Reading Room: Danielle Allen ’93’s Fresh Reading of a Familiar Declaration

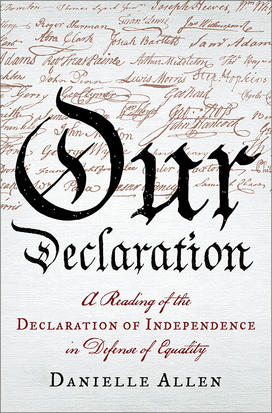

Though she is a political scientist with two Ph.D.s, Danielle Allen ’93 never had read the Declaration of Independence as a serious work of philosophy until she taught a night class at the University of Chicago in which many students were unemployed or stuck in dead-end jobs. Working her way through the 1,337 words of one of the foundational documents of our nation, she found herself fully appreciating its achievement, especially the phrase “all men are created equal.” Those classroom discussions inspired her to write Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality, which lays bare the structure of its argument and the deeper meaning of its language.

Her central argument is that, while Americans are quick to celebrate the declaration’s defense of individual freedoms, they tend to forget its emphasis on equality. They see government as a threat to those famous freedoms, rather than their guardian. “The paradox,” says Allen, who is a professor of social science at the Institute for Advanced Study, “is that in order to be free, we have to build this shared instrument [of government and laws] that we use to protect ourselves, and the only way you can build that is on the basis of equality.”

Allen puts the declaration’s most familiar words and phrases under a microscope. What does it mean to be “self-evident”? Not, she answers, that a claim is instantly recognizable as true, but that its truth becomes more apparent as we examine it. The word “endowed,” she notes, comes from doto, the Latin word for “provide with a dowry.” In a text that essentially is a decree of divorce from King George III, the legal language bolsters an unshakable claim, Allen says.

The book also launched a controversy — over punctuation. Allen maintains that the National Archives’ official transcription of the declaration has a period where it should have a comma, as most early versions do. The period appears after “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” removing the role of government from the list of self-evident truths. With a comma, government becomes not a threat to those rights, but their protector.

The declaration was transferred to parchment by Timothy Matlack, clerk to the secretary of Congress, who added a few flourishes of his own. Among those, Allen argues, is a mid-sentence capitalization of the word “We,” transforming a group of colonies scattered along the Eastern Seaboard into a single nation.

Nature’s God by Matthew Stewart ’85. “His thesis is that Spinoza is the big, unrecognized influence on the Founding Fathers, and that, with regard to religion, they were more radical than we realize.”

No responses yet