‘Born to Do Something’

Attorney Brittany Sanders Robb ’13 may have made a name for herself working on behalf of Kobe Bryant’s widow, but she has been helping people since she was a kid

JUST OVER FOUR YEARS AGO, Brittany Sanders Robb ’13 made a momentous career decision, opting to leave her job as an associate at a prestigious New York law firm to return to her hometown of Kansas City. She and her husband, Andrew Robb, who was basically making the same move, were joining Andrew’s parents at Robb & Robb, a boutique personal-injury firm that the founding partners, Gary and Anita Robb, had built into one of the preeminent plaintiff’s shops in the country, particularly in the field of helicopter-crash law.

Sanders Robb had not even been with her new firm for a week when a call came in regarding a potential new case. It was from a woman on the West Coast whose husband and daughter were among the nine fatalities in a horrific helicopter crash on a fog-shrouded Sunday morning in the hills northwest of Los Angeles. She was looking for someone to represent her in a wrongful-death lawsuit, one that Sanders Robb knew would be the most high-profile helicopter-crash case in American history. This was how Sanders Robb came to work on behalf of Vanessa Bryant, the widow of NBA icon Kobe Bryant and the mother of the late 13-year-old Gianna.

Within six months, Robb & Robb worked out a confidential settlement with the defendants, Island Express Helicopters and the estate of Ara Zobayan, the pilot of the helicopter, who also died in the crash. The experience reaffirmed Sanders Robb’s conviction that she had made the right decision to leave the white-shoe world of defending huge corporations.

“Vanessa is a remarkably strong, determined woman,” Sanders Robb says. “Her [two surviving] daughters are so lucky to have her. I knew I wasn’t going to find the same fulfillment doing defense work. I wanted to help people, not companies.”

Sanders Robb’s pace of work has rarely relented in the four years since Bryant placed that call. The four Robbs are the only attorneys in the firm, and all of them work on every case, one of which was another highly publicized wrongful-death lawsuit that was expected to go to trial in February of this year.

The Robbs had been on it since 2018. The case was Udall vs. Papillon Airways, Airbus, filed in downtown Las Vegas. In the first week of January, it brought them to a courtroom on the 16th floor of the Clark County Justice Center, a striking glass and sandstone building with a grove of palm trees out front. Robb & Robb’s clients were Philip and Marlene Udall, a British couple whose 31-year-old son, Jonathan, and his newlywed bride, Ellie, were among five people killed in the February 2018 crash of an Airbus EC130 B4 helicopter on the west rim of the Grand Canyon. Jon and Ellie were celebrating their honeymoon, taking a sunset tour with three friends, also from Great Britain. Papillon, which has been specializing in helicopter tours since 1965, calls itself “the world’s oldest and largest sightseeing company.” It is based near Harry Reid International Airport, about seven miles south of the courtroom where Sanders Robb, 33, was handling the case as lead associate. For years, defense attorneys for Airbus had filed motion after motion in an effort to get the suit dismissed, arguing, among other things, that because it was a French company it could not be sued in the U.S. Sanders Robb signed a brief rebutting one of these arguments — which the defense attempted, and failed, to take to the Supreme Court.

Sanders Robb built her case on the failure of the manufacturer and the operator to equip the helicopter with a crash-resistant fuel system (CRFS), technology that has been around for almost 50 years and can significantly mitigate the risk and lethality of post-crash fires. CRFS tanks have a flexible rubber bladder encased in an aluminum shell and are equipped with breakaway rods and hardware that safeguard the tank from being punctured. Though Federal Aviation Association (FAA) regulations at the time did not require Papillon to equip this aircraft with a CRFS, the plaintiffs argued that negligence by both the manufacturer and the operator resulted in Jon Udall’s death. He had no injuries from the impact of the crash and was actually able to exit the aircraft before it was engulfed in flames when the old-school gas tank — Gary Robb likened it to “a milk jug” — burst, spilling fuel everywhere and resulting in burns on more than 90% of Udall’s body. Sanders Robb also blamed Papillon for not having emergency protocols in place; Udall was on the desert floor for seven hours before he was rescued and taken to a hospital, where he survived 12 more days before succumbing to complications from his burns.

“His suffering was unimaginable,” Sanders Robb says.

