We came to Princeton on a stifling Tuesday in June, in a racketing, ill-tempered rental car picked up in Philadelphia. It was three o’clock in the afternoon when we drove in through the post card-pretty truck farms and fields that surround the town, in past Palmer Stadium (“Oh, Heyward, even the stadium has ivy on it!”) and the old brick and stone houses that once housed who knows what affluent tradesmen and faculty members, and now house near-identical swarms of barefoot, Levied students, some of whom are women.

They were sitting on stone walls and verandas, stripped as far as decency allowed against the smothering New Jersey heat, watching the rental cars and station wagons full of wilted alumni and families stream in for Reunions weekend. It was my husband’s 25th-Class of ’48, the Big One, as the pennants and orange beer cans, courtesy Budweiser, under the great tent in the quadrangle that served ’48 as its headquarters, proclaimed. He hadn’t been back since the middle ’50s, and those tall, grave young colts with long sheens of smooth hair were the first women undergraduates he had ever seen on the Princeton campus.

“Goddammit, it just doesn’t look right,” he growled, and I giggled. I had come to Princeton primarily to giggle. Indeed, I had been giggling ever since the previous November, when a letter arrived for me which began, “Dear’ 48 Wife: Well, the Big One is coming up. And here’s a chance to really please your old man this Christmas. For only $49.95, you can order his class blazer in time for. . ,”

A product of the rural South and graduate of a large Southern university whose lackadaisical alumni can hardly be persuaded to attend anything but boozy, murderous football weekends where they wear orange felt beanies and howl obscenities at Bear Bryant, I simply knew nothing about the graceful ritual of the Ivy League reunion. In fact, the very thought of middle-aged men in beer jackets, wailing “Goin’ Back to Nassau Hall” on the gray stone steps of that august edifice and pounding each other on the back while examining each other covertly for signs of encroaching senility, struck me as one of the funniest things I’d ever envisioned. And when the schedule of events for Reunions duly arrived, I read it and did a great deal of grousing. “You get to do all kinds of neat things like going to stag smokers and class dinners and being in the P-rade – whatever the hell that is,” I whined. “And I get to tour the president’s rose garden with a bunch of wives who all went to Smith or somewhere and doubtless belong to the Merry Giggle Hunt and play tennis together and will have on some little Valentino nothing, and think I’m a hick.”

In regrettable point of fact, I have always been a bit in awe of Heyward’s glossily ivied classmates and their tasteful backgrounds, and have envied those who walked easily in the cloistered world of Princeton and its peers ever since I read Scott Fitzgerald (who apparently never stopped carrying a big stick while he walked there softly, either). I have the traditional insular, truculent Southerner’s distrust of the East, and would dearly love to be able to toss off references to tea at Dean Conant’s or the Yale-Princeton weekend when we went back to Colonial and ran into old Thornby, who’s just back the Middle East and tells marvelous stories about the Saudis.

But I can’t, and no husbandly attempts to assure me I would Fit Right In and Everybody would Love Me assuaged the niggling certainty that the men would tease me kindly like a retarded child and the women would tell me what a sweet dress I had on, and everybody would agree behind our backs that old Siddons certainly had himself a quaint little second wife.

So I took refuge in ridicule, and managed to make quite an ass of myself to our friends in Atlanta before we left.

On that Tuesday afternoon, though, I was a little subdued. We had made a short detour earlier in order to drive through the campus of the Lawrenceville School, and I had fallen under the spell of those great, dreaming old brick buildings and mammoth elms and green playing fields where Dink Stover and the Tennessee Shad had earned themselves immortality and a place in my heart long ago, when I read Owen Johnson’s wonderful Lawrenceville Stories. They had seemed as remote and underwater to me then as The Wind in the Willows and The Secret Garden, pure, gentle fantasy. But there was the Jigger Shop, and there the football field where Dink underwent his first rite of passage, and there the infamous dormitory roof. Something began to curl into my head like old, old smoke.

We nosed into a parking space and got out, pulling sticky clothes away from our backs. “It’s early yet to go out to Kiki’s,” said Heyward. “Let’s cut through the main gate and I’ll buy you a drink at the Nassau Tavern.” We walked in the hot, timeless afternoon, under vaulting old elms and cedars, past gray stone buildings with Gothic arches and leaded windows. There was an odd quiet, as old and deep as an ocean.

