Stephen Lamberton ’99 Is Fighting a Stigma By Telling His Story

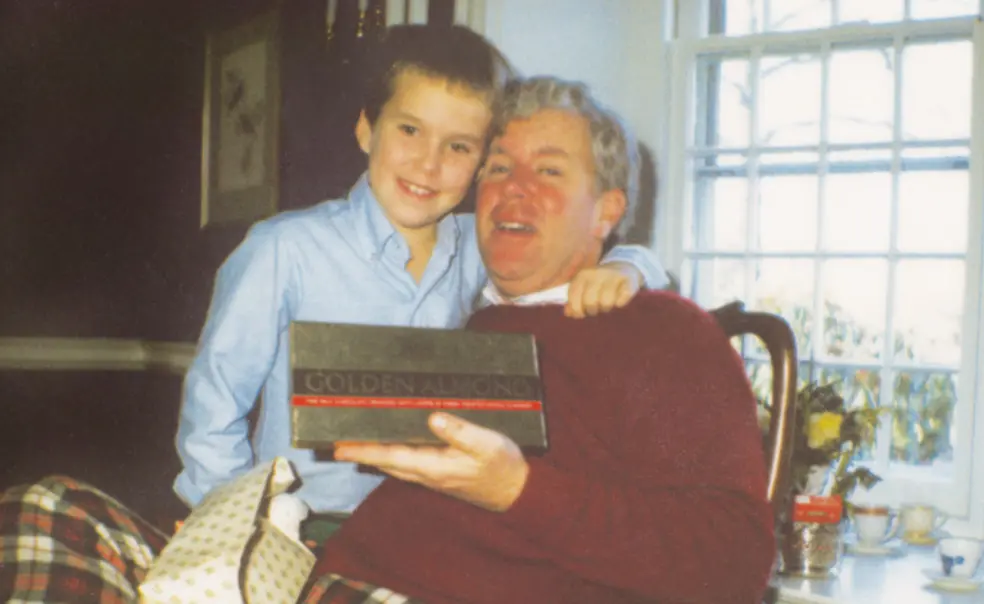

When he was 8, Stephen Lamberton ’99 lost his father, Robert E. Lamberton ’66, to suicide

If you or anyone you know needs help, you can reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988, and you can text the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

When Stephen Lamberton ’99 was 8 years old, he lost his father, Robert E. Lamberton ’66, to suicide. Today he volunteers with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and on the latest PAWcast he shared his story of healing. The following excerpt has been edited and condensed; the full conversation can be found online here or wherever you get your podcasts.

The now of my story is I’m almost 48 years old, a father of four, a husband, a professional, a volunteer with AFSP, and someone who’s a suicide loss survivor.

My father’s death by suicide was a health outcome, but being able to have that perspective on it has taken a while. It’s very helpful for me to share my story, and I hope that people will start to have a realization and an understanding about suicide which destigmatizes it and makes it easier to talk about.

I had a perspective, when I first had children, that I wasn’t going to tell them about how their grandfather died. I didn’t like talking about it with anyone, and I had a fear — I felt like if they knew someone in their family had died by suicide, that they’d somehow be more likely to die by suicide. And so, much like I did in other parts of my life, I avoided talking about it with them.

Now, that didn’t mean that it didn’t come up and wasn’t a factor, because it very much was. It impacted the way I interacted with them. And it wasn’t until my older son was 8, three years ago, that I was like, whoa, that was the age I was when my father died. That is very young. I was sort of proud that I was a father to them, which I hadn’t had, but also at times it made me resent them, because they would do perfectly normal things and I would react with a little bit of, “How dare you not be more grateful because you have a father and I didn’t.”

I came to the realization that I thought I was shielding them, but really it just was building up this resentment. That led to the process of telling them, and that really was the inflection point.

The example I now give, as I’ve thought through this, it’s as if I lived in a house and in some corner of the house there was a lava pit of doom. And someone said, don’t let the lava pit of doom define you. And so there’s two interpretations of that. You could never go in the room with the lava pit and eventually move out of the house. Or you could study the lava pit of doom, learn everything you could about it, so that you can interact with it with ease and know exactly what it was going to do and be safe from it.

For the last 20-some years since we graduated, my father wasn’t available to me because I hadn’t really processed it. It was only being back for our 25th reunion that I was able to be aware of the fact that this is something my father didn’t do. He died before his 20th reunion.

I had now lived and accomplished something that he hadn’t at Princeton, and that was very impactful for me. He never got this jacket. It’s kind of the most expensive jacket I have in some ways, but also the most valuable. So when I have a chance to wear it, I will wear it.

No responses yet