Scientists Consider Parallels in Climate, Conservation, and COVID-19

Professor David Wilcove studies how humans can save wild animals and why conservation has proven so difficult

As governments and hospitals struggled to keep up with the evolving COVID-19 pandemic earlier this year, David Wilcove saw chilling parallels between the mounting crisis and his own effort to prevent the extinction of wild animals. Wilcove, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs, blends ecology and the social sciences to study how humans can save wild animals and why conservation has proven so difficult. In February, he wrote at the news site Mongabay about how deforestation and the wildlife trade play into extinction and the COVID-19 pandemic; this summer, he and fellow conservation scientists published a perspective in the journal Current Biology about why human institutions struggle to respond to both. Wilcove spoke to PAW about the links between these global problems and a third crisis: climate change.

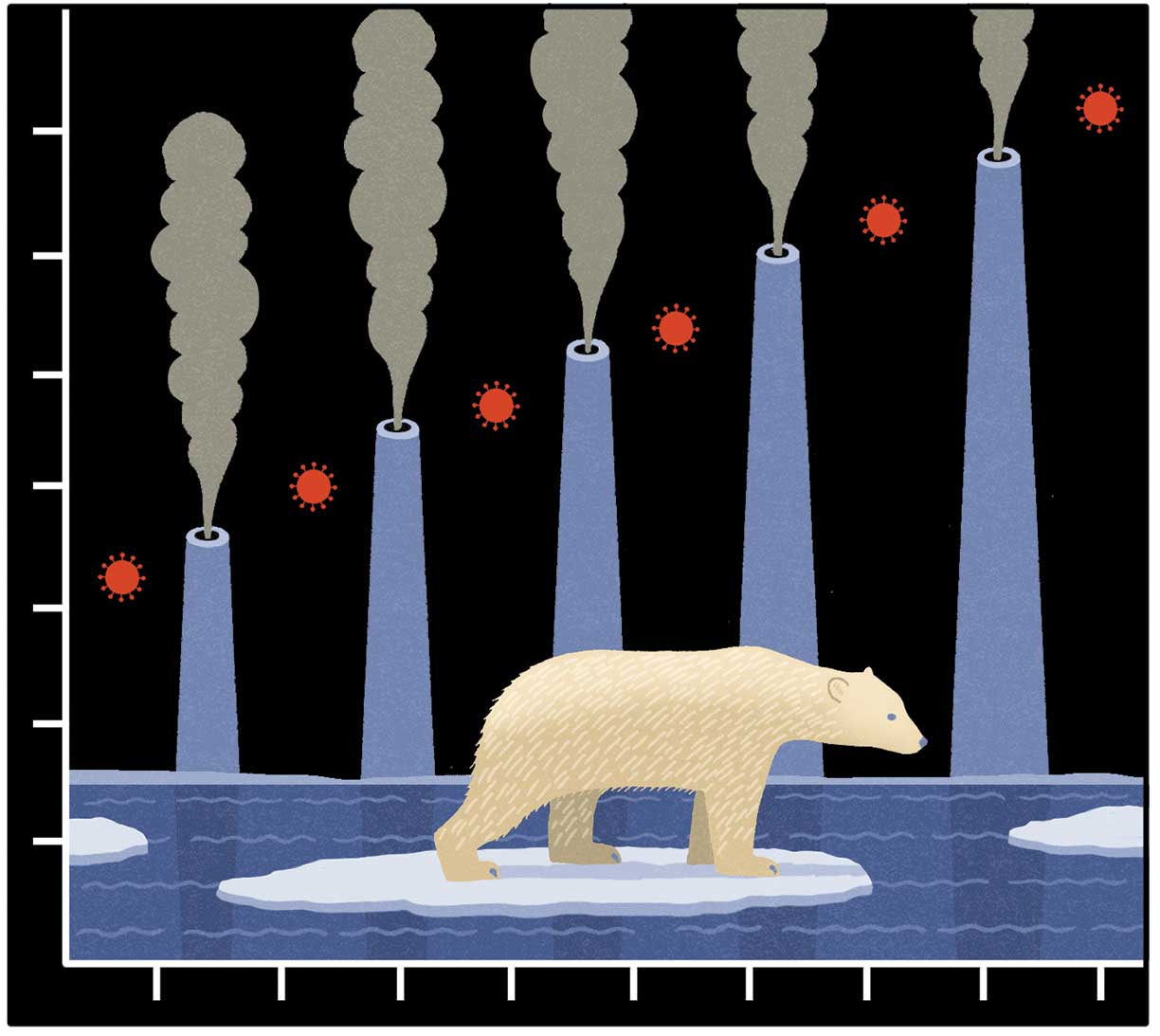

How did you and your colleagues come to see the connections between COVID, wildlife conservation, and climate change?