Through it we could hear a muffled splashing, and between two clumps of ancient cedars we had a long vista down to a small, heat-mirrored lake. A long, graceful shell was fleeing over its surface, with a lean, synchronized crew pulling effortless oars. The lead man had a megaphone. ‘‘Are they. . . ?”

“Sculling,” said Heyward, looking sidewise at the silly little smile curving my mouth.

A bell with a voice like eternity spoke four times, lost somewhere up in the canopy of green, its notes hanging long and bronze and perfect in the ringing air. A young professor with a fine beard was gesturing to a handful of students slouching on the grass under an enormous elm across the campus. “It’s all a stage set,” I said, but I said it sleepily, sliding into the day and the place. The Princetonization of Annie had begun.

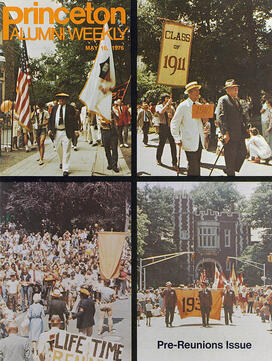

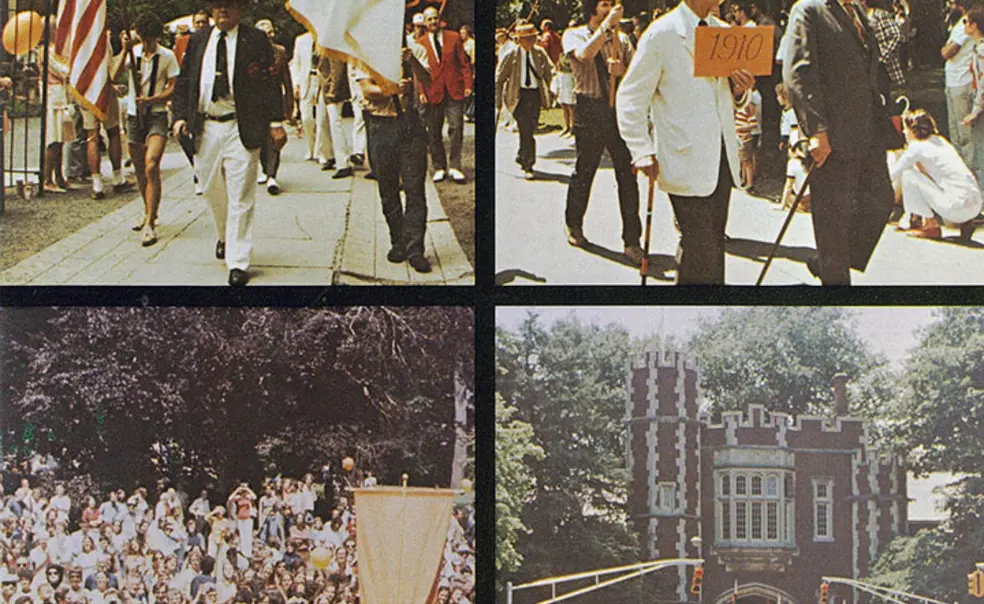

Princeton’s reunions, I learned during their course, are probably the most ceremonial and time-hallowed in the Ivy League. All the classes that have living members attend, from ’01 up to the newly graduated class. Each has its own headquarters, usually under a canopy in one of the school’s countless gray-bastioned quadrangles, and these enclaves are as distinct in ethos and as jealously guarded as an Englishman’s club in the savage tropics. Each class has its own uniform, and they range from a perfunctory orange fedora and black-patterned tiger tie (Class of ’25, I think) to the full and correct regalia of the Class of ’48: Gray slacks, white shirt, orange-and-white striped seersucker blazer, tiger-patterned tie, white bucks, and white straw boater with orange band. Some later classes, with only a few attending, were sensible in Bermuda shorts and tee shirts. Some space-age alumni sweltered in silver nylon space suits. One class puddled around in swathing Batman capes. There were maybe 1,500 alumni on campus, all dressed in whatever their class had espoused for the weekend, and the result was absurdly like Disney World, moved lock, stock, and barrel into the Cathedral of Notre Dame. Perhaps even more absurdly, it didn’t look absurd. Princeton reunions, like The Turn of the Screw, have the ability to suspend one’s belief in an orderly, rational universe.

