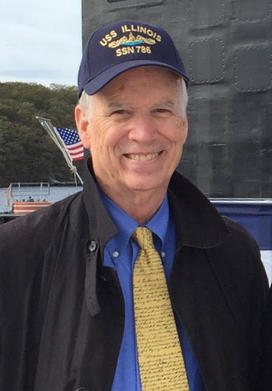

Scholar Michael Burlingame ’64 Searches for Truths About Lincoln

Burlingame has written or edited 20 books about Abraham Lincoln

After nearly two score years of Lincoln scholarship, Burlingame has an equally towering reputation in his field. Now 80, Burlingame has written or edited 20 books about Lincoln, including his influential 2,000-page, two-volume 2008 biography titled Lincoln: A Life. Last year he published two deep dives into Lincoln: An American Marriage: The Untold Story of Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd, detailing the woeful depths of their apparently loveless relationship; and The Black Man’s President: Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, & the Pursuit of Racial Equality, which explores the growth of the 16th president’s egalitarian spirit. The title refers to Douglass’ 1865 eulogy in which he said Lincoln was “emphatically the Black man’s president,” the first chief executive to treat each African American “not as a patron, but as an equal.”

Burlingame, nonetheless, acknowledges that early on Lincoln was a creature of his times. “By modern standards, he was certainly racially insensitive, to say the least, as a state legislator in the 1830s. But he didn’t stay that way the rest of his life,” says Burlingame. “In fact, as president — where words are really important — he came around to publicly championing Black citizenship rights, that is, voting rights, and got murdered for it three days later.”

Burlingame and a dozen other Lincoln scholars consulted with Steven Spielberg on his 2012 movie Lincoln. “It was basically accurate although with some details off,” he says. “But I think it missed the larger picture that that could have been drawn of Lincoln and his evolution with regard to race.”

“Why,” Burlingame asks, “did Lincoln despise slavery so early and so strongly?” He has an unexpected explanation. When Lincoln was a teen, his father, Thomas, rented him out to neighbors to toil as a farm worker, including splitting rails, work for which young Abe received no compensation. Burlingame reports that in the 1850s Lincoln told an audience, “I used to be a slave,” and he concludes that “Lincoln’s difficult childhood helped him to empathize with Black Americans better than many of his white peers.” A sign of the trauma the future president suffered, according to Burlingame, was his refusal to attend his father’s funeral.

“I think he unconsciously identified with many slaves, because his father was a slave owner. The evidence for that, of course, has to be mostly speculative,” Burlingame concedes.

A second key to understanding Lincoln’s compassion, according to Burlingame, lies in understanding the effect his home life had on him. Mary, who was likely bipolar and suffered from manic depression, made their marriage — in the words of Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon — “a burning, scorching hell.” Burlingame documents dozens of gut-churning episodes in which she throws scalding drinks on him, chases him with a knife, hits him in the face, subjects him to public tirades (including throwing herself on the ground), and misuses her position as first lady to sell political favors.

“It was a pretty depressing book to write,” Burlingame says. “You have to feel sorry for Mary. She is more to be pitied than censured. It’s a testament to his character that he tolerated her for so many years and in such a kind and forbearing way. You can’t appreciate Lincoln’s triumph over adversity unless you realize how difficult it was to take.”

Showing no sign of letting up, Burlingame has blocked out his next book: a study of Lincoln’s wartime support of the colonization of Haiti, Liberia, and Central America by former slaves. “It is grossly misunderstood,” says Burlingame, who now teaches remotely from his Mystic, Connecticut, home and is president of the Abraham Lincoln Association. “Lincoln viewed it as a humanitarian gesture for Blacks who understandably believed they would never get a fair shake in the U.S and wanted a haven.”

A self-described “classical music and opera nut,” Burlingame finds symbolic meaning in performances Lincoln attended. Before his inauguration, Lincoln attended Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera while in Manhattan. “It’s the only opera in the standard repertoire about the assassination of an American political figure. The Governor of Boston, as the libretto identifies him, is killed,” says Burlingame. In Washington, Lincoln attended Mozart’s Magic Flute. Its central character sings an aria about vengeance having no place in his realm. “George Bernard Shaw called it the only music that would not sound out of place in the mouth of God,” says Burlingame.

Burlingame is grateful for the years he has dedicated to researching Lincoln. “I identify with pianist Jonathan Biss, who specializes in Beethoven. He says studying him and playing his works not only makes him a better musician but a better person. I feel that way about Lincoln,” says Burlingame. “I feel ennobled by Lincoln.”

No responses yet