A Scientist in the Public Square

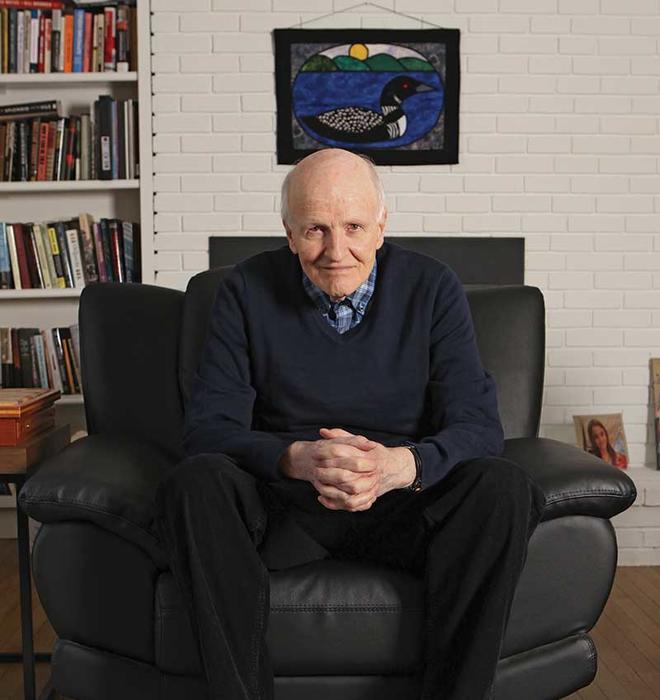

At 83, Frank N. von Hippel is still working to save the world

Moscow, 1987.

In the Kremlin’s parquet-floored Alexander Hall, a 49-year-old Princeton professor is addressing 1,500 foreign invitees and members of the Soviet elite, including General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev. The meeting is also being beamed live to a national television audience in the USSR.

“I would like to start with an old point — but one which scientific study makes ever clearer,” says Frank N. von Hippel. “The Soviet Union and the United States each possesses 10 to 100 times the destructive power that would be required to destroy either as a modern society.”

For the next 20 minutes, von Hippel lays out the framework for a massive reduction of nuclear weapons and why it made sense for both countries. “A surprise attack by either side would only succeed in reducing the total destructive power of the other by perhaps one half — an insignificant result given the levels of destructiveness that both would possess even after 90 percent reductions.”

Although he was representing the consensus of a contingent of international scientists, von Hippel could just as easily have been channeling the thoughts and fears of billions of people around the world who saw the growing stockpiles of doomsday weapons as madness.

Thirty-four years later, von Hippel calls that speech, which helped persuade Gorbachev to push for far-reaching nuclear-arms agreements, one of the most consequential moments of his career.

It has plenty of competition.

Von Hippel, now professor emeritus of public and international affairs, has spent more than 50 years trying to contain, secure, or banish the highly enriched uranium (HEU) and plutonium necessary to make nuclear weapons. At age 83 he remains actively engaged in educating government officials — and the public — about the dangers inherent in nuclear materials. He remains a critical voice in efforts to eliminate the chemical “reprocessing” in which plutonium is separated from the irradiated uranium used in nuclear power plants. He recently co-authored Plutonium: How Nuclear Power’s Dream Fuel Became a Nightmare, which spells out how plutonium could become more accessible “to countries and terrorist groups for the potential manufacture of nuclear weapons and for potential use in ‘dirty bombs.’” And by early February he had sent four memos to members of the Biden administration on topics related to nuclear materials and strategy. “I know people who know people,” he says.

“Frank has brought to public-policy discussions both a deep understanding of nuclear physics and a courage and imagination to question many mainstream policy views,” says Harold Feiveson, who along with von Hippel co-directed Princeton’s Program on Science and Global Security for 30 years. “He was among the most impactful scientists working with Soviet counterparts in unraveling the Cold War.”

Spend a couple of hours with von Hippel and you come away entertained by his jaunty anecdotes — and grateful that there are people like him dedicated to keeping the world from blowing up.