The 25th reunion, no matter what the individual class, is always the “big one” and the best attended, and when we drifted up to the gate of Heyward’s, where a genial, sweating guard admitted us, the scene beyond looked like a marriage of a garden party to a scene from The Greatest Show on Earth. A canopy covered the entire quadrangle, which had been deeply sawdusted. Long, wooden trestle tables were full of orange men and summer-frocked women drinking complimentary Budweiser served up from a long bar by amiable, only slightly supercilious undergraduates. At another long table, pretty coeds dispensed reunion kits, tee shirts, boaters, pennants, and the indispensable badges shouting Class of ’48 and your name, without which you hadn’t a prayer of getting into any of ’48’s activities. A rock band was booming, throngs of children were shrieking underfoot, clumps of balloons bloomed in corners, assorted campus dogs lolled in the cool, damp splotches where the beer coolers leaked. Virtually all the men, being identically clad, looked like my husband, everybody seemed to know everybody but us, it was precisely 100 degrees under the Big Top, and I had a desperate urge to run and take refuge in a dark, air-conditioned movie theater. Or even better, a bar. Taking a deep breath, we dove into Reunions.

It was a weekend to be remembered as you might remember a dreamlike snorkel under the waters of the Great Barrier Reef. The regular, slow turning of each sun-stricken day was punctuated by ritual: Breakfast in the cool, dim Commons or the air-conditioned haven of the Nassau Tavern. Tennis or a father-son softball game down on the burning field. The eleven o’clock beer, tepid before you finished it, under the tent, where Heyward’s classmates proved to be genuinely nice and did remember him fondly and did not patronize me, although some few were indeed in the diplomatic corps or the Cabinet, and one was Bowie Kuhn, the commissioner of baseball. I learned to my reassurance that even Cabinet members go gray or balding; that even captains of industry have shy second wives, that even Bowie Kuhn sweats under a stifling canopy and removes his limp jacket. I learned that even heiresses get limp-haired and grass-stained at 100 degrees, and chase children just as peevishly as my own friends and, moreover, did not patronize me, being unsure that a sweating, grass-stained, anonymous southern wife was not one of them. Sweat is a great leveler.

Lunch, if you hadn’t fled again to the Nassau Tavern, was fried chicken and hot dogs and potato salad and beer, and there were regularly scheduled afternoon tours of the Art Museum, or erudite lectures on “Agribusiness in the Electronics Age” and “The Future of the Humanities in the Coming Technocracy,” but I think everybody went back to his hotel or motel room and slept. We crept back, each afternoon, to the lovely 200-and- some-year-old farmhouse out in nearby Hopewell, where an exceedingly forbearing friend of my husband’s family gave us his open-hearted hospitality, and fell into heat-and-beer-stunned sleep, cool at last within two-foot-thick stone walls.

All over the campus and out in the beautiful old town, in the evenings, there were cocktail parties, where refreshed alumni and wives gathered for cool drinks and civilized talk. Ostensibly. At the first one, scrubbed and resplendent in long, crisp white pique, and hollow from a day of sweating and no food, I got gently and sweetly drunk on two gin and tonics, lost my identification badge and earrings, called a something-or-other of Protocol in Washington a pussycat, jitterbugged baroquely with the publisher of some impeccable little literary quarterly, and fell asleep propped against the host’s Silver Cloud, talking to an elegant lady about Moliere – a gentleman about whom I know nothing at all. I was wakened and taken home in disgrace by my properly mortified husband, and cringed redly into the wee hours at the thought of encountering the Protocol Man, the Publisher, or the Elegant Lady the next day. As it turned out, none of them remembered any of it. It was that kind of week.

But it was another kind of weekend, too, one that touched a deep chord within me, a well of poignance and simple love of continuity and tradition that, having no special academic traditions of my own to draw from, I never knew I had. Already bemused by the long heat, the very tangible old spell of the university, and the strong undercurrent of nostalgia, I understood on Saturday at least a part of what draws these men, brisk, productive, good grown men, back like children to a picnic every year.

It was the Saturday of the P-rade, the one event which had amused me most of all on the activities list. “Dear heaven, Heyward, 1,500 grown men all dressed up and marching? From where to where? It sounds like the Elks.” And my husband had grinned uncertainly, because he’d never been to a P-rade either. For that uncertain grin, for that diminishment of pleasure, however slight, I have ached and repented ever since.

