Osawa & Company courtesy of Osawa. The outfits actually got written up in the New York press, and ’25 had the largest official attendance of any class in history at 230.

When he was invited, to huge acclaim, to say a few words to the class in thanks for his long-distance award, Osawa proclaimed his gratitude and invited the entire class to join him for a repeat performance in Japan. This was not said in irony, and there is no indication it was taken that way; even in a Depression, age 32 is not a time in life when ironies abound.

As friction between Japan and its neighbors increased and the military asserted itself, Toho as the nation’s largest studio was pulled into propaganda films rather than be liquidated. (We should note many U.S. studios did the same.) Osawa had enough cover to continue his more artistic interests on the side, for example nurturing the first films of the famed Akira Kurosawa. After V-J Day, Osawa was tried along with 5,000 or so others as “Class B” criminals for their activities in support of the state during the war, and removed from power during the American occupation. He was restored just as he sent his son to Lawrenceville in 1951, in preparation for Princeton’s Class of ’57. In 1954, Toho released Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai, and the company’s business moved back into the international mainstream. It also unleashed Godzilla, borrowing from both King Kong and the nuclear fallout of the war, and Toho’s long-term financial success was assured; it remains Japan’s largest film company to this day. A year later, Osawa called class president Charlie Caldwell, and 10 years following Hiroshima and Nagasaki, repeated the invitation for the class to come to Japan.

On May 14, 1956, 18 classmates and their families arrived in Tokyo and spent eight days of astonishing cultural tourism under the guidance and planning of Osawa and the shepherding of Caldwell, including Kabuki, geisha, sumo, a reception at the U.S. embassy, and traveling 1,500 miles by train, plane, and bus with sightseeing, receptions, and parties at every turn. Osawa’s wife Tazuko presented the class with custom Happi coats festooned with tigers to wear over their blazers.

And, oh yes, Osawa appropriated a film crew from the studio and documented everything via a 23-minute professional-movie (credited as “A ‘Seaweed’ Osawa Production,” using his nickname going back to undergraduate days), along with a four-page spread in PAW, this was likely the best-documented mini-reunion in Princeton history. There was coverage in both Time and Life magazines. In Osawa’s name, the class established a scholarship for Japanese students at Princeton. The ’25-Princeton Club of Japan gala (shown in the movie) was also the kick-off for a big drive by the club to revive itself, including the establishment in 1958 of the Osawa Fellowships, which bring Princeton students to Japan each summer.

Now, this is a good story with an upbeat ending, and very much in tune with our “Princeton in the Service of Humanity” extrapolation of the University’s informal motto. Its context in and around the cataclysmic brutality of World War II in the Pacific elevates it to borderline miraculous, a clear triumph of personal understanding and compassion over deep wounds and great pain. I’m not sure, with the Class of 1925 gone, that we have the fortitude to similarly face such lessons and bring them fully to bear on the stupidly longstanding proclivity of Americans to mistreat and belittle Asians, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. But perhaps, if 1925’s great-great-grandchild class, newly gathered and ready to grow, were to watch Osawa’s movie and hear the tale themselves, it might be a start.

It may be very telling as well that the applicable proverb comes neither from the U.S. nor from Japan, but from China: “The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

1 Response

Staughton Yoshio Lewis ’93, Secretary, Princeton Club of Japan

4 Years AgoThank You from Tokyo

On behalf of the Princeton Club of Japan, the club's advisory board, and all Japan alumni, I would like to extend our sincere gratitude and thanks for the research and publication of this article. Although geographically apart, the Princeton Japan alumni truly feel accepted and are proud to have a place at the table in the Princeton University and Princeton Alumni community.

Tiger Cheers,