Strawberry Fields Forever

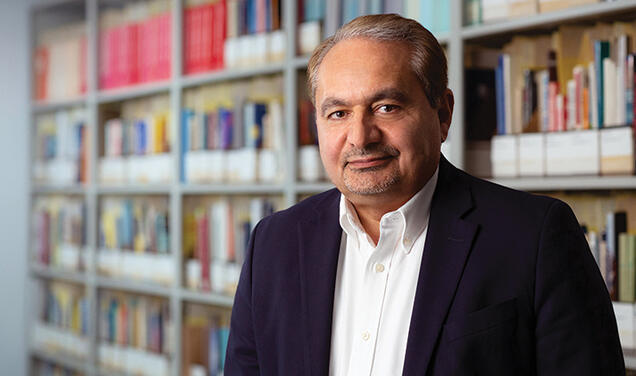

Miles Reiter ’71 has devoted his career to growing better berries and turning Driscoll’s into a leader in sustainability

One must ask children and birds how cherries and strawberries taste.

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Or one could ask Miles Reiter ’71. A fourth-generation farmer, he is the longtime head of Driscoll’s, the country’s largest seller of fresh strawberries — as well as raspberries and blackberries — and a growing player in the blueberry market. Reiter stepped down as CEO of the family-owned company on Jan. 1 after 23 years at that post in two separate stints but will continue to serve as executive board chair. He has a businessman’s eye for the bottom line, but he also knows what he likes on his cereal in the morning.

“It’s hard to care about the consumer experience if you’re not one yourself,” he reasons.

Given its market share, few have done more than Driscoll’s, and to a certain extent Reiter personally, to determine the availability, flavor, and even appearance of berries that end up in America’s fruit bowls. Working with growers in 22 countries, they sell berries on every continent except Antarctica. According to a study prepared for a Purdue University food and agribusiness summit in 2017, Driscoll’s transports more than a billion pounds of berries annually to more than 400 customer locations. And although they may not notice it, Reiter says that U.S. consumers who buy their strawberries year-round probably consume 15 varieties over a 12-month period, and five varieties of raspberries, as the supply shifts with the seasons.

Thanks in large part to Driscoll’s, which is headquartered in Watsonville, California, between Santa Cruz and Monterey, berries are booming. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, per capita consumption of strawberries and blueberries has more than doubled over the past two decades, while raspberry consumption has risen nearly threefold. Although Driscoll’s keeps information about its market share close to the vest, Reiter estimates that strawberries account for about 37% of its American sales, while raspberries account for about 30%, blackberries 20%, and blueberries 13%. Driscoll’s has more than $3 billion in annual revenue, according to Forbes, and is one of the top 25 American food brands in terms of sales.

Inevitably, any story about agriculture these days must address climate change. Warming temperatures and greater climate volatility are shaping how Driscoll’s grows and where, and how it packages its fruit. As one of the largest agricultural entities in California, it has advocated for new ways to conserve and reuse groundwater, also pledging to make its plastic packaging fully recyclable.

“Our mission is to continually delight our customers through alignment with our customers and growers,” Reiter says, reciting the company mission statement. One hears the same phrase from other Driscoll’s employees. It’s ingrained in them. What they mean is, the business is a three-legged stool composed of the people who develop the berries, the people who grow them, and the people who eat them — us. But the word that jumps out is “delight.” Ultimately, none of it matters unless the berries taste good.

To an older generation of Americans, there are few sadder words than “January strawberries,” conjuring memories of hard, pale, tasteless orbs. As for January raspberries or blackberries, they were just as bland — if they could be found at all. Reiter, who grew up in Watsonville in the 1950s and ’60s, speculates that he never had a fresh blueberry before he got to college because they simply weren’t commonly available in California. But thanks to the development of new varieties, wider sourcing, and an extensive distribution network, Driscoll’s can now ship berries anywhere in the country, and indeed across most of the world.

Beyond year-round availability, today’s berries differ from those a generation or two ago in other ways. “The older varieties were definitely smaller,” Reiter says, taking the strawberry as an example. “They probably had more random shapes. They would almost for sure have been softer.” Suggest that they were tastier, though, and Reiter pushes back, dismissing that as a trick of memory. “People say they were better back then, but a lot of that is going way back when there were still a lot of local berries.”

