Reading Room: Jane Dailey *95 on Race, Sex, and Civil Rights

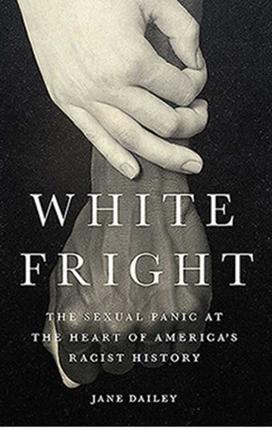

Jane Dailey *95, associate professor of American history at the University of Chicago, has long been a student of Reconstruction and 19th-century race relations. But her latest book, White Fright: The Sexual Panic at the Heart of America’s Racist History, concentrates on the 20th century, asserting that the fear of interracial sex and marriage was at the heart of Southern resistance to civil rights. It was “an extremely powerful political argument,” she says. “I was focusing on why this argument worked, and how hard it was for the civil rights movement to deal with it.”

How did you arrive at this topic?

My first book was about a successful interracial coalition in Virginia that ruled the state in the 1880s. It was brought down finally by a combination of violence and fraud and sexualized race politics that centered on public schools. I thought, “This sounds a lot like the way people reacted after Brown versus Board of Education.” So I leapt forward a century, and this book started there.

You talk about anxiety around fluid racial categories. Doesn’t that owe much to coerced sex between white men and enslaved Black women?

That’s what W.E.B. Du Bois and others always said. There is an anxiety, and that’s one reason that anti-miscegenation laws have so much power — as a bulwark against what white supremacists consider this horrible future of racial nothingness.

What about white men’s worries that white women might find Black men attractive?

Ida B. Wells basically got run out of the South for saying white women are not being raped — they are having consensual relationships with Black men. The myth of the raped white woman holds up the pillar of lynching and white supremacist violence and domination [of the time].

Loving v. Virginia was obviously a landmark in the trajectory of civil rights.

That case happens because Mildred and Richard Loving got married in Virginia, which was one of the states that still forbade interracial marriage. Somebody outed them. They were arrested in the middle of the night. And when they came before a judge, he gave them a choice: Exile or jail. They chose exile. They went to Washington, D.C., but they loved Virginia, so they kept slipping back to Virginia, where they were eventually caught again.

You say that while many white civil rights advocates were trying to distinguish between political and social equality, Black people rejected that rhetoric.

African Americans didn’t draw that line, and they resisted drawing that line all the way through Loving v. Virginia. That was one of the things that surprised me — how forthrightly African Americans demanded equal sex and marriage rights.

So white supremacists’ beliefs that political rights would lead inexorably to interracial marriage were correct?

They weren’t wrong. And white advocates for civil rights would say, “No, you’re crazy.” White supremacists read the desires and demands of African Americans in some ways more correctly than some of African Americans’ own civil rights allies did.

What about the role of church groups?

Church groups played complicated roles. I didn’t expect to find Christians duking it out over the interracial sex and marriage question. The sinfulness of race mixing became a potent argument after the Civil War.

What about the impact of World War II?

Advocates for civil rights grabbed onto anti-fascist language to bend it to their own purpose. Long before the war, African American writers and thinkers were already saying, “Any kind of racial discrimination is incompatible with democracy.” Black soldiers were still living a segregated life because they were in a segregated military. But the lives of African American soldiers serving in England and Italy and Hawaii were much less rigorously policed by proponents of white supremacy. These soldiers were talking about new freedoms, which they were determined to bring home with them. And then they come back to an orgy of violence in the South.

What can you say about “white fright” today?

It doesn’t seem to be a great preoccupation of either whites or Blacks. If you look at the polling, people are much more likely to either countenance or approve of interracial marriage than they were in 1967. Obergefell v. Hodges [the 2015 marriage-equality case] is built on the logic laid down by Loving. Justice Anthony Kennedy reached right back and took Chief Justice Earl Warren’s human-rights language.

Interview conducted and condensed by Julia M. Klein

No responses yet