When critic Richard Dorment ’68 discusses a work of art, he draws you right into the action.

His description of Johannes Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance is equally compelling: “As the late afternoon sunlight filters through a yellow curtain at the upper left, the silence is almost palpable. The woman holds her breath. Nothing moves. Time stands still.”

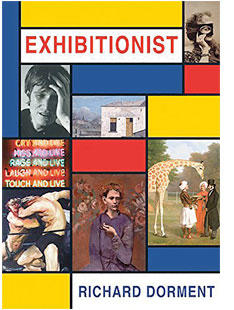

Chief art critic for the British newspaper The Telegraph for nearly 30 years, the American expat has compiled more than 100 of his weekly columns in a new book, Exhibitionist: Writing about Art in a Daily Newspaper. Dorment’s prose illuminates each entry alongside reproductions of the artwork.

Dorment might be considered an accidental art historian. Early on at Princeton, he sought to replace a classics course a few weeks into the semester — and art history, a subject he had not studied previously, was available. He was hooked immediately.

He later studied in New York, Rome, and London, earning a Ph.D. from Columbia while serving as assistant curator of European art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Following a decade as a freelance curator and exhibition designer in London, Dorment wrote weekly Telegraph reviews until his retirement last year. In addition to curating several major exhibits, he has written catalog essays, a biography of British sculptor Alfred Gilbert, and frequent pieces for The New York Review of Books. He was named Critic of the Year in the British Press Awards in 2000 and was made a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, a rank just below knighthood, by Queen Elizabeth II in 2014.

When Dorment began his journalistic career in 1986, London had no museum of modern art. “The very fact that you were writing about contemporary art was enough to inflame opinion when I first started,” Dorment says in an interview. “[Many] critics were shouting me down. ... I made no assumptions that my audience was with me,” and, initially, the critics included his own conservative newspaper. After a decade, though, as the climate changed — and the paper’s business consultants cited his column as a magnet for readers and advertisers — he was free to write as he wished.

Often, Dorment describes how familiar artists worked, putting the reader there with them. We learn, for example, that the early 19th-century French painter Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot composed his small The Island and Bridge of San Bartolomeo, Rome on site by drawing it first, then carefully filling the sketch in with subtle paint colors, “rather like a child with a colouring book.”

Though traditional art history was indispensable in his work — 18th- and 19th-century English art is his specialty — Dorment says “the art that you know about is not necessarily the art that you write well about. Very often the pieces that were the most fun to write were the ones where I was discovering the work myself as I wrote. That was one reason I loved doing contemporary art.” He expresses bafflement at some contemporary artists just as openly as exhilaration.

“Making up your mind about artists in one weekly review can be very dangerous, because sometimes artists, particularly nowadays, work in the long-term and you need a retrospective to see how it all fits together,” he says.

At times he describes seeing older paintings with new eyes, as when he decides that Georges Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières may not be as serene as he originally thought, or when he reports a sudden, fresh insight into the religious significance of the Vermeer.

In his final Telegraph article, Dorment leaves on this note: “The spirit in which I always wanted to write about all art [was] loud and clear and without hedging my bets. On my best days, that’s what I hope I did.” By Elizabeth Vogdes

On Vermeer’s Woman Holding A Balance

“Having looked at it for most of my adult life, only last week did I come fully to understand its meaning. I believe the woman in the picture realizes that the child she is carrying within her is like an empty balance, capable of turning towards good or evil, the flesh or the spirit. What is more, Woman Holding a Balance is a painting — one wants to say a parable — about the Catholic doctrine of free will.”

Dorment then notes that he realized Vermeer converted from Calvinism (in which the soul is predestined for good or evil) to Catholicism (in which the individual can choose between good and evil) upon his marriage in 1654.

Excerpted from Exhibitionist: Writing about Art in a Daily Newspaper by Richard Dorment ’68. © 2016 Wilmington Square Books. Reprinted with permission. Excerpts have been edited for length.

On Seurat’s Bathers At Asnières

“Three of the preparatory oil sketches reveal that in reality the boys sometimes swam naked … . But, just as [Seurat] edited the [dirty] work-horses out of the final composition, the artist chose … to give the two boys on the right of the picture bathing trunks.

“A clue as to why … is provided by the lovingly painted still-life in the exact centre of the picture. It consists of a white linen shirt, boots and a round straw hat with a delicate pink bow. To Seurat and his contemporaries, discarded clothes seen in conjunction with a nude figure by the bank of a river would have recalled the scandal created by Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe twenty years earlier. That picture was rejected ... on moral and aesthetic grounds, for it showed not a nude goddess in a sylvan glade but a contemporary woman, stark naked, having a picnic with two clothed men. …

“By comparison with Manet … Seurat’s Bathers feels not so much innocent as repressed. In cleansing the image of dirt — moral as well as material — Seurat created a picture which is cold and still, frozen at its core.”

No responses yet