Ralph Nader ’55’s Paradise Lost

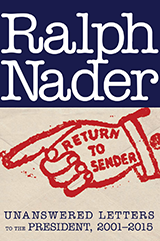

In his new book, Return to Sender: Unanswered Letters to the President, 2001-2015, consumer advocate Ralph Nader ’55 attempts to hold presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama accountable for their campaign promises.

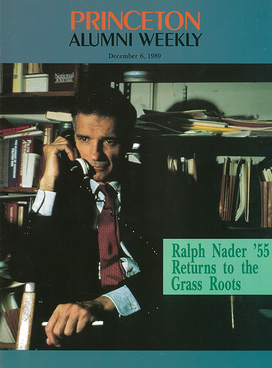

In 1989, PAW ran a profile of Nader that described him as “a legend, perhaps the only universally recognized symbol of pure honesty and clean energy left.” The story, by Marc Fisher ’80, is reproduced below.

A LOT OF what you thought you knew about Ralph Nader is wrong. Those four dozen pairs of socks he bought at a PX in the fifties to last a lifetime? They wore out a decade ago, and he went and bought a bunch of new ones. He follows the N.B.A He is not humorless, far from it. He did not disappear because he had a stroke. He does too have a driver’s license and even occasionally gets behind the wheel. He does not live in an $80-a-month room near Washington’s Dupont Circle. He is not nearly as interested in car safety as he is in the total restructuring of the American economy and society. He does too read novels, three times a year; the last was Day of the Jackal, the spy thriller.

A lot of what you thought you knew about Ralph Nader is right. He wears goofy, indestructible black clodhoppers. He carries in his memory more dramatic, damning statistics than would fit in the entire opus of the Harper’s Index. He travels the nation with a battered, torn, old vinyl briefcase packed to the gills with documents, proof that corporations have done wrong and government has failed us. He is uncomfortably shy. Out of some combination of shyness and arrogance, he can barely bring himself to use the word “I.” He is oblivious to pop culture. He asks questions about everything he eats. He has less tolerance for chitchat than the average 411 operator. His articles and books are saturated with the words “should” and “must.” He lives his work every waking moment, freely dispensing unsolicited advice to total strangers.

Ralph Nader is a legend, perhaps the only universally recognized symbol of pure honesty and clean energy left in a culture that, after being shot through with greed, cynicism, and weariness, is oddly proud of itself. Twenty-five years after he slew General Motors, Nader, the young dynamo who could not be bought, is a reminder of what we once hoped to be.

He is a strange man. Even close friends don’t know where he lives. He insists on being the last to board a plane. He won’t visit friends who have house pets. Once his oddities made him cool. He fought G.M. but didn’t own a car. He made rhetorical chopped liver of overblown corporate executives, but stayed as far outside the American consumer economy as one could be.

Then he vanished. Oh, he was still there, right on P Street, toiling away till all hours in his densely packed basement office, surrounded by cardboard boxes, young aides ready to find any fact, and the documents, always the documents. But these were the Reagan years, and people just didn’t want to hear it. Not the President, not Congress, not even Nader’s old friend and sturdy tool, the press. Truth be told, the people didn’t want to hear Nader’s carping and whining either. Everyone knew he was right. That was a given. All the same, the message came through: Lighten up, Ralph. Save the whole grains; have a steak.

To make matters worse, in 1986, Nader fell victim to Bell’s palsy, a disease that that froze one side of his face and made him look like he’d been drinking. He would appear on television, and people would think he’d had a stroke. The disease, caused in part by stress, forced Nader to drop from sight for a time — but only after he had another compelling reason.

That summer, Nader’s older brother, Shafeek, was dying of cancer. Shafeek was the only one of the four Nader kids to stay home, in Winsted, Connecticut, where he led and won the fight to create a Winsted community college. His death that summer made Ralph Nader do something he had not done in more than twenty years: He stopped.

He spent weeks with his parents. He reconsidered his life. And when he returned to P Street, co-workers say, his approach had shifted. His values and goals were unchanged, but now Nader seemed determined to focus his energy. “When Shaf died, Ralph decided he couldn’t be Johnny Appleseed anymore and work on dozens of issues and organizations at a time,” says Joan Claybrook, a friend since 1966 and president of Public Citizen, the umbrella for many Nader groups. “It hit Ralph how fragile our existence on earth is. He had to focus on a few issues and make his impact.”

