These Princeton Professors Are Researching COVID-19

University researchers are examining viral load, asymptomatic carriers, and more

Princeton professors across disciplines are researching several aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Here’s a sampling of the work being done.

The National Science Foundation’s Rapid Response Research program, which is designed to marshal scientific talent in the face of emergencies, has awarded four grants to Princeton researchers working on various aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

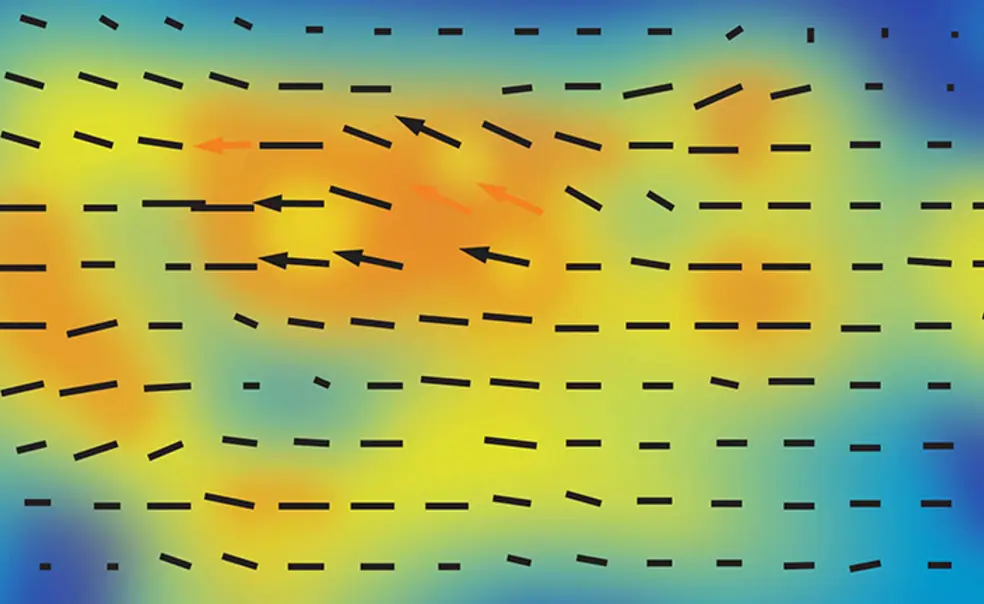

Mechanical and aerospace engineering professor Howard Stone is investigating the movement of aerosol particles released through human speech, laughter, and breath, especially in asymptomatic hosts, using his background in fluid mechanics.

Kyle Jamieson, associate professor of computer science, is working to develop a system that uses cell-phone data to help public-health officials track those diagnosed with diseases like COVID-19 without compromising users’ privacy.

Vincent Poor *77, an electrical engineering professor, is expanding a mathematical model measuring how a virus’s mutations and human interventions affect the spread of a disease. Such a model could allow public-health officials to better anticipate the effectiveness of measures such as social distancing.

Professor of psychology and public affairs Alin Coman is investigating how a person’s level of anxiety influences how they share and learn information about the COVID-19 pandemic. Coman will look at whether, for example, someone with a high level of anxiety is more apt to spread misinformation about the disease.

Professor of chemistry and genomics Joshua Rabinowitz and genomics research fellow Caroline Bartman penned an April op-ed in The New York Times that discussed what they see as a missing factor in the COVID-19 discussion: viral load. The authors point out that the amount of exposure to a virus can determine the severity of its impacts on one’s health. Just as a tiny dose of a smallpox pustule creates a survivable illness and inoculates those receiving it, Rabinowitz and Bartman argue, epidemiological models should further explore the effects of low-dose exposure to the virus that causes COVID-19. They also emphasized the need to protect those encountering high doses, such as hospital workers and public-transit users.

A Princeton study published May 8 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences examined the evolutionary advantages of a virus that relies on symptomless transmission — like SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19. While a silently spreading virus has the benefit of wide transmission by an unwitting host, oftentimes asymptomatic carriers produce fewer infectious particles. Using a modified mathematical formula, study authors Chadi Saad-Roy GS and Princeton professors Simon Levin (ecology and evolutionary biology), Bryan Grenfell (ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs), and Ned Wingreen (molecular biology and genomics) found that despite the drawbacks, asymptomatic transmission is a successful evolutionary tool for a virus’s long-term survival.

Adam Elga ’96, professor of philosophy, co-authored an April op-ed in Route Fifty, an online news organization for state and local leaders, about how a shortage of ventilators in hospitals is a result of a human tendency to systematically underestimate the possibility of cascading system failures. Drawing from his 2018 article for the journal Behavioural Public Policy, the op-ed lays out how forces such as cost cutting, competition, and human bias discourage potentially costly preemptive measures, such as maintaining a large medical stockpile, which leads to a tendency to underestimate the impact of a system failure. However, Elga says his research revealed that decision-makers who were more educated about the risks of being underprepared were willing to invest more to avoid system failures.

Jacob N. Shapiro, co-director of Princeton’s Empirical Studies of Conflict Project, and a team of researchers are collaborating with Microsoft Research to combat online misinformation about the coronavirus pandemic. Shapiro, who is also a professor of politics and international affairs, is leading a global team of 16 undergraduate and graduate students from Princeton and three other universities. Together, they have created an online database of false narratives observed on social-media platforms. The database helps Microsoft and other websites to stop the spread of harmful information.

In an op-ed for The Lancet, psychology professor Eldar Shafir describes eight well-established human tendencies that could undermine one’s ability to make sound judgments during a time of crisis such as the pandemic. In the piece, titled “Pitfalls of Judgment During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Shafir and co-author Donald Redelmeier, senior scientist at the Sunnybrook Research Institute, describe how notions such as fear of the unknown and an instinct to adhere to the status quo should be considered by officials formulating public-health messaging.

The flu epidemic a century ago waned during the summer months, only to come raging back in winter, but the COVID-19 pandemic will probably not mimic that pattern during its wave of infection this summer. According to research by Princeton Environmental Institute postdoctoral researcher Rachel Baker, published in the journal Science in May, the SARS-CoV-2 virus will likely not be hampered by warmer weather until after the virus becomes endemic throughout the world’s population. By running simulations using information from similar coronaviruses, Baker and her co-authors concluded that during the pandemic stage, warm weather probably will have only a modest impact on infection rates.

No responses yet