As the scope of the pandemic — and the difficulty of responding to it — became clear, my colleagues and I began to exchange emails. It was my co-author Andrew Balmford who first said, basically, “Hey, don’t a lot of the things happening now, in response to the COVID pandemic, remind you of why we are so frustrated about current attempts to address climate change and the extinction crisis?”

What parallels stood out?

There were three parallels among these three crises that we saw. The first is that all of them involve positive feedback loops: Things deteriorate at an accelerating rate, especially after you reach certain tipping points, as when COVID started spreading internationally or when a wild animal’s population dips below a viable threshold. In the case of COVID, this means exponential growth in infection rates, where a few cases could turn into a few thousand in a matter of weeks. I think the COVID pandemic has, for the first time, made a lot of people conscious of just how dangerous exponential growth can be, that a problem can go from minor to extremely serious in a frighteningly short amount of time.

The second is that there are time lags built in between an action — emitting greenhouse gases or transmitting the virus — and its consequences.

Finally, if you ignore the science, you cannot treat the problems. You can’t push them away, you can’t tweet them away, you have to understand the consequences and respond accordingly. But because of these first two problems, policymakers may not pay much attention to the science, at least at first.

You write that “even examined in narrow financial terms,” ignoring COVID or climate change for the sake of economic growth is more expensive than responding immediately. How do you get people to pay attention to the science when it means a short-term sacrifice?

This is where understanding the social science of conservation — economics, psychology, and sociology — is so important. It helps us understand how people behave, and how they change their behavior.

First, it can help us find a problem earlier and sound the alarm. For instance, in Southeast Asia, we discovered that monitoring the number of birds being sold in the market and their price can clue you in as to which species are being dangerously exploited, at a fraction of the cost of in-depth censuses.

Second, it can help you find a feasible solution. We know in my group that any solution has to be scientifically sound, economically feasible, and socially accepted, so there’s rarely a silver-bullet solution that works everywhere. This requires a change of mindset for scientists, because we value things that can be generalized. But if you think creatively, you can tailor a solution to the local context.

For instance, advocacy by celebrities like [former basketball star] Yao Ming made shark fin soup less socially acceptable to young people in China, reducing consumption to a fraction of what it was before. Or, as another example, my research has shown that forests in Malaysian Borneo still maintain the vast majority of their species after being logged. That enabled the government to protect many species by preserving millions of acres of already-logged forest, far more cheaply than preserving virgin forests.

What tools from the social sciences have you found particularly useful?

Since solutions have to be economically feasible, I’ve had the good fortune to have many wonderful economists in my research group over time. But we also use methods from sociology and anthropology — for instance, for interviewing people about sensitive topics — to get a better understanding of things people may be hesitant to talk about, like illegal sales of wild-caught birds.

Once you’ve identified a possible solution, how do you see your role as a scientist in ensuring that solution comes about?

As we wrote in Current Biology, the climate, COVID, and extinction crises don’t just have common features of the problem, they have commonalities in terms of their solutions. Decision-makers have to listen to the science, but solving any of these problems isn’t purely a scientific matter. It’s a social and political matter.

Many of the people in my lab will tell you about the grueling experience of giving practice talks to the group. It can feel like the Spanish Inquisition, but it’s intended to enable them to speak clearly and effectively: Scientists have to speak clearly to people, acknowledging their uncertainty but also the seriousness of the problem and the consequences of delay. So in everything that my lab does, both in scientific publications and presentations to the public and policymakers, we avoid jargon whenever possible, strive to present the information in a clear and convincing manner, and try to get it into the hands of interest groups and decision-makers.

The thing is, this has to happen everywhere. You can’t solve the COVID-19 pandemic in just one country, and similarly, all the world’s countries have to participate in saving wildlife and in bringing greenhouse gases under control.

Interview conducted and condensed by Bennett McIntosh ’16.

No responses yet