On the morning of the P-rade, under the tent, something slightly scalp-crawling was building up. We wives clung closer together, in tight knots, feeling our men draw away from us at last and into the body of ’48, into a whole where we couldn’t follow, as if into the ranks of Eleusinian initiates. Into Princeton. The Class Picture was taken on the steps of Blair Arch, and we saw them all together for the first time, a tiered shoal of orange and black and pride. The rock band, which had for days been whumping out Bacharach and Jim Croce, crashed into “Goin’ Back to Nassau Hall,” and I heard it for the first time, this song I had giggled so gleefully at, rolling at me across Princeton University as it had, on this same day, for reunions out of mind. I couldn’t find my husband in the throng and wouldn’t have known him if I had; they were all gone away from us now. I couldn’t see through the lens of my borrowed Nikon for the tears, but there were 250 other ’48 wives who were fogging up their lenses, too, so it didn’t matter.

After the picture was taken, women in quiet groups moved away across campus to find seats along the P-rade route. It ran about a mile and a half, from Nassau Hall and the main gate down to the athletic field. The elm-shaded streets were literally jammed: with the wives and families of 1,500 alumni, with faculty and students, with townspeople ranging from elderly, erect old men to young mothers in Bermuda shorts and groggy babies in strollers. Along with a sturdy, brisk girl who had been to several reunions and, therefore, knew the ropes and the best viewing spots, I found a niche on the curb in front of my husband’s club. For what seemed a very long time, while the classes massed in their prescribed ranks back at the main gate, we waited. It was a pleasant crowd, but a quiet one.

And then you heard it, very faint, very far away, the percussion first. “Goin’ back. . . goin’ back. . . goin’ back to Nassau Hall . . .” and then a regular cadence, which turned out to the feet of marching men, and then 1,500 male voices, aged 21 to 91: “. . . goin’ back.. . goin’ back.”

And then the band turned the corner, the sound rolled down the old street like a tidal wave, and, “Oh, God,” I sobbed to brisk, no-nonsense little Ginny, who’d been through this so many times and was surely going to laugh at me, “I’m going to make the most awful damned fool of myself.” But her face was buried in her hands and her shoulders were shaking, and she didn’t hear me.

They were absolutely beautiful, these Princeton men marching by on a sunny June Saturday, and I don’t give a holy hoot in hell that I cried for the one hour and 15 minutes it took them to pass me. The band, then the tall, new young president, smiling; then, in the place of honor directly behind him, the Class of ’48. Row after orange row of them, singing their song, on their day on their street on their campus. I couldn’t spot Heyward, but I’m glad; he told me later they’d all been trying hard not to weep openly, and nobody would look at his wife.

Behind them came perhaps the most poignant and gallant of them all, the Old Guard. The very oldest living Princetonians, singing “Goin’ back. . . ” for what surely must be, for some of them, the last time. We had seen them during the week, in the Tavern or ambling about campus, natty in their bright uniforms, but so frail, so tentative, some leaning on menservants, some with gentle, bewildered old wives on their arms. Some of them will never make that march, I’d thought, not in this heat. And indeed, some were waving jauntily to the crowd from an open limousine. But others, by God, walked every step of the way, swinging along erect and vibrant, with perhaps only the common cord of Princeton sustaining them. And one, Class of ’15, rode a unicycle. Roars of pure love swelled to meet them; be there were many children and grandchildren and even great-grandchildren in the crowd, and more than one had a son and grandson marching with them, in other classes. But had there been no kindred soul there for any of them, they would have affected us the same. As they turned the corner onto Prospect Street, the crowd rose spontaneously to its feet, sun hats off, and all along the street they rose till the entire street was lined with standing people as the Old Guard went marching by.

And so it went, class after class, getting younger and brisker of step, until the seniors ended it up, the largest of all, starred with young girls’ faces, singing “Goin’ back . . . goin’ back.”

Trudging back to headquarters, steaming hot and sunburned and emptied of emotion, I got lost and had ample time, wandering through the maze of shady quadrangles, to ponder why this simple, almost simplistic ritual, this near-archaic tribal rite, had moved me so deeply. I came to no conclusions. It seemed to me then, lost on that campus itself lost to time, that it was simply a right and good thing to honor something you loved very much as loudly and wholeheartedly as you could, and the devil take sophistication, civilization, undue examination, or whatever else threatened to get between you and it.

“Have you been crying?” said Heyward, when I finally found him under the canopy.

“Shut up,” I said, “and get me a beer.”

Adapted from an essay in the book John Chancellor Makes Me Cry, by Anne Rivers Siddons (Doubleday, 1975).

No responses yet