When Nader resumed his activities, his face was almost back to normal — there is still a twitch on the left side, and his eye gushes with tears when he eats. For the first time in his life, Nader seemed concerned about how he looked; co-workers say that Nader suddenly took to wearing sharper suits and more stylish eyeglasses. But the Washington he returned to did not welcome Nader home. In the waning years of the Reagan Administration, Nader wrote reports and nobody did anything. In the past four years, Nader’s groups have held twenty press conferences to release new studies, and, he says, the Washington Post bothered to send a reporter all of once. When he lobbied with his usual zeal, the boys on the Hill told him to PAC up and take his act elsewhere.

Now, as the nation slowly wakes from its long and rather pleasant dream, Nader has done just that. His loose network of public-interest groups continues to dog the government and use the courts to fight for better water, medicine, food, cars, household products, and all manner of other causes. But with his usual outrage (he gets especially piqued at the notion that he has vanished and reemerged), Nader has turned his back on Washington, where the jaded media ignore him, away from the federal government, which has disappointed him gravely, and out to the grass roots, where he has always had his finest moments.

OUT THERE in that proverbial beyond that begins where Washington’s rush hour ends, Nader found the wellspring of support for his populist battle against the Congressional pay raise last year. Out there, Nader broke one of his lifelong rules and took to the hustings, campaigning in California for Proposition 103, an automobile-insurance-rate rollback for which Nader made TV spots and appeared at old-fashioned rallies. Out there — together with many of the more than eight thousand lawyers, researchers, and volunteers who have worked for groups he created or inspired — he fought new battles to create citizen groups to represent ratepayers in the regulation of utility companies, to stop apple growers from using the chemical Alar, to organize consumers who share complaints about product defects.

If the old allies weren’t playing ball, Nader found new ones. Under Reagan and “his government of the Exxons, by the General Motors, and for the DuPonts,” Nader said that consumer groups had “to place more emphasis on what can be done at the the state and local levels.” Nader groups lobbied state attorneys general to file suits on all-terrain vehicles and health claims in Campbell’s Soup ads.

To fight the pay raise, he teamed up with a guru of the New Right, Paul Weyrich, and a nationwide network of wild-mouthed radio talk-show hosts to send Congress and much of the Washington Establishment mumbling and seething to defeat. “The incongruity of the matchup certainly got people’s attention,” says Bill Kling, the spokesman for Weyrich’s Coalitions for America. “Paul and Nader disagree on almost everything else. But they agreed that the way to move Congress these days is to set up grass-roots opposition against the official reaction in Washington.”

Away from the capital, Nader found that the old allies were still friends. He held press conferences, and reporters packed the rooms. He issued studies, and local and state governments hustled to do something before the Nader-initiated public rage was visited upon them.

“We’re fighting discouragement,” Nader says. “When was the last time we solved any national problem? The only one I can think of is traffic safety. That’s why Prop. 103 was so important. It showed that problems can be resolved if citizens take action.”

“You guys in the Washington press are tired of Nader, and I don’t blame you. But when Ralph Nader walks into a Salt Lake City or a Denver, the radio and TV talk-shows are falling all over themselves to get him.” That’s Scott Carpenter speaking. He should know. For eight months last year, he helped run the insurance industry’s campaign against Prop. 103. The industry spent a mint — a national record $70 million — on that campaign. Harvey Rosenfield’s Voter Revolt group spent $2 million and nuked Goliath with one simple weapon — Nader.

“The magic of Nader is to get the mass media onto something,” Carpenter says. “With his groups around the country, the students in the Public Interest Research Groups, he has an army of people out there. You could find some negatives on Ralph Nader. But we couldn’t attack him because who would listen to insurance companies saying bad things about him? The only thing we could try to do was change the shorthand identification from the ‘Nader initiative’ to the ‘Rosenfield initiative.’”

The insurance industry plastered California with ads that named Prop. 103 after Rosenfield, a cheerful little guy who has worked for Nader since he was in law school. The anti-103 ads attacked Rosenfield, mispronouncing his name, trying to make him sound like an extremist. But they never mentioned Nader. The ads didn’t work. Despite the awesome gap in funding, the rollback won with 51 percent of the vote.

A California Poll taken at the start of the campaign showed that if voters knew absolutely nothing about a ballot initiative other than that Ralph Nader was for it, 67 percent of them would be inclined to vote yes. The comparable figure for insurance companies was 13 percent.

