Remember (If You Can): To Age Out Is Not to Accept Defeat

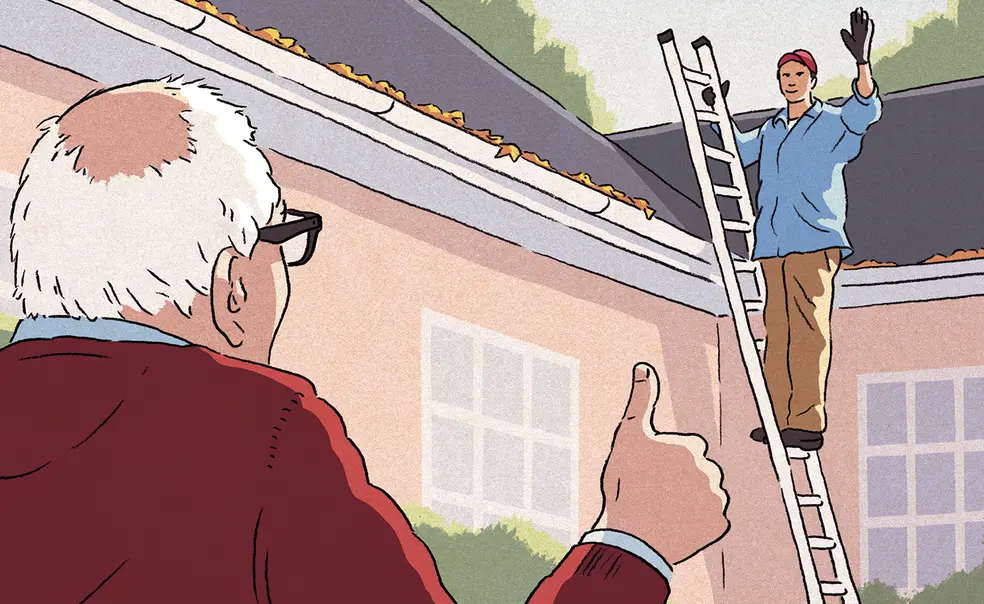

The other day I was on the roof cleaning out the gutters, a precarious and nasty job that makes a person reflect upon the inevitability of decay and degeneration. You are scooping by hand a lot of highly degraded organic matter — leaves, blossoms, insect carcasses, and mysterious layers of schmutz. When I clean the gutter on the back side of the house I am positioned at the edge of a sloping, metallic, and rather slippery roof, and there’s a chance I’ll go falling into space.

Simply climbing out the window onto the roof is a poignant challenge. Maturity is a stiffening process, and the ligaments that once gave you spidery flexibility become like rubber bands that someone mistakenly put in the freezer. You might even get wedged in the window, halfway in, halfway out. You might have to shout at passing dog walkers and ask them to call the fire department.

So as I cleaned the gutter, I asked myself: At what point do I “age out” of this effing chore?

The simple fact is that we age out of things, or should age out of them, if we are being realistic about who we are, what we’ve become, and what lies ahead.

This is not failure. This is just moving on.

It’s a lifelong phenomenon. A toddler ages out of diapers, a 5-year-old ages out of pajamas with feet, a 10-year-old ages out of lollipops at the bank, and a 13-year-old ages out of ordering off the kids’ menu. Growing up, moving on. At some point in adult life, you age out of couch-surfing when traveling. You just get a hotel room. You have arrived in life (at the Fairfield Country Courtyard Suites By Sheraton.)

And then you age out of sharing certain cultural and political opinions with the younger generation. Trust me, no one cares what you think about Taylor Swift or tattoos.

But it’s really in the fourth quarter of life that aging out becomes pronounced and potentially awkward. When youth slips away we may find ourselves clawing at it, desperate to get it back. There is incentive for denial because there’s a dark cloud on the horizon that gives us the willies. It signals the ultimate aging out. The D-word.

The hard decisions come when you need to stop doing things that you still want to do. You can still climb the ladder, but you shouldn’t. And people drop hints. Your doctor says things, your partner says things, and your boss stops making eye contact in the hallway (or did you imagine that?).

You find yourself trying to persuade yourself that you are not obsolete. “Still got it!” you tell the mirror, which replies, “Yeah, sure you do.”

This is all part of what we could call the hard audit. The hard audit looks clear-eyed at your strengths and weaknesses, your good and bad habits, your virtues and vices. It interrogates nagging worries and suspicions to see if maybe there’s something deeper going on.

This summer I learned a new word: anosognosia. It’s when a person has a disorder or disease but doesn’t recognize it.

The concept could be applied to non-pathological realms. When does your professional performance no longer meet your own high standards? We all struggle to discern how much gas we have left in the tank because there’s no reliable biological gauge for that. Something just tells you one day that you’re running on fumes.

The whole country went through this aging-out phenomenon this summer. It was painful to witness. Joe Biden felt like he still had what it took to lead our country for another term. He believed in himself. But too many others had a different opinion, believing he’d aged out of the most important part of a politician’s job during an election year: winning the election.

Biden came to Princeton my freshman year. I don’t think I’d ever seen a senator up close before, and I was impressed. He was charismatic, confident, and transparent in his desire to be president someday. Of course, that day finally came many attempts and more than four decades later.

I hope he’s not bitter about what happened with this year’s election. At some point you have to age out of regret, or at least park it where it can’t do any harm — like in the satellite lot.

It’s best not to rage against the dying of the light. But if it makes you feel better, you can send the dying of the light a terse and slightly pissy email.

Joel Achenbach ’82 covers science, health, and politics at The Washington Post, where he has been a staff writer since 1990.

8 Responses

Thomas Hunter Haddon ’88

1 Year AgoPerfect Blend of Humor and Perspective

Thank you, Joel, for this essay. Due to the medication I need to take for another year, I have never felt weaker. Due to winter coming on, there has never been more that needs to be done in the backyard. Your essay delivered the perfect blend of humor and perspective.

Norman Ravitch *62

1 Year AgoOn Hiring Out Dirty Jobs

Regardless of age, my philosophy has always been never to do something distasteful that you can hire someone else to do.

Kristin White ’82

1 Year AgoWitty and Poignant

JoelSpeak is so intrinsic it will never age out. Thank you for once again nailing something with wit, poignancy, and clean truth.

Francine Mathews ’85

1 Year AgoYou’ll Never Age Out of Writing

Joel, you’ve skewered the truth as ever. Happily for us, you’ll never age out of writing.

Maurice Heckscher

1 Year AgoAn Alternative Aging Mantra

I went to Penn many moons ago and we hated Princeton (cuz we couldn’t get in?). But I have to say you’ve written a beautiful essay. I agree with you whole heartedly but must add that, at least mentally, I endorse the Clint Eastwood mantra: “Don’t let the old man in.”

Wayne Coffey

1 Year AgoOn Aging Out

This is wonderful, Joel. I personally aged out of gutter-cleaning some years ago. Blame your former roommate Jordan Becker ’82 for directing me to read your work.

Susan Gemmell ’82

1 Year AgoStill Got It

Joel, you’ve still got it with regard to writing. This is beautiful.

Amanda W. Kingsley ’84

1 Year AgoBeautifully Written Essay

Oh how I love this. Beautifully written — and so many truths sprinkled throughout.