A tale of two charters

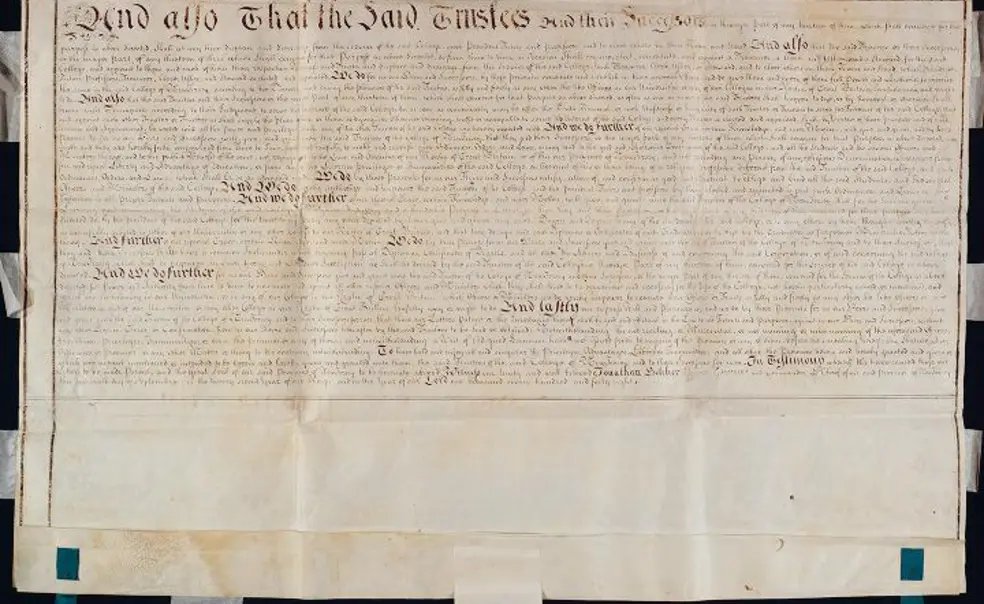

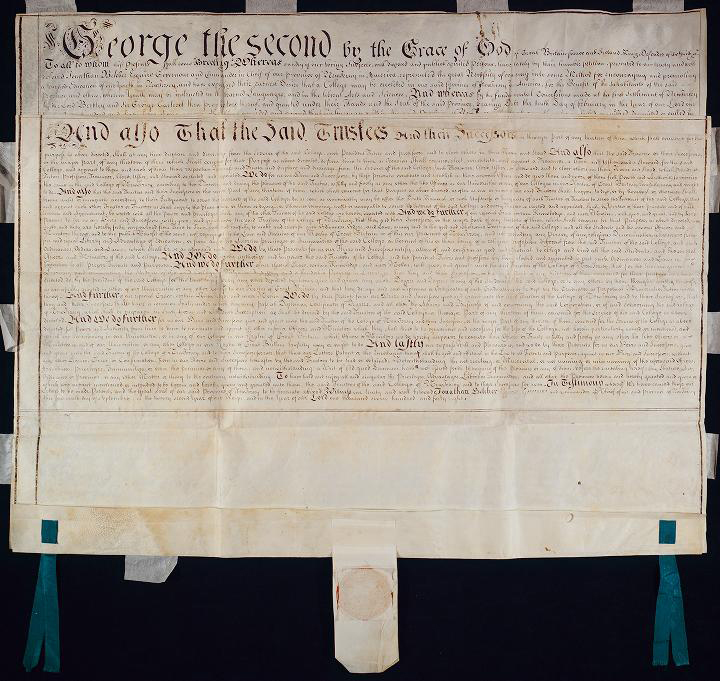

Second charter of the College of New Jersey, 1748 (Courtesy Princeton University Archives)By Martha Vega-Gonzalez â09This is the first article in an occasional series about Princeton history and the University archives at Mudd Library. Vega-Gonzalez, a recent graduate who majored in history, lives and works in New York City as a freelance writer. Last weekend, the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library put the University charter on display for the third and last time this year. The last time the charter was displayed before that was in 1996, and there are no plans to exhibit it again in the foreseeable future -- so if you missed it this time, it may be a very long time before you get another chance to see it. But if you would like a closer look at Old Nassau's founding document, never fear: Photographs of the charter are easily accessible and a full transcript of the charter is available in Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker's Princeton, 1746-1896.

The most interesting thing about the charter on display is that it's not the University charter, as much as it is a University charter. The charter on display dates to 1748, but as every Tiger knows, the University dates itself to 1746. Indeed, the charter housed in Mudd is the second University charter, which was drawn up after Anglican critics of the Presbyterian institution claimed that John Hamilton, serving as interim governor after the death of Governor Lewis Morris, had overstepped his bounds when he issued the original charter; to resolve all doubts about the University's legality and legitimacy, new Governor Jonathan Belcher issued a second charter in 1748.

This new charter was similar to the old charter (a discussion of the substantive differences can be found here, and both texts are available in Wertenbaker's book), serving as an effective constitution for the College of New Jersey (which was officially renamed in 1896). The charters created the College, giving it the official patronage of King George II, and proclaiming the loyalty of the College to the King.

Seizing on the spirit of the New World and highlighting Princeton's origins as a dissenting institution, the charters also proclaimed the religious freedom of students (though, a later reference to "popish recusants" calls into question how far those religious freedoms extended to non-Protestants). Ultimately however, the charters were intended to detail how the school would run, providing the rules by which the trustees could acquire and dispose of property, appoint persons, and generally operate the college.

Sadly, the original 1746 charter is lost to time. For over a hundred years the text of the 1746 charter was also believed to be lost, forcing Princetonians to speculate about its contents, but a transcript was eventually unearthed in the library of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in London. Who knows? Maybe someday the 1746 charter will be found as well. In the meantime, unfortunately, it seems far more likely that the 1746 charter will be featured in a historical adventure novel than in an exhibition at Mudd.

One additional fun fact: The College of New Jersey was the brainchild of Jonathan Dickinson, Ebenezer Pemberton, John Pierson, Aaron Burr Sr., William Smith, Peter Van Brugh Livingston, and William Peartree Smith -- six Yalies and a Harvard son who apparently thought the world needed a better university.

No responses yet