“It was the first time he had done campaigning, but we finally got him out here for six straight days,” says Rosenfield. “And it was amazing. We couldn’t afford signs, but we’d go to rallies, and people would have homemade posters that just said ‘Nader 103.’ That’s all people needed to know. He was the critical factor. The insurance commissioner said that being criticized by Ralph Nader is like being criticized by Mother Teresa.”

HE MIGHT as well be Moses, judging from the reception he gets on the road. Nader has always taken his message directly to the people, to inspire support and for the cash he gets from groups that hire him to speak. Virtually all the money he takes in is pumped back into his Center for the Study of Responsive Law, a fancy name for the dozen lawyers and students who work directly for Nader at his traditionally pathetic wages. (Lawyers who toil for Public Citizen and the other, larger Nader groups that he no longer runs directly have considerably better working conditions. A starting lawyer at Public Citizen now makes $21,000 a year, more than twice what Nader himself claims to live on.)

At California State University at Northridge, more than two thousand people have turned out to hear Nader. They gawk at him, and he shies away. They step up and don’t quite know what to say: “I’m a fan, even though I drive a Chevy,’’ one man says. Nader just smiles. He sits down to wait his tum to speak, and manages to hide his slim, almost concave six-foot-four build, virtually folding himself into a chair.

It is mostly an old crowd, drawn by promise of a talk on health. Nader, balding these days, his famous black curls now nearly white at the temples, is introduced by a doctor: “He has maintained his purity and hasn’t sold out to anybody.” The applause is thunderous.

Nader’s lecture is a call to arms, a tirade against the evil of corporate power and an evangelical entreaty for citizens to do something. “It all starts with us. We’re the ones that create shelf space for All Bran and low-salt foods. We should all march in to the supermarket manager and tell him what we want.” He rails against advertising, pesticides, cigarette makers, the A.M.A., and the federal government. The heroes of a Nader speech are consumers, advocates, reporters, and, above all, lawyers — the people who file the suits that nail companies and governments for their misdeeds. Nader may be the only man in America who can get audiences to applaud lawyers.

Nader does this routine about thirty times a year — a far cry from the seventies, when he delivered 150 and more speeches every year. He still packs the house, but the older crowds are the most sympathetic. Nader seems to have missed a generation of Americans. When he appears on campuses, many students have no idea who he is. Walking through airports, middle-aged and older folks do double takes. Young people walk on by.

Getting off a short flight from San Diego to Los Angeles, Nader passes a young woman showing her friend a shoe that had come apart at its sole. Nader stops, leans over, and says, “Cheap shoes, huh? You know, they could make shoes that last, but consumers have to demand it.” The woman stares at Nader as if he were a nut, turns back to her friend, and resumes her conversation.

None of this matters to Nader; he does not act as he does to show that he is Ralph Nader. He acts as he believes everyone should. At a restaurant in Los Angeles, Nader peruses a menu while the other five people at the table order. When it is his turn, he locks the waitress in his hard stare and quietly says, “Now I am going to ask you a question, and you probably won’t know the answer. But it is very important.”

The harried waitress, her body already pointed to the next table, says, “Okay.”

“Is the tuna packed overseas or here?” Nader asks. “Because the sanitation is very different.” The waitress goes to find out. She returns from the kitchen several minutes later and announces that she has checked the can. “It says ‘Product of Thailand.’”

“Let’s skip that then,” Nader replies. “Very bad sanitation in packing plants there.” The waitress, who is in her twenties, has no idea who Nader is. “I figured he was one of those people who is a little crazy about what they eat,” she says later. “In this place, you get them all the time.”

Nader had two missions: teach the waitress that consumers can and will question their treatment, and get the information he needed to protect himself from a health risk he was unwilling to take. He does this in many of life’s little moments. He is forever asking people who have volunteered to drive him around to turn off their air conditioning; invariably, they comply. When he meets the children of friends or takes on young volunteers in his office, he often gives them reading assignments, generally from the classics of literature and history.

This sort of attitude comes naturally to someone who once took five courses and audited five more as an undergraduate. His hard-core study habits cast him as an outsider at Princeton, but Nader seems to have been more interested in getting an education than in fitting into what he perceived as a conformist and anti-intellectual student body. Nader graduated magna cum laude, with a double major in economics and the Woodrow Wilson School, and then attended Harvard Law School. For Nader, every encounter in life is a chance to learn something, teach a lesson, or find a source of evil.