Farmstand berries may indeed be sweet, but they are smaller than the varieties Driscoll’s sells in supermarkets, have a shorter growing season, a shorter shelf life, are more prone to disease, and would turn to mush if shipped in volume over long distances. Driscoll’s has developed berries that are more uniform in appearance, higher yielding, more disease resistant, and easier to pick, saving time and money. Still, a hardy berry is not necessarily a tasty berry. To ensure that they are also delicious, Driscoll’s uses near-infrared sensors to measure the sweetness of its berries, known as the Brix level, but also relies on customer feedback and a volunteer advisory panel.

Consumer expectations have changed over the years. The blueberries increasingly found in supermarkets now, for example, are more oblong than round, full of flavor but with thicker skins that make them more durable. Strawberries are also firmer, almost crunchy at first bite. In consumer surveys, Reiter says, older buyers were less enthusiastic about firmer strawberries, but younger ones preferred them because that’s what they had become used to.

Different markets, in other words, different palates. Europeans prefer their strawberries softer, while Asians want them sweeter — a little too sweet for Reiter’s taste, though the company is working to develop a variety that meets that demand. The process works both ways, though. Raspberries and blackberries were all but unknown in China when Driscoll’s began selling there a decade ago, so the company has helped define an entire nation’s expectation of how they should taste.

Watsonville, and the surrounding Pajaro Valley, offer almost perfect conditions for growing strawberries: sandy soil, warm, sunny days, cool nights, and the right amount of rainfall. Most of Driscoll’s strawberries and raspberries are grown in Watsonville, Santa Maria, and Oxnard, California, as well as in Florida and Mexico. Blueberry and blackberry production is less centralized. Though much of it occurs in California, there are also large growing areas in locations ranging from the Pacific Northwest to Georgia, North Carolina, and South America.

Unlike bananas, berries don’t continue to ripen after picking; they’re as sweet as they’re going to be when they come off the plant. Getting them into stores quickly is important, so most are shipped by truck or air. Only blueberries are tough enough to go by boat. Reiter estimates that a container of Driscoll’s strawberries bought in Princeton would probably have been picked no more than a week ago.

According to lore, Driscoll’s traces its roots to the 1880s and a single strawberry plant found on a ranch in the Sacramento Valley, about 100 miles north of Watsonville. The strawberries it produced were so large, uniform, and sweet that the rancher, Thomas Loftus, dug it up and kept it alive in a barrel over the winter, eventually breeding about a quarter acre of plants. In 1900, two other farmers, Joseph Reiter (Miles’ grandfather) and Dick Driscoll, learned about Loftus’ berries and went into business with him. With an eye toward branding from the outset, they wrapped each crate with blue paper banner stamped with a red strawberry. Sales were so brisk that the strawberries became known as Banner berries because of the packaging.

In 1904, Reiter and Driscoll began growing Banner berries on their own in Watsonville, forming a partnership at Cassin Ranch, which still houses Driscoll’s research and development facility. Strawberry production fell on hard times during World War II. The Banner berry succumbed to disease, and many Japanese berry farmers in the area were taken to internment camps, leaving the Reiters and Driscolls among the few remaining growers in the market. In 1944, the two families established The Strawberry Institute to develop new varieties of strawberries and, when the war ended, rehired many of the Japanese growers. “I think very few people know about the Driscoll family,” World War II veteran Lawson Sakai told the Japanese American newspaper NikkeiWest. “They were lifesavers.”

Driscoll Strawberry Associates was founded in 1950 as an independent cooperative, later introducing the Z5A, a patented variety that had a longer growing season and could be shipped to distant markets. It merged with The Strawberry Institute in the 1960s, and shipments were united under the Driscoll’s label beginning in 1970.

Growing up, it was always assumed that Reiter would join the family business, but both he and his parents first wanted him to get a well-rounded education. As he recalls it, he wrote to several eastern colleges, and Princeton replied first. He majored in history and wrote his senior thesis on Spanish fiestas. Few other Princeton students, then or now, came from a similar background. “Being a farmer was an anomaly, for sure,” Reiter says. In fact, he recalls knowing only one other student, in a different class, who came from a farm family. (His sister teasingly suggested that they band together and call themselves the Princeton Farming Society.) Upon graduation, while most of his classmates headed for graduate school or the corporate world, Reiter returned to Watsonville.

