Renowned History Scholar and Princeton Professor Emerita, Nell Irvin Painter Explores Decades of Black Political Thought in New Book

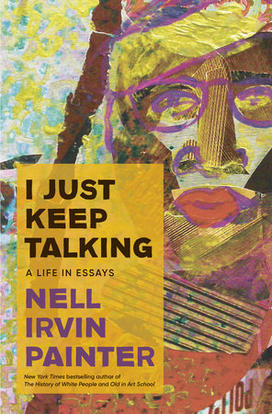

The book: From The New York Times bestselling author of The History of White People, comes a collection of essays with original artwork that explores decades of Black political thought, history, and the legacy of racism. Nell Irvin Painter draws on her expertise in these fields in I Just Keep Talking (Doubleday). This book is a testament to the complexity of American history, as Painter investigates topics from the history of exclusion through Toni Morrison’s work to the figures of Carrie Buck and Martin Delaney to the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election.

The author: Nell Irvin Painter, the Edwards Professor of American History, emerita, at Princeton University is a leading historian in the United States. She is the author of many books, including The History of White People, and was a National Book Critics Circle finalist for Old in Art School: A Memoir of Starting Over. She has been a fellow of the Academy of Arts and Sciences since 2007 and received honorary degrees from Yale, Wesleyan, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Dartmouth. She currently works and resides in East Orange, New Jersey.

Excerpt:

Introduction

Ego Histoire

It's a good thing I didn't die young. Meaning it's a good thing for my reputation that I didn't die during the full-blown era of White-male default segregation, discrimination, and disappearance that wound down only yesterday. I would have disappeared from memory, just another forgotten Black woman scholar, invisible to history and to histography. So much in me-a dark-skinned Black woman, always very smart, born in Houston in the Houston Hospital for Negroes in 1942-was suited for disregard. No family drama. My parents were married; they stayed married in as good a heterosexual marriage as Americans born in 1917 and 1919 could have and that lasted 72 years-until my mother's death. We were never poor, though never rich, and physical violence and addiction played no part in my family. My parents supported me emotionally and materially for more than 40 years. There's not much there in my life to match what my country likes to recognize as a Black narrative of hurt. I remember speaking about Old in Art School in Seattle to a wonderful, warm audience largely of women. A questioner asked me what I do for healing. "Nothing," I said. "I'm not broken." Not broken, but on occasion frustrated, indignant-self-righteously pissed off with cause, often exhausted, but mostly and permanently grateful for the people who have protected me, mentored me, supported me over so many decades. Without you, there would be no me.

My Blackness isn't broken. It faces a different way. Mine is a Black ness of solidarity, a community, a connectedness to other people who aren't known personally, of seeing myself as part of other people, other Black people. My Blackness also brings with it an understanding of how other people see oneself, a seeing that can be hurtful, but not one's own fault. What W. E. B. Du Bois called "twoness" is not merely an exhausting from-the-inside/from-the-outside identity, but also an ability to understand more than one way of seeing oneself in the world, an awareness that some non-Black Americans lack. The history of that seeingness brings with it strategies, its armor-usually communal-for fending off hurt. Those strategies of protection aren't always as robust as society's strategies of meanness, which are legal, financial, and personal. But ours are better than nothing, better than going into a cruel world naked and unarmored. I wish other Americans weren't so wedded to an individualist identity, that they could understand themselves more as connected to other people, locally and nationally, and less with having to do with guns and not caring how one's behavior endangers other people. I wish we had more solidarity, even if that makes me sound like a socialist.

My Blackness celebrates itself through art-music, dance, painting, talking, writing-what I term Black studies. Since the opening of the cultural realm in the twenty-first century, people of all sorts have been able to savor the art of Black artists, and I'm proud to say that early on in this century that is no longer new, I brought Black visual art to the fore in my narrative history Creating Black Americans: African-American History and Its Meanings, 1619 to the Present (2006). Black history is full of pain, but it's full of something more: creativity. Since my years in art school, I've been adding to that legacy through my own visual art, including what you see in this book.

At the same time, I think it's right to tally up the injuries of slavery, to the enslaved and to their descendants in psychic and material terms-to the nation in its politics and social norms. What lives in me, specializing in post-Civil War history as a historian, are the wrongs that came after slavery and that live with me as experiences in my historical research, the terrorism, the lasting imprint of the politics of White supremacy enforced through violence, experienced for me intellectually, but harrowing nonetheless.

I live with the insults of the era of segregation; the grudging, thrown-togetherness of my parents' college, even though its little library inspired me before I was born; the economic scrimping of my family in the early 1950s to purchase our first home at Sixty-First Street and Telegraph Avenue in Oakland, because the Federal Housing Administration did not extend its favorable mortgages to African Americans. The automatic discounting of one's worth.

As a historian and as a visual artist, I have prospered, thanks to hard work and essential allies all along the way. But I know, I have seen, how the habits of sexism and racism discouraged others, and how the injuries of class held other women back, even held them down. In my final analysis, my own personal sorrow for my country's ways with race traces back less to slavery than to what came after in the decades of cruelty, extending into my own life.