THOSE WHO have known Nader the longest say that the most remarkable thing about him is his consistency. He still works like a dog, hates to spend money, calls people after midnight as if it were normal business hours, has a teenager’s sense of outrage, has little tolerance or understanding of other people’s private lives. And he is still absolutely certain of himself. At lunch one day, Nader is expounding on efforts to curb the use of pesticides. He tells Joan Claybrook that Public Citizen needs more lawyers on the issue.

“We have three and a half people on pesticides,” Claybrook protests.

“What about tobacco — none there,” Nader grumbles.

“Not true. We have people on tobacco. You want us to work more on tobacco?”

“Yes, 400,000 deaths a year.’’

Claybrook: “No, 120,000.”

“No, 400,000,” Nader replies, not raising his voice, not looking at Claybrook, just staring at his eggplant, annoyed that he has to defend his facts.

Claybrook, exasperated, puts down her fork and says, “That’s lung-cancer deaths. It’s 120,000 from tobacco.”

“No,” Nader says, his words now clipped and cool. “Surgeon General’s report, 1988. Deaths from tobacco, cancer, and other diseases.”

Claybrook bows out. No one at the table says a word for some time. Finally, someone changes the subject.

“More than anybody else I’ve ever known, his strengths are his weaknesses,” says Bill Schultz, a Public Citizen lawyer who has worked with Nader since 1976. “His values and his style are what give him credibility outside Washington, and what lost him credibility inside Washington.’’

Still, the volunteers come. Still, lawyers agree to work for little money and insane hours, driven by a boss who fails to comprehend the need for weekends or vacations and who watches over every penny. When Schultz once went to Chicago to take a deposition in a lawsuit, the bill for a transcript of the interview landed on Nader’s desk. The legal stenographer had charged by the page, as is customary, and the total price was exorbitant Nader knew he could not tell the lawyer not to take a crucial deposition, so this is the note Schultz received: “These deposition costs are outrageous. From now on, ask shorter questions.’’

Even those who have worked with Nader for many years and admire him greatly say that he has some strange ways. Ever since General Motors hired a private eye to spy on him during the 1966 battle over automobile safety, Nader has been obsessed with secrecy. No one — not even lawyers who have worked for him for decades — gets his home phone number. He refuses to say exactly where he lives, though he concedes that his $200-a-month apartment is near the now demolished Dupont Circle rooming house in which he stayed for many years. Co-workers who have given him rides home say that he asks to be let out at the comer of Connecticut and Florida avenues, N.W.

No one but Nader knows his daily schedule. He travels under false names and denies it. When I found him listed at a hotel as S. Nader and then saw his airline ticket made out to A. Nader, I asked what was going on. “Nothing,” Nader said. “The frequent-flyer people got the name wrong, so I just left it that way.” Staff members confirm that he almost always uses false names or initials in his travels.

But Nader has changed, especially since his devastating summer of 1986. “It used to be he had little tolerance for people who got married,” says Rosenfield, who has worked with Nader since 1979. “Now, in a father-like way, he encourages people to have families.” Indeed, Nader recently told Rosenfield, “Don’t ever be 50 and not have children.”

Nader is 55, has never married, and — despite occasional rumors of relationships with Claybrook and other female co-workers over the years — appears to channel whatever sexual energy he may have into his all-night work and study binges. Claybrook says Nader is great fun to be around, but she also repeats his standard argument that he is simply too busy for romance. Nader did not date in high school, his yearbook dubbed him a “woman hater,” and friends say that they know of no serious intimate relationship in his past.

Nader says he has no regrets. He draws satisfaction from spending time with the children of his sister Laura, an anthropologist at Berkeley. He laughs with friends and pours his energy into lawsuits, news releases, and his constant stream of reports on wrongdoing and its cures.

If Nader’s work is his wife, reporters are his mistresses. Nader says that little of what he has accomplished could have happened without committed newspeople who spread his message — prominently and often. But most of the dozen or so reporters on whom Nader depended in the sixties and seventies have retired or moved on to other work. And the news organizations that once covered Nader like white on rice have given him little more than briefs in recent years.

“It’s worse than ever,” Nader says. “The Post and the [New York] Times don’t pay attention and therefore the networks don’t pick it up. And in Congress, where a little publicity used to work, most of them are totally helpless now. You’ve got to come at them with a national outcry.”

ORDINARILY, Nader speaks in a rapid-fire barrage of facts and opinions. But when he reflects on his hometown, Winsted, Connecticut, his pace lurches to an easy saunter. His voice softens. His furrowed brow relaxes as he recalls bike rides out to the woods, long hikes, baseball games, and conversation at the family restaurant.