Although his father ran the company, Reiter began at the bottom, hauling berries, running spray rigs, and driving tractors. He developed a talent for laying out strawberry fields, where the rows needed to be absolutely level for a hundred yards or more lest they flood when irrigated. “Those first four to five years were really valuable,” he says. Tragedy accelerated Reiter’s advancement in the company when both his parents were killed in a plane crash in the late 1970s. At the age of 38, he took over Driscoll’s operations in central California, while his younger brother, Garland, ran them in Southern California.

When Reiter became board chair in 1988, he faced a crossroads. Three of Driscoll’s’ largest competitors in the strawberry market offered to buy the company out. Rather than sell, Reiter decided that Driscoll’s needed to expand to survive. He added raspberries, blackberries, and blueberries to their product line, making Driscoll’s the only major American fruit grower to sell all four berries, and in order to have a supply of fruit year-round, he found new growers in Mexico and South America. Driscoll’s has since expanded into Europe, Australia, and Asia, as well. Reiter became CEO in 2000 and, after stepping aside in 2015, returned to that post in 2018.

One curiosity about Driscoll’s is that the company handles every step of berry cultivation, from seed to shelf, except actually growing them.

Company agronomists study the berry genome, developing varieties that are then bred at a nearby nursery. Once the seedlings have enough of a root structure to survive, they are shipped to licensed, independent growers, who plant them, weed them, water them, and pick them.

For nonorganic fruit, Driscoll’s says that its growers abide by all guidelines from the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration. It adds that growers rely on an Integrated Pest Management approach, which the EPA calls “an effective and environmentally sensitive approach” that seeks “to manage pest damage by the most economical means, and with the least possible hazard to people, property, and the environment.”

All four types of berries are picked by hand and placed in plastic containers, known as clamshells, which Driscoll’s supplies. It is a point of pride that every berry one finds in the supermarket was last touched by the person who picked it. Driscoll’s contracts with nearly 1,000 growers worldwide who collectively employ well over 100,000 people. Although growers are responsible for hiring their farm labor, Driscoll’s requires everyone it works with to adhere to fair labor standards and says that all fruit coming from Mexico is Fair Trade Certified.

Once clamshells are loaded in the field, Driscoll’s collects and distributes them, but there is one more intermediate step. Berries are very sensitive to heat and are likely to degrade if they encounter sharp temperature swings in transit. To fortify them, the company sends all of its berries to cooling plants where they are chilled to just above freezing for 24 hours. Only then are they sent to buyers around the country.

BERRIES ARE A DELICATE FRUIT, and so are particularly susceptible to climate change.

Although rising temperatures are not likely to threaten production in California, at least in the near term, Driscoll’s has begun to explore new areas for growing, such as Ontario and Quebec. A related concern is that the weather has become less predictable. It doesn’t rain when it should or rains too much when it shouldn’t, which raises costs and sometimes forces the company to scramble to ensure a steady supply.

“Climate volatility is driving us crazy,” Reiter says. “If we breed [plants] for more tolerance for heat or rain resistance, what you lose is the likelihood of getting the other traits you really value, like flavor.”

Driscoll’s has responded with an initiative called More Berries With Less Resources. By that they mean reducing the use of all kinds of resources, including fertilizer and labor. But the greatest concern is water.

“We have water issues almost everywhere we farm, even Florida,” Reiter says.

Driscoll’s has focused on curbing water use and maintaining water quality in all its growing regions, joining the AgWater Challenge, a collaborative effort by the sustainability nonprofit Ceres and the World Wildlife Fund that required participating companies to meet water use standards by 2020. In Oxnard, nearly two-thirds of growers now use micro sprinklers, which can deliver smaller amounts of water efficiently, while soil moisture sensors ensure that plants are watered only when necessary. Strawberry beds have protections built in to minimize runoff, while raspberries and blackberries are largely grown in pots rather than directly in the ground, also to save water.

