As the first World War overtook Europe, America — and Princeton — looked on. This timeline, drawn from PAW columns, documents events preceding, during, and after the United States’ entry into the war.

Oct. 11, 1916

A new academic year brings new faces — freshmen in the Class of 1920 and faculty, including Capt. Stuart Heintzelman of the 6th Cavalry, U.S. Army. Heintzelman is brought on as “professor of military science and tactics,” teaching an elective course for juniors and seniors entitled “Military History, Policy, and Minor Tactics.” PAW reports that the course will supplement practical military training conducted at camps such as the one in Plattsburgh, N.Y.

Nov. 15, 1916

Jan. 31, 1917

With the likelihood of the United States entering the war growing, a poll shows 86 percent of students in favor of “universal military training.” Dean of the College Howard McClenahan expresses his support for the proposal, saying that “whether looked at from the point of view of the military needs of the country or of the moral standards of the country, universal training would, in my opinion, be invaluable.”

Feb. 3, 1917

America breaks diplomatic relations with Germany, making war all but a certainty. PAW publishes passionate writing about the University’s potential role in the conflict: “If war it must be, if the college men of America in common with their fellow citizens are called upon to fight, foremost among them will be found the men of Princeton, upholding alike the honor of their country and the honor of their Alma Mater, and giving a new significance to the historic slogan, ‘Princeton in the Nation’s Service.’”

Preparations begin immediately at Princeton, with a Princeton Provisional Battalion organized for the training of military officers. More than 500 students sign up to join on the first day. Capt. Heintzelman strongly supports the measures. “Princeton men — all college men in fact — should be trained to be officers,” he says.

Feb. 14, 1917

Almost 900 students — 60 percent of the undergraduate population — have now enrolled in the Princeton Provisional Battalion. A committee comprised of President John Grier Hibben 1882 *1893 and alumni is appointed to investigate “the feasibility of having a government aviation camp established at Princeton.”

March 21, 1917

PAW reports that three war-preparation measures have been unanimously approved by the faculty. One asks for government certification of the Provisional Battalion as a unit of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, another instructs Princeton scientists and laboratories to be “turned over to the service of national defense in case of war,” and the third implements a military census of all alumni and faculty to assess those willing and able to serve the United States.

April 4, 1917

With an “extraordinary session” of Congress assembling later in the week to, presumably, declare war, PAW features a full-page letter sent from President Hibben to the parents of all students. In it, he assures that in the case of war “there is no intention of closing the University,” and that “work will continue very much as usual though certain adjustments in the curriculum will be made to enable certain students under military training to qualify as officers.” He also promises that the University will “take the appropriate action necessary to prevent any injustice in the matter of credit for university work and the granting of degrees in the case of students called into the nation’s service and compelled to leave the University before the end of the academic year,” while urging students and parents to not make hasty decisions to enlist.

April 11, 1917

War is declared against the German Empire on April 6, and a flurry of activity greets the now-wartime University. Alumni are invited to return to campus to undertake Reserve Officers’ Corps training. Provisions are codified ensuring students who leave before the end of the semester for military service will have their classes credited as completed. Furthermore, underclassmen are permitted to drop one of their five classes and replace it with a military studies class for credit.

Letters in PAW reflect diverse sentiments about the war. David Potter 1896 invites readers to secure commissions in the Pay Corps of the Navy, which he reports pays “nearly $2,000 a year.” Cedric Lewis 1915 writes in opposition to the “universal military service” endorsed by the University. Samuel Huston 1892 reminds alumni that “college men” should prepare for war not just by drilling, but by using their “genius” to ultimately pursue peace among nations.

April 25, 1917

A section entitled “Military Affairs at Princeton,” penned by Donald Grant Herring 1907, appears in the pages of PAW, where it will run until February 1919. The inaugural column reports on additional training for current R.O.T.C. participants to be conducted at government posts for a period of three months. Also reprinted is a letter to The Daily Princetonian from Assistant Secretary to the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt answering several questions about student prospects in the Naval Coast Defense Reserve. Twenty-five years later, FDR will again be seeking to reassure a nation at war.

May 2, 1917

Unused land on campus and around town has been plowed for wartime farming. War preparations are getting off the ground in more ways than one: The aviation training section has made its first flights at the newly constructed airfield, under the direction of Lt. Edward Kenneson.

May 9, 1917

Many seniors leave campus before Commencement, with more expected to depart. They will need to seek furloughs if they hope to receive their diplomas in person. In an article titled “What is my Patriotic Duty,” Capt. Victor Morrison 1905