“Flying kites, playing football, running. There was a canopy of trees. Fall was spectacular. People knew me when I was three.”

Nader reverts to crusader mode when he sees a developer mowing down trees and houses to build condominiums in Winsted. “He’s changing the very nature of the community he’s selling. He has no concern for the streams and lakes and trees and schools and roads. He’s your typical uni-dimensional booster, exploiting the natural environment and quality of life that he keeps talking about. His places will be slums in twenty years.”

“The development issue is the ball of wax,” Nader’s other sister, Claire, says. “It has to do with schools, the ecology, taxes, politics, access of citizens. Ralph has reached the limit of what he can do at the Congressional level. Coming back home, this project makes a whole of what Ralph, Shaf, and I have been trying to do. In a small community, you can see results.”

To help small towns recapture control of development, Nader proposes establishing a network of community advocates, lawyers working for the people. Each Nader advocate would be in touch with other towns’ advocates. “It would be a thing of beauty,” Nader says. “All of them connected by fax. Something happens on the Hill, and by 5 P.M., the advocates have kids out on the streets of hundreds of towns with fliers, shouting ‘Extra, Extra!’ This is not just recalling cars. It is restructuring the economy.”

Nader has created a model in his hometown by hiring an advocate, Ellen Thomas. In her first few months in Winsted, Thomas helped resurrect a taxpayers association that had been dormant for a decade and helped citizens tum back the town budget. She says that she is not opposed to all development, only to poor planning, but people she has worked with, people such as Taxpayers Association officer Walter Miller, say that Thomas has been crucial to their effort to curb development. (“I’m a heating and air-conditioning contractor, but if we never had another house in Winsted, I’d be happy,” Miller says.)

Nader asked townspeople about the concept of a community advocate, and they approved by a two-to-one margin. But asked if they would pool their money to pay for such a person, they said no by the same margin. Undaunted, Nader says that he is still working on how to pay for community lawyers; for now, the Nader family trust pays Thomas.

Nader says that the advocate will do what people want her to, but he already knows how he wants Winsted to look in ten years. “A very high level of civic involvement, where the schools teach in part by involving students in community problems, where money is spent wisely, taxes are equitable and minimized. The cable system will have more local programming. There’ll be more farmer and consumer markets, data banks on what other towns are doing, group-buying networks, places for young people so they don’t have to hang around. They’ll stop tearing down old buildings, have a model community college, good sidewalks, good roads, good trees, lots of preventive health care.” He went on for a solid minute.

It is a revolutionary vision of a future not unlike small-town America of the early twentieth century. Nader has always seemed to be pushing a fanciful future — air bags for cars, sports leagues in which the fans call the cards, indestructible household products. But the more he talks, the more he seems driven, especially recently, by a kind of Frank Capra nostalgia.

“When we were growing up, you could hear the cows mooing. I had the town’s biggest paper route; on foot, 129 papers. Small towns are not as much crime, not as much corruption, not as much evil.”

Like his utopian father, a Lebanese immigrant who had the gifts of argument and imagination, Ralph Nader is a simple, old-fashioned man. To this day, he insists on using a manual typewriter. He does not understand the attraction of computers. He may be the last person in the country who uses carbon paper.

“Ralph tries to set an example for how he thinks life should be lived,” says Claybrook, perhaps Nader’s closest friend. “He is a nineteenth-century disciplinarian. He may be idealistic, but he’s not stupid. He knows people will behave as they do, but he also knows people’s greed and consumption are fueled by an economic system that encourages them to do things that aren’t good for them. It’s a whole lot easier to control twenty-five car manufacturers than to control the driving habits of 155 million drivers. So Ralph tries to create a better marketplace, because that will help us change the way we live.”

Along these same lines, Nader recently persuaded his Princeton class to create, as its thirty-fifth-reunion gift to the university, a program of classes in citizenship for current students. Members of his class will teach students how to work for the public good in their respective fields.

Now the nation’s voice of honest progress is looking homeward, trying to recreate the small-town world of his youth through community advocates and lawsuits. Ralph Nader’s America is a paradise lost, a nation that has taken the simple, good ways of its past and poisoned them with greed and evil. This vision has been with Nader for half a century. He heard it argued to diners at his parents’ restaurant. He absorbed it on long walks through the Connecticut hills. He practiced it on his brother and sisters and even on classmates who would rather have talked about girls and ballgames. And then Nathra Nader’s son decided to take his father’s message from the lunch counter to the nation.

No responses yet