Von Hippel comes from a line of distinguished physicists. His grandfather was James Franck, who won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1925; his father, Arthur, was a professor at MIT credited with founding the field of materials science and engineering. (Enshrined in family lore is the story of how Franck, who was Jewish and emigrated from Germany in 1935 to escape Nazi persecution, deposited his gold Nobel medal with Danish Nobelist Niels Bohr. When the Nazis invaded Denmark in 1940, another colleague dissolved the medal to keep it from being confiscated; it was later remade in Sweden and returned to Franck in 1950.)

When it came time for von Hippel to choose a career, physics seemed like a natural path. He got his undergraduate degree at MIT and in 1959 won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University, where he earned his Ph.D. in theoretical physics.

Although he liked physics as a discipline, von Hippel was already beginning to question whether that was where he could make the biggest difference, he recalls. After postdoctoral studies at the Fermi Institute at the University of Chicago and at Cornell, von Hippel was hired as an assistant professor of physics at Stanford. It was there that he decided to abandon research in elementary particle physics to focus on informing policymakers about issues related to nuclear technology. “It seemed to me that maybe one in a thousand physicists were making important contributions in elementary particle physics, and I wasn’t going to be that one person,” von Hippel says.

At Stanford, von Hippel was inspired by the idealism of student activists who opposed federal funding for military research on college campuses. He began giving talks on the need for arms control. After one of them, a woman from the crowd approached him and asked why scientists continued to collaborate with the Defense Department on weapons technology. They chatted briefly: She was Joan Baez, a countercultural icon and antiwar activist whose songs became part of the soundtrack of the ’60s.

Von Hippel is full of stories like this.

Here’s another: In 1970, von Hippel collaborated with one of his graduate students, Joel Primack ’66, on a study about the efficacy of science advising in informing government policies. Their final report, “Scientists and the Politics of Technology,” concluded that scientific advisers were occasionally used as pawns to legitimize political decisions. Six months later, an Associated Press reporter wrote an article about the study that, in today’s parlance, went viral. It wound up on the front page of the National Enquirer — yes, that National Enquirer — under the banner headline: GOVERNMENT SUPPRESSED SCIENTISTS’ WARNINGS OF DANGERS.

The brief sensation caused by the report inspired von Hippel and Primack to collaborate on a book, Advice and Dissent, which advocated for greater transparency in the science advice given to elected officials.

Von Hippel knew he wanted to spend his life advising policymakers, but he wasn’t sure what that sort of career looked like. “The hardest thing was making the transition out of academic physics and finding a way into the policy world,” he says. “At that time, there was no beaten path. To the extent that it was done it was done as a sideline, and the government would listen to someone who had been involved with the Manhattan Project, for example.” But von Hippel wasn’t a famous scientist, so he worried that nobody would pay attention to him.

His big break came in 1974, when von Hippel joined an illustrious group of scientists — including Nobelist Hans Bethe — to produce a report by the American Physical Society about the safety of large light-water nuclear power reactors that were typical of those used in the United States at the time. In his typically self-effacing manner, von Hippel says he “lucked out” because his involvement in the study “made me look like an expert.” A few months later, he accepted a one-year appointment as a member of the research staff at Princeton’s Center for Environmental Studies.

Von Hippel joined the faculty in 1984 and began teaching an undergraduate survey course in science, technology, and public policy. Donald Lu ’88 *91 was one of his students. He describes von Hippel as an “amazing” teacher. “That experience inspired me to pursue a career working in the former Soviet Union,” Lu says, and led to a 30-year career in government service. He is currently the U.S. ambassador to the Kyrgyz Republic.

Von Hippel’s entrée into U.S.-Soviet arms negotiations stemmed from his chairmanship of the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), a think tank devoted to global security. He was invited to Moscow for preliminary discussions by Eugene Velikhov, an eminent Russian scientist who had the ear of a rising Politburo member named Mikhail Gorbachev. “The Soviets saw me as being much more important than I actually was,” von Hippel says.

At the time, tensions were high. After Ronald Reagan’s election as president in 1980, the United States embarked on an arms buildup aimed at countering what the administration viewed as Soviet superiority in nuclear strike capability.

Coupled with that was a belief among hawkish American officials that the Soviets believed they could fight and win a nuclear war. “There were people in the Defense Department saying scary things,” von Hippel recalls. “They said we have to convince the Soviets that we are willing to fight a nuclear war.”