In 2014, California enacted a series of laws known collectively as the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), requiring localities around the state to form agencies and develop plans to manage water use. Among the provisions that have been enacted in the Pajaro Valley, companies now pay a hefty fee for groundwater, up to $400 per acre-foot, making it “essentially a tax on water,” according to a 2023 article in The New York Times. Reiter was an early proponent of the SGMA, in part because Driscoll’s was already part of the Pajaro Valley Community Water Dialogue, a group of growers, landowners, and government officials who meet to coordinate conservation efforts. Independently, Driscoll’s has also joined with researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz in a project to capture and divert stormwater to the aquifer.

“I do think they have been pioneering in understanding that the future of their company depends upon sustainable groundwater management,” says Jay Famiglietti *92, a professor at Arizona State University who has studied aquifer depletion in California and around the world. (See “In A Dry Country,” PAW March 16, 2016.) “Driscoll’s has exactly the perspective that all agriculture companies and farmers should have, that there is no way to sustain groundwater if it’s free.”

Reiter, who has also advocated for a carbon tax to address climate change, agrees that water conservation efforts will likely lead to higher food prices. “A low percentage of income goes to food in the United States, and that number will have to go up,” he believes. “When it’s unreliable, it’s more expensive.”

On a pilot basis, Driscoll’s has even begun to look at growing berries indoors. This winter, it began working with a startup called Plenty Unlimited Inc. that grows lettuce, spinach, and other produce without natural sunlight or even natural soil, a practice known as vertical farming. These and other innovations have been featured by the Environmental Defense Fund, which called Driscoll’s “a leader in water conservation.”

Another large environmental concern is reducing the use of plastic packaging. That strikes a particular chord at Driscoll’s because the company helped invent plastic packaging for its berries. Back in the 1980s, it began selling them in distinctive yellow plastic baskets to promote brand recognition. The clear plastic clamshell, which Driscoll’s introduced in 1994, was revolutionary at the time because it protected the berries while allowing airflow that reduced mold. Because Driscoll’s berries are packed in the field, the green paper containers one often sees at farmstands are impractical because they don’t have tight lids and fall apart if they get wet. Sturdier paperboard containers, which the company recently began using in Europe, have not yet been introduced widely in U.S. markets.

In addition to being a member of the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, which requires companies to put recycling instructions on all packaging, Driscoll’s became the first American produce company to join the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, a partnership between the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the U.N.’s environmental agency, to reduce its use of plastics. Reiter says Driscoll’s remains committed to having fully recyclable packaging, including labels, by the end of next year.

ACROSS THE COUNTRY, family farming has been under threat, but at Driscoll’s, the next generation is already in place. Reiter’s daughter, Brie Reiter Smith, spent several years growing blueberries for Driscoll’s in Chile and is now back in the U.S. as vice president of product leadership. His three other children, as well as several nephews, are also involved with the company in various capacities.

Though he has handed off responsibility for day-to-day operations, Reiter intends to remain involved with the business, possibly focusing on new markets and growing areas. In semiretirement, he also hopes to travel, fly fish, and give more attention to his garden at home. “You learn things in the vegetable garden,” he observes, one of which is that while strawberries may love the cool temperatures around Watsonville, his backyard tomato plants do not.

In his early years with Driscoll’s, straight out of college, Reiter drove a tractor and was out in the fields every day, experiences that continue to shape his outlook. One thing he has preached throughout his career is that growers should not set their plants too close together. Crowded fields may yield a slightly larger crop, but the berries will receive less sunlight and won’t be as sweet.

“I still have pretty strong points of view about how these plants should be grown,” he says, driving across the valley outside Watsonville. In mid-January, the strawberry plants are still only green, but in a few weeks, spring will come, and they will be dotted with almost unimaginable numbers of sweet red berries for as far as the eye can see.

“Lots of things have changed,” Reiter says of his years in the berry fields, “but you still have to get it right.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

1 Response

Debra H. Bradley

9 Months AgoAn Industry Genius

Great article. Miles is a lot more than the CEO of the company. He’s the genius — on so many levels — of product and Driscoll’s impact on the global industry. He’s a polymath: He can understand technical/emotional state of the grower (so important), genomics and molecular composition of berries (not easy, a strawberry is an octoploid), and most importantly, how to sell and create a loved brand. Legend!