On the morning of Jan. 5, the second day of pretrial motions, Gary Robb’s cell phone buzzed with an email. It was from the attorneys sitting 10 feet away, at the defense table. After six years of motions, depositions, and an array of legal maneuvers to escape culpability, they were making an offer to settle. The hearing was adjourned. By the end of the day, an agreement awarding the Udalls $100 million was in place, $24.6 million from Papillon and $75.4 million from Airbus Helicopters. It is the largest public settlement in a wrongful-death case involving an individual in U.S. history, according to VerdictSearch, a data-tracking component of Law.com. Defense attorneys sought repeatedly to keep the amount confidential, but Sanders Robb said that Udall’s parents were unyielding in their insistence that the amount be made public.

“I think that once [Airbus and Papillon] really came to grips with our clients’ resolve and strength, they came to the table with [their offer],” Sanders Robb says. “No amount of money is going to give true justice to a family that has lost a son and a brother. This case was never about the money for Philip and Marlene Udall. Their goal has been to create change in the industry so other families do not have to suffer as they have suffered and as their son suffered.”

SANDERS ROBB BEGAN LIFE IN Elkton, Illinois, a small town outside St. Louis. That she found a path to Princeton and Washington University School of Law is a story in itself. Raised by a single mother, she was the first person in her family to attend college. After escaping an abusive, alcoholic marriage, Mary Sanders, Brittany’s mother, moved with her four kids to Kansas City, with the massive assistance of a divorce attorney who worked pro bono.

“She was just an angel,” Sanders Robb says. “She helped keep my mom and me and my sisters safe.”

Mary Sanders supported the family by working at a grocery store and cleaning houses and a church. For long stretches the family lived below the poverty line, getting by with public assistance and regular visits to a food pantry. In the months before Sanders Robb turned 6 years old, life got harder still. Her parents’ divorce was finalized, and her best friend, a girl named Kristin Bean, died after a long treatment for cancer. Sanders Robb and her mother were at Kristin’s house the day she died. Sanders Robb ran up to Kristin’s room. Seeing her friend’s toys and stuffed animals had a powerful impact on her, no matter her young age.

“Kristin taught me a valuable lesson even in her death that material things don’t matter ... and that no matter what you are going through, there is somebody who is going through a worse situation than you are.”

Brittany Sanders Robb ’13

“You don’t take the toys with you when you die. That was the thought that just clicked,” Sanders Robb says. “Kristin taught me a valuable lesson even in her death that material things don’t matter ... and that no matter what you are going through, there is somebody who is going through a worse situation than you are.”

When Sanders Robb’s sixth birthday came around, she told her mother that she wanted to donate her gifts to the hospital where Kristin was treated. It was the start of Kristin’s Kids Club, a philanthropy that continues to this day. Apart from gifts for sick kids, Sanders Robb’s club raised money with school-supply drives and made contributions earmarked for cancer research. She sent out flyers and recruited friends to help her fundraise and support other worthy causes. She designed and sold T-shirts to support her local VFW post, and shortly after 9/11, she and her friends raised $2,500 for America’s Fund for Afghan Children. When President George W. Bush visited Kansas City, 10-year-old Sanders Robb presented him with a check. The president handed Sanders Robb a presidential seal pin.

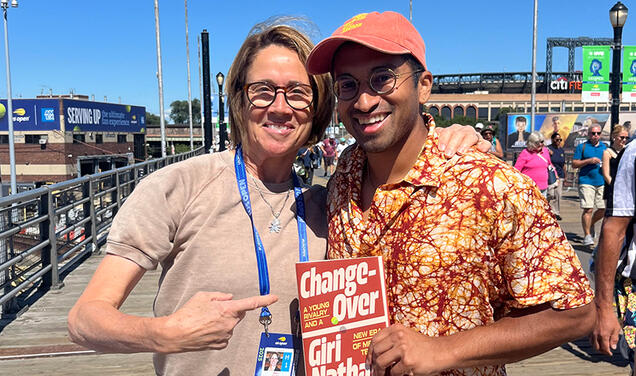

Kristin’s Kids Club’s longest running program is the promotion of an independent, supported-living community called Life Unlimited, the largest service provider for disabled adults in the Kansas City metro area. Every Christmas, the club throws a holiday gala at Life Unlimited with food, gifts, and carols. The party hosts include not just Sanders Robb and Mary Sanders, but an assortment of their nieces, nephews, and grandchildren. Nathan Powell, 33, one of the residents of Life Unlimited, has known Sanders Robb for 15 years. Last Christmas, his gifts from Kristin’s Kids Club included earbuds and a Kansas City Chiefs jersey. Powell has been a paraplegic since he was 12. He was mowing the lawn one day when a friend, playing with a gun, accidentally shot him in the chin and spinal cord. At 14, living in a nursing home, Powell was deeply depressed and “angry at the world.” It was only after moving to Life Unlimited and meeting Sanders Robb and Mary Sanders that his attitude began to shift. Sanders Robb shared her story about getting through painful times and turning the death of her best friend into a force for good.