I want to tell you some crucial things about me that have influenced my life's choices and, thereby, my work-what I have written as I have just kept talking over the course of more than 50 years and the fact that nowadays my talk is visual as well as verbal. How and why I stress specificity-individual specificity, geographical and chronological specificity-rather than generalization; as I read the past, one person cannot simply be substituted for another merely on account of sex or race. Just because I cannot know one person doesn't allow me to put another in her place. Knowing what, say, Harriet Tubman said or did doesn't let me assume the same for, say, Sojourner Truth. That said, I want to tell you when and where it was and with whom I was when my shaping, my molding, took place.

My family's roots reach back into Ascension, Baton Rouge, and St. Landry Parishes, Louisiana; low country South Carolina around Charleston; and Harris County, Texas. A century ago, their names McGruder, Donato, Lee, Irvin, Ashley-might have meant something, might have conveyed relative standing (McGruder, Donato, Lee) or not (Irvin, Ashley I don't know about). So far as I know, all but two of my ancestors were of African descent. My father's parents were Edward Irvin, an exquisitely skilled locomotive machinist, and Sarah Lee, a housekeeper. She, a very dark-skinned Geechee originally from a low country of South Carolina farming family who sought opportu nity in Harris County, Texas. My grandfather, a half-White bastard, a Texan born and bred. I met my Irvin grandparents only once, on a trip back to Spring with my father when I was a girl. I returned to Spring twice later, after their deaths, once during my dissertation research trip in 1971 and again during my book tour in 2018. In 1971 Spring was still very rural, still famed for the excellence of its white lightnin' whisky, whose excellence I can attest to.

In 2018 Spring still had fields and cattle whose days were numbered as Houston's suburbs encroached. The little house where my father grew up was still there in 2018, still with a horse in the yard, right beside the railroad tracks, but on the wrong side, the side away from the little (White) town center that now strives to market itself as a railroad tourist destination. My grandfather was a skilled machinist but was always classified as a machinist's helper, even as he had to train the White man who became his boss. My grandfather's half Whiteness wasn't enough to get him paid as a machinist, and my grandfather is the main reason I could never share the distinguished historian David Montgomery's fondness for American machinists.

My mother's father, Charles Hosewell McGruder, originally from

Ascension Parish, was a professor at Straight University in New Orleans (now within Dillard University) who married Nellie Eugenie Donato, a pretty, light-skinned-enough-to-pass student from St. Landry Parish, in 1902. She was a descendant of Donato Bello from Naples, Italy. By the 1930s Charles McGruder was one of Houston's leading Colored men; he died before my parents' marriage of "aggravated indigestion," caused, I reckon, by tiptoeing between Black and White Houstons in the 1920s and 1930s. In the late 1940s Nellie McGruder-"Maman"-came to live with us for a while. I remember her as a mean, paper-colored old woman who thought me ugly and trouble-bound because I was dark-skinned. My mother wrote about her difficult relationship with her mother in a memoir, I Hope I Look That Good When I'm That Old (2002). Maman spent her days with us crocheting funny-looking multicolored doilies, which we threw away as soon as she left. Did I, a knitter, inherit her needlework vocation?

My parents, Frank and Dona, fell in love at first sight in the library of the then Houston College for Negroes (now Texas Southern University), so I come by my bookishness from my very beginnings. They married and moved to Oakland, California, in 1942. For their migration, I remain eternally grateful. I never was meant to be a Southerner. Frank and Dona didn't escape right away; I was born in the Houston Hospital for Negroes, an institution that Texas had named specifically to let everyone know it was meant to be lesser, as in separate not intended to be equal, one of many Southern institutions created after the Second World War against Nazi Germany had given outright, unmitigated racism unsavory connotations. My parents knew these hastily created institutions, having met in one of them, as the NAACP Legal Defense Fund was harrying the South over the lying, mean spirited state of its public education. Texas jerry-built my parents' college, the Houston College for Negroes, under another discounting name.

Frank and Dona escaped to the San Francisco Bay Area. They stayed married. I stayed bookish.

I was their only surviving child. Tragedy made that so, for my older brother, Frank Jr., died during a routine tonsillectomy, a procedure then that was the right thing to do for one's children.

My brother didn't survive his surgery, but how do your parents survive the loss of their son, picking up his body in death, not in life? How could they get to the next day? How could they carry on from this "unbearable grief," as my colleague at Princeton Elaine Pagels termed it after just such a loss?

Frank and Dona gave me the same reply every time I asked: ''We had you," they said to me. They poured all the love they had for one lost child into me, Nell, endowing me with love for two children, two children's bounty of love, two children's expectations. From my earliest childhood, I flourished in the love for two children, not just one. In the mid-twentieth-century America I grew up in, I needed it all.

How did all this play out for me as a young woman around 1960?

Excerpted from I Just Keep Talking by Nell Irvin Painter with permission of the author. Published by Doubleday. Copyright © Nell Irvin Painter, 2024.

Reviews:

“Nell Irvin Painter is one of the towering Black intellects of the last half century…[I Just Keep Talking] is more than an odyssey for the senses; it’s a revelation that will inspire courage in anyone seeking to express their truth.” — Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor, Harvard University

“Nell Painter is one of the most important and versatile American historians of the last half century. This stunning array of essays…contains a potent autobiographical sizzle from introduction to the end…Prolific, provocative, and with a voice all her own, Painter reveals with admirable vulnerability a mind in transit through time.” — David W. Blight, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

0 Responses