The rhetoric and weapons buildup gave rise to the nuclear-freeze movement in the United States, which, according to von Hippel, became a powerful instrument in shaping public opinion and ultimately influencing policymakers on both sides.

Meanwhile, the Soviets believed the Americans wanted to destroy them, fears that intensified in 1983 when Reagan introduced plans to pursue the Strategic Defense Initiative. Dubbed “Star Wars,” it was designed to provide a dome of protection against incoming Soviet missiles. Although scientists dismissed the plan as unworkable and likely to fail, it solidified the view among Soviet hardliners that the United States was on a path to develop a first-strike capability. In what von Hippel calls “the closest we have come to nuclear war since the Cuban missile crisis,” NATO war games in November 1983 were so realistic they convinced some Soviet military leaders that an attack was imminent. “The Soviets started loading bombs on planes,” von Hippel says. The crisis was averted when the exercises, code named Able Archer, ended a few days later.

That scare coincided with the broadcast of the American television movie The Day After, which depicted the aftermath of a nuclear exchange between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Von Hippel was in Moscow for meetings at the time and was interviewed on Russian television about the film. Although the goals of the Russian scientists he was collaborating with were virtuous, von Hippel was wary about appearing to support the Soviet government. “We didn’t want to be used as Soviet propaganda,” he says. His basic message was that there could be no effective defense against nuclear weapons and that “this would be a good time to stop the arms race.”

By the time Gorbachev was named general secretary in 1985, von Hippel had become a trusted adviser in the arms negotiations, even though he had no official role. Gorbachev, with Velikhov’s encouragement, had implemented a unilateral ban on nuclear-weapons testing, hoping to convince the Americans that he was committed to curbing the arms race. “Velhikov used me to help Gorbachev legitimize his position” with Soviet hardliners, von Hippel says. “One of the important things that we did was to help Gorbachev keep going.”

At Velikhov’s request, von Hippel made a presentation to Gorbachev about how seismic detectors could irrefutably demonstrate that the Soviets were not secretly conducting underground nuclear tests, and thus help persuade the Americans to join the test ban.

In October 1986 Reagan and Gorbachev met for a two-day summit in Reykjavík, Iceland, to explore an arms agreement. The talks failed to produce a pact but set the stage for future negotiations. And four months later, von Hippel made his historic speech at the meeting of international scientists in Moscow, with Gorbachev in attendance. “That meeting was in part an effort to regain momentum after the Reykjavík failure,” von Hippel says. “My mission — although I didn’t fully understand it at the time — was to legitimize what Gorbachev and Reagan were saying about the need to end the nuclear-arms race by expressing the supportive views of the international scientists and to help bring along the Soviet public and the Politburo.”

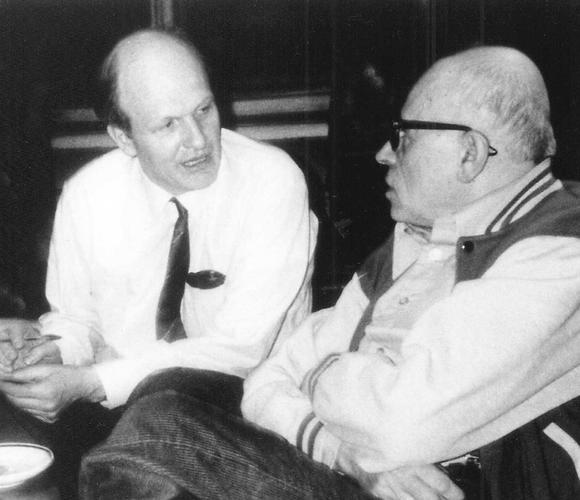

His time in Moscow also led to what von Hippel calls one of the most memorable evenings of his life. Andrei Sakharov was a Russian physicist who had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975 for opposing Soviet human-rights abuses and had been exiled to the closed city of Gorky in 1979 for speaking out against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Gorbachev had invited him to return to Moscow in late 1986, which caused an international celebration. Sakharov was scheduled to speak at the scientists’ meeting. He invited von Hippel and FAS President Jeremy Stone and their wives to his apartment on the eve of the meeting to discuss what he might say. “He was frail and had become unpretentious and dressed at home informally in what looked like a baseball jacket,” von Hippel recalls. “But he was intellectually unbending, ready to defend his positions against anyone.” Von Hippel later learned that the KGB, which had bugged Sakharov’s apartment, shared a transcript of their conversation with Soviet officials.