“When you meet those kinds of people, it lifts up your spirit,” Powell says. “It gets to a point that you look at what life throws you, and if you are just there and complain, you are not going to go anywhere.”

With Sanders Robb’s encouragement, Powell started to work with troubled kids. He tried to inspire them and make positive changes in their lives. He launched his own nonprofit, the Nathan Powell Foundation (www.npfoundationinc.org), to support spinal-cord injury victims.

“Brittany has the purest heart and this amazing drive to help people,” Powell says. “She will do anything to help somebody.”

Sanders Robb’s charitable endeavors wound up charting a path that led her to Princeton. When she was in seventh grade, she was invited to Washington, D.C., to be honored for being the Missouri state winner of a community service award. At the ceremony she met Marsha Hirsch, the principal of Pembroke Hill, a prestigious private school in Kansas City. She wound up receiving a full scholarship, quickly emerging as a stellar student and standout on the debate team, a young woman who thrived in the rigorous academic culture, but was never defined by it, according to Mike Hill, her debate coach and mentor.

“Brittany is welcoming, inclusive — a friend to everyone,” says Hill, now the head of Pembroke Hill’s upper school. “There’s an authenticity about her that is [very rare].”

DURING HER SOPHOMORE YEAR at Pembroke Hill, Sanders Robb got a last-minute call from the Kansas City-based National World War I Museum and Memorial. One of the museum’s biggest events of the year, the Walk of Fame, was days away, and a brigadier general who was supposed to give the keynote address had backed out. A museum official who had gotten to know Sanders Robb because of her fundraising for veterans asked if she would be the speaker. She wrote a speech and stepped to the podium, with thousands of people packed onto the expansive lawn in front of her. Just as she was set to begin a gust of wind scattered her papers, so far and so fast they couldn’t be retrieved. Sanders Robb spoke for 20 minutes, extemporaneously.

Uncommon poise seems to be baked into her, and so is a fierce commitment to support people who might feel overwhelmed and overmatched, says Sara Schuett, executive director of the Missouri Association of Trial Attorneys. “One of the qualities that stands out to me about Brittany is that she is fearless,” Schuett says. “Robb & Robb takes on huge corporations on behalf of injured individuals and gets some of the best results in the country.”

The prevailing stereotype of a personal-injury attorney is an ambulance-chasing opportunist who pounces on human misfortune and posts massive billboards on interstate highways to drum up business. Sanders Robb didn’t set out to change that but doesn’t mind if it’s an unintended consequence. Robb & Robb doesn’t advertise or solicit business. Sanders Robb sees her work in pragmatic, human terms. People get in accidents, whether at work or in a car or aircraft. They suffer injuries. They get sick or hurt or even die, sometimes because of negligence, incompetence, or recklessness. She says she wishes nothing bad ever happened to anybody, and that Robb & Robb would have to find a new kind of law to practice.

In Udall vs. Papillon Airways, Airbus, Sanders Robb’s greatest satisfaction wasn’t so much the record $100 million settlement, but the fact that Philip and Marlene Udall’s six-year quest to make the helicopter industry safer had been successful. Papillon has retrofitted all the company’s helicopters with crash-resistant fuel systems, and recently Sanders Robb learned that Airbus has told tour operators it would cover the full cost of the retrofit. The FAA has mandated that all helicopters manufactured after April 5, 2020, must be equipped with a crash-resistant fuel system, no matter when the model of the aircraft was originally certified. It doesn’t bring back any of the five people who suffered a horrible death as the sun set over the Grand Canyon one afternoon in 2018, but it’s a start.

“Brittany was born to do something,” Mary Sanders says. “She’s done a whole lot already.”

Wayne Coffey is a freelance journalist and the author of more than 30 books. He lives in Sleepy Hollow, New York.

No responses yet