Wendy Laura Belcher, an assistant professor of comparative literature and African-American studies, has enriched the record of African literature with an exciting new discovery: a biography of a female Ethiopian saint written in 1672. Even some longtime experts on the literature of the continent were surprised by this finding — previously known to very few — and the length of the document, some 200 pages when printed in English.

Belcher lived in Ethiopia from ages 4 to 7 and never forgot the sense of wonder she felt at seeing an elderly Christian scribe inking a manuscript in a monastery, keeping alive a venerable tradition. Her discovery of the St. Walatta Petros biography came about in a surprising way: Researching a book about English man-of-letters Samuel Johnson, she was struck by his reference to Ethiopian women who defied Portuguese Jesuits in their attempt to eradicate Orthodox Christianity and replace it with Catholicism. Who were these fiery women? Belcher wondered. She went to Ethiopia to find out.

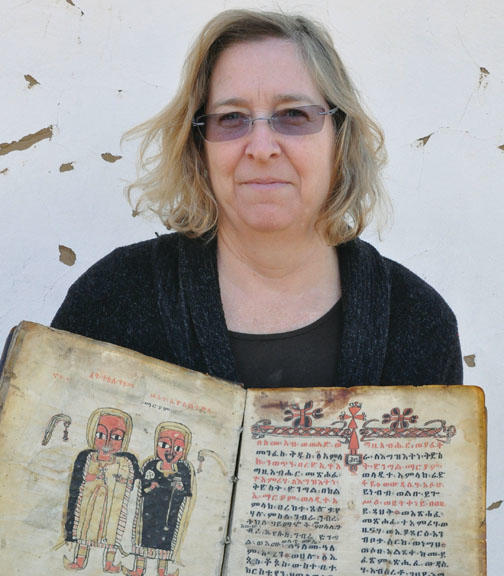

In a remote monastery on the shores of Lake Tana, Belcher was shown the biography of St. Walatta Petros, in three handwritten parchment versions — they are among the 12 copies of the original 1672 biography (now lost) that she has now uncovered. Each copy is written in the same ancient local language, with slight variations from one another. They tell the story of a member of the royal family who, outraged by the Jesuit incursion, left her husband and took to the countryside, rallying the people. Eventually she was successful in her campaign, and the Jesuits were slaughtered or fled in 1632. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church thrives to this day, preserving some of the quasi-Jewish dietary restrictions that the Jesuits abhorred.

Her intrepid discoveries make Belcher the counterpart of Renaissance scholars dusting off priceless manuscripts from ancient Greece and Rome on the shelves of monastic libraries, but with a decidedly modern touch: At Lake Tana, Belcher gently placed the manuscripts on the ground outdoors to photograph them with her digital camera.

Now back in the United States and working on a scholarly book, she is comparing all the extant manuscript variants, mostly written between 1710 and sometime in the 19th century, trying to understand the story of St. Walatta Petros more fully. “It’s quite thrilling to find a new manuscript,” Belcher says, especially one about an African woman, by an African author, in an African language, written so long ago.

0 Responses