The gradual thaw developing between the Soviets and Americans enabled a growing sense of trust as arms negotiations continued. In December 1987 Gorbachev and Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) to eliminate all their short- and intermediate-range land-based missiles and launchers. (President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the treaty in 2018, citing Russian noncompliance.)

That pact was followed in 1991 by the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), which eventually eliminated roughly 80 percent of all strategic nuclear weapons.

“The breakthroughs were important, not in that they ended the danger from nuclear weapons — they didn’t,” von Hippel says. But they erased the belief on both sides that their opponents thought a nuclear war was winnable. “The Reagan-Gorbachev mantra, ‘A nuclear war cannot be won and must not be fought,’ was therefore perhaps the most important result.”

For von Hippel, the end of the Cold War posed a dilemma. “I was wondering, ‘What am I going to do now?’” The answer, as it turned out, was to pivot away from eliminating missiles to trying to end what he saw as the developing threat: the production of plutonium and highly enriched uranium, the materials upon which nuclear weapons rely. This continues to be his emphasis.

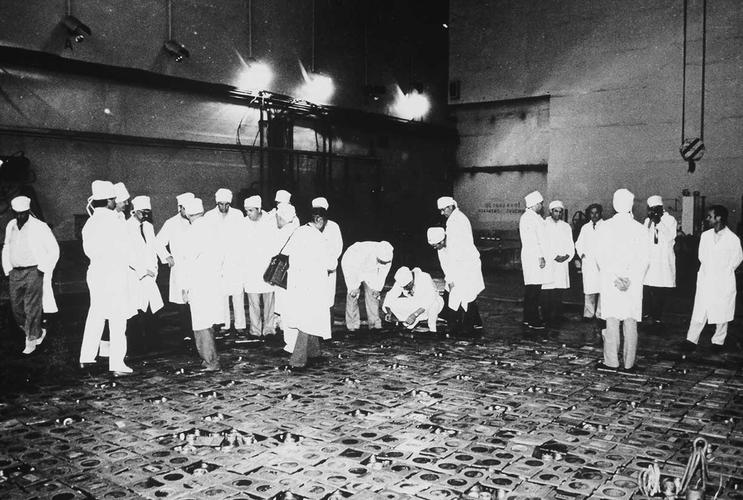

Von Hippel spent 16 months as assistant director for national security in the Office of Science and Technology Policy during the Clinton presidency, primarily focused on securing nuclear materials in the former Soviet Union. That position involved touring Russian facilities where HEU and plutonium were being used for civilian purposes. What von Hippel saw shocked him: for example, a lightly guarded, insecure nuclear laboratory where HEU was stored almost casually — “in a locker similar to a U.S. high school student’s locker.”

There is a lot of HEU and plutonium out there, von Hippel says — excess left over from mothballed weapons programs, and reprocessed plutonium produced by breeder reactors at nuclear power plants. Disposing of it or securing it safely is critical to avoid theft and misuse. Plutonium that has been separated is relatively easy to access and handle. “You could carry it around in a paper bag,” von Hippel says. It could therefore be easily stolen and repurposed for weapons manufacturing by bad actors. Colleague Hal Feiveson says von Hippel, “perhaps more than any other scientist, ... has shined a light” on these dangers and worked for the worldwide abandonment of nuclear reprocessing.

Nuclear weapons in the hands of rogue nations or terrorists are an ever-present threat, von Hippel notes, but what really keeps him up at night is the possibility of a nuclear launch caused by a misunderstanding or a malevolent hacker. “The danger isn’t that if we let our guard down one centimeter our enemies will attack us,” von Hippel says. “The danger is accidents.”

That vulnerability is more pronounced because of a defense posture that uses a “launch on warning” protocol, which puts a hair trigger on the nuclear button in a case where one side or the other might mistakenly believe it is under attack. Concern about that was the subject of one of von Hippel’s memos to the Biden team. (As of mid-February, he had not heard back.)

