Rally ’Round the Cannon: You say you want a revolution?

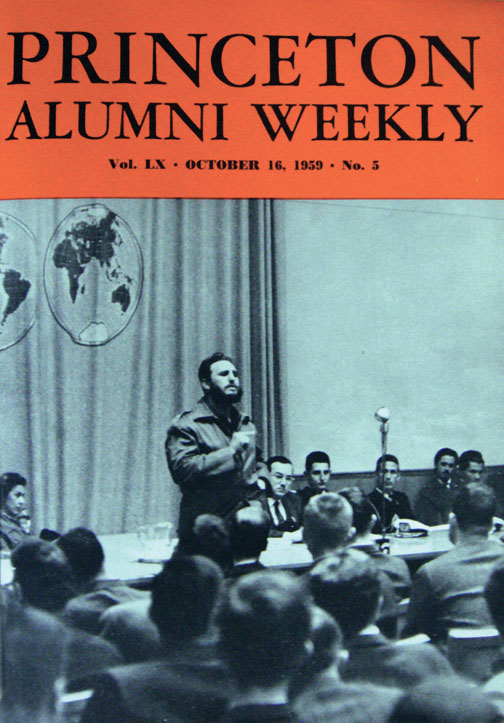

Fidel Castro’s 1959 visit to Princeton created a media circus

History is a funny thing. Not funny-haha necessarily, although Woody Allen’s film Bananas is a pretty useful window into Americans’ understanding of Latin America in the mid-20th century, but certainly funny-peculiar.

For one thing, the seeming currency of a given event doesn’t relate at all to its removal from us. (Time for another bow to Dr. Einstein and his profound observation that time is relative.) Current happenings create little wormholes that catapult us back to, say, the Great Depression (can’t imagine why that came to mind ...) or Wilson’s Fourteen Points as if we were there, while much more recent happenings – the marvelously named Laffer Curve, for example – feel as remote as the Roman Empire. Now, that was a government that knew how to broaden the tax base, if not Laff.

We owe a great debt to Latin American studies professor Thomas Bogenschild, now at the University of New Mexico, for piecing together in 1998 the story of the occasion (perhaps “close encounter” would be more accurate) in a rational way. So much happened, much of it spontaneous, in such a short time in such a charged atmosphere that contemporary accounts might have been written by Woody Allen; at least the plot would have been clear. The highlights:

Roland Ely ’46, who lived in Princeton and was an expert on Cuba as well as a sympathetic cousin of a Castro insider, was the driving force behind the local visit, strategically placed between Washington, D.C. (Meet the Press, Vice President Richard Nixon) and New York (the U.N.) on the new regime’s goodwill tour of the United States following its takeover in Havana. The Princeton historian whose seminar Castro ostensibly was coming to address served as more of a convenient front. The only faculty expert on Latin America, professor Dana Munro, was included as an afterthought. Ely gave interviews and styled himself a “citizen ambassador.”

As the new Cuban government rapidly metamorphosed after its triumph, the tenor of the impending trip became more charged in the surrounding Cold War atmosphere, although Castro still espoused democracy. The University, whose most challenging breaking news event at the time probably was Dick Kazmaier’s 1951 Heisman Trophy, was faced with 24 hours of unpredictable multilingual assault as a large delegation of Fidelistas and the world press cartwheeled through town. The initial strategy was to issue no press guidance at all, pretend the event was private, and forbid the press from attending the seminar.

The New York PR firm hired by the Cubans, betraying even more wishful thinking than the Princeton administration, recommended the revolutionaries shave their beards and wear suits on the trip.

In what has to qualify as Prospect street’s most culture-bending episode until the day the Third World Center opened, 29 Cuban journalists in the Castro entourage stayed overnight at Cottage. Presumably, they were not required to wear black tie at dinner.

The seminar in Corwin Hall was a complete circus even before it started. The Cuban journalists (now well-fed) couldn’t be kept out, and they insisted the American journalists lurking outside be let in. They were. There were so many distractions that no complete record of Castro’s ramble on “The United States and the Revolutionary Spirit” exists, and it’s even unclear how long he spoke, although two-and-a-half hours seems a good guess. He did say “there is little room in Cuba for communist ideas.”

The post-event reception was held by New Jersey Gov. Robert Meyner at Morven, then the governor’s mansion. The Cubans left quite a few cigar butts on the landmark’s floor.

Then it was on to New York and further spontaneous adventures for Castro and his merry band at the United Nations, Central Park, and various surprise stops around town. The New York Times headline four days later was “Castro Departs to Joy of Police.”

There were also some significant lessons learned by Princeton, in the honored tradition that whatever doesn’t fire artillery at, or burn down, Nassau Hall makes you stronger. Certainly the press relations got a thorough review; even if President Bob Goheen ’40 *48 didn’t foresee the wildness of the ’60s, he certainly did see a more dynamic University taking shape, one that would have to deal with the wider world far better than the “no-comment” approach. And it’s difficult to believe that any private alumni have subsequently booked a head of government into an on-campus speaking engagement without prior clearance and central oversight. By 1966, there was also a formal Program in Latin American Studies, headed by Munro. If ignorance is bliss, then the handling of Castro in retrospect was Nirvana.

A little event-handling improvement also would come in handy sooner than most expected; less than a year after Fidel Castro caught the 10:10 special to New York, the great dean of the chapel, Ernest Gordon, judged the time to be right to introduce another cutting-edge message-bearer to the Ivy-covered enclave. He invited Martin Luther King Jr. to give the Sunday Chapel sermon. But that’s another tale.

Some folks, however, don’t see turmoil as a potential learning experience, just a threat: 728 days after Fidel Castro browbeat his amazed audience in Corwin Hall, the United States invaded Cuba.

No responses yet