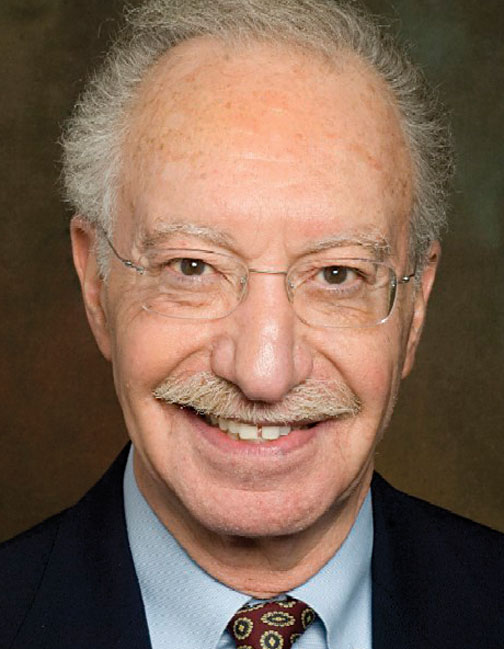

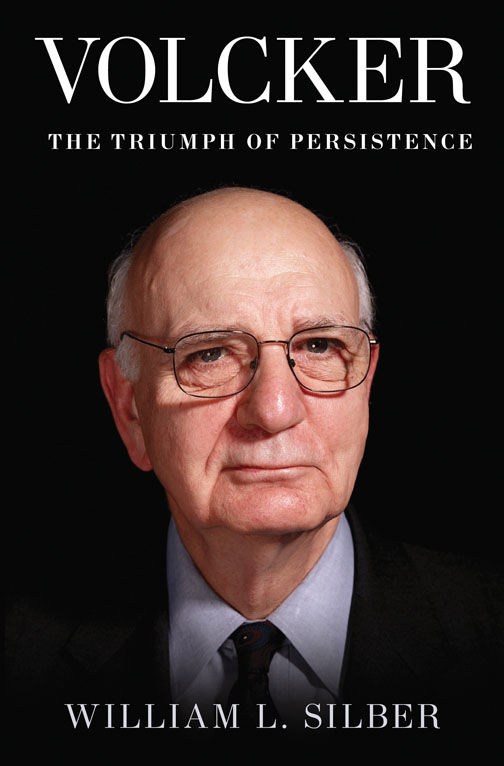

A few years ago, William Silber *66, a finance and economics professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, began a lecture to a class of M.B.A. students by asking how many of them had heard of Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan. All of them raised their hands. He then asked if they knew who had preceded Greenspan as Fed chairman, and all the hands went down. The name they couldn’t come up with was Paul Volcker ’49.

Silber thought their lack of knowledge was “a travesty,” he says.

Volcker, who has taught at Princeton off and on, was a senior Treasury Department official under President Richard Nixon, a post in which he shepherded the U.S. transition off the gold standard in 1971 — a delicate and controversial international challenge. Volcker then headed the Federal Reserve Bank of New York before being appointed Fed chairman by President Jimmy Carter in 1979 and reappointed by President Ronald Reagan in 1983. As chairman, Volcker successfully led the fight against double-digit inflation by tightening the money supply, which increased interest rates and initially led to a deep recession. The decision shaped the Fed’s hawkish approach to inflation for more than a generation.

With both the gold standard and the fight against inflation, Silber argues, Volcker helped restore the soundness and reputation of the American economic system.

Silber sought to make sure that future M.B.A. students — and Americans generally — didn’t forget about Volcker’s legacy by writing Volcker: The Triumph of Persistence (Bloomsbury Press).

Silber — who worked for Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisers and as a Wall Street trader, risk manager, and hedge-fund portfolio manager — said that one of Volcker’s most notable traits has been his resolute contrarianism. Volcker is a Democrat, Silber says, but one whose favorite book as an undergraduate was F.A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, a bible for libertarians. Part of the reason for his success in handling crises is that Volcker, an imposing man at 6 feet 7 inches and sometimes prickly, has been relatively unconcerned about political fallout.

Indeed, his iconoclastic approach didn’t always please politicians: Most of President Reagan’s advisers advised against Volcker’s reappointment, and President Barack Obama, despite giving it serious consideration, took a pass on naming him Treasury secretary. “I think they were afraid of him,” Silber says. “He couldn’t be counted on to spout the party line.”

Silber thinks Volcker’s “obsession” with inflation comes from a belief that inflation undermines trust in government. “We give the government the right to print money, and we expect that it will not abuse that right,” Silber says. Since Volcker “believes public service is the highest calling, anything that undermines it” — such as inflation — “is a sin to be avoided,” says Silber.

WHAT HE’S READING: Ken Follett’s new historical epic, Fall of Giants: Book One of the Century Trilogy

Why: Silber picked it because he loved Pillars of the Earth, Follett’s novel about the building of a cathedral in 12th-century England. “It had one of the strongest female lead characters I had ever encountered.”

1 Response

Robert N. Carpenter ’43

10 Years AgoVolcker '49's legacy

This is by way of supplementing “The legacy of Volcker ’49” (Alumni Scene, Jan. 16): Many people will say that the gold standard ended in 1933, when Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order preventing American citizens from exchanging their dollar bills for gold.

But the law requiring that the Federal Reserve hold gold backing against its currency remained on the books until 1968. And foreign central banks could get gold from the U.S. Treasury in exchange for dollars until Aug. 16, 1971.

The central concern with the euro is the budgetary deficits in European countries – not a relationship to gold or any other metal.