He also pushes back against U.S. approaches that he believes make nonproliferation diplomacy harder. One example is the Navy’s continued use of HEU to power its nuclear submarines. “That makes it harder to convince other would-be nuclear nations — Iran, principally — to stop their own enrichment programs,” von Hippel says. France uses low-enriched uranium that is not usable for nuclear weapons, he adds, “and we could, too.”

Von Hippel has written scores of papers over the years highlighting vulnerabilities and proposing solutions, and in 2006 he co-founded the International Panel on Fissile Materials, which aims to curb the production and use of HEU and plutonium. Whether he and his colleagues are winning is hard to say. On the positive side, von Hippel is surprised at the “relatively small number of countries” with nuclear weapons. “They’ve concluded that they’re safer without them,” he says.

And only a handful of countries are still reprocessing plutonium, though it could take another 20 years to get worldwide compliance. “I may have to live to be 100 years old,” von Hippel jokes.

But more than 1,300 metric tons of HEU remain in the world, about 90 percent of which is possessed by Russia and the United States — enough to make 50,000 nuclear weapons. The United Kingdom still has 115 metric tons of plutonium, but recently agreed to stop producing more. Progress has been frustratingly slow and “surprisingly hard,” von Hippel says.

What about North Korea? “I think we have to live with them for a while, until we can convince them that having nuclear weapons is not in their best interests. That might take another 20 years, too,” von Hippel says. He pauses, and grins. “Another reason for me to live to be 100.”

Freelance writer Kevin Cool is the former editor of Stanford magazine.

5 Responses

J. David Hohmann ’88

4 Years AgoDefinitely Among the Best

As this article shows, Frank Von Hippel has been a great example of Princeton in the highest services to humanity and the planet. His Princeton class that I took, entitled WWS 304: Science, Technology and Public Policy (in about 1986, right around the time of Chernobyl) was definitely among my favorites, a real privilege. As much as anything else from my time at P.U., it made a lasting positive impact on my path and life choices.

I believe that such a course should be required now for every science major if we are to find ways to forge a sustainable future through enlightened science and technology practice and policy. For the pace of science advancement continues to snowball, and too many science/tech workers may feel siloed. Our work with technology does not exist in a vacuum, and science related policy decisions large and small have a huge bearing on the kind of world we may inhabit, enhance and pass forward.

Thank you to Professor Von Hippel and to Princeton for elevating these kinds of efforts which are so crucial in the modern era.

stevewolock

4 Years AgoFor the Record

Joel Primack ’66’s class year was incorrectly identified in an April feature story about Frank von Hippel.

Kerry H. Brown ’74

4 Years AgoNuclear Power Generation

The cover profile of Frank von Hippel by Kevin Cool was a fascinating read about the intersection between science and policy. However, I was perplexed that I could not tell if von Hippel's grave concern about nuclear weapons and the reprocessing of plutonium extended to nuclear power generation (zero CO2). My brief read of the 1974 American Physical Society report mentioned in the article took a positive position on the safety of the actual production of electricity from nuclear power.

As Dr. Kerry Emmanuel of MIT and others have stated, if you are serious about real CO2 reduction, you have to be real serious about promoting nuclear power generation of electricity.

Philipp C. Bleek ’99

4 Years AgoDeeply Appreciated by Students, Peers

It was a pleasure to see Professor Frank von Hippel’s championing of nuclear safety and security appreciated (“The Happy Warrior,” April issue). As an undergraduate majoring in what we used to affectionately call Woody Woo, I was focused on market incentives in environmental policy. But after taking one class with von Hippel, and then another, I changed my professional trajectory to the one I’m still on today. As a professor working on nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons threats, bridging the academic, government, and think-tank worlds, I’m regularly reminded that not only does von Hippel “know people who know people,” as you quoted him saying, but so many of them also know — and deeply appreciate — him.

Vlad Sambaiew ’74

4 Years AgoA Major Intellectual Force

Congratulations on the excellent article about Dr. Frank N. von Hippel in the April edition of the PAW. It captured incredibly well his lifelong commitment to public service and, more importantly, to a world of nuclear sanity. Dr. von Hippel is a major intellectual force in this regard. He represents the best of Princeton in the nation’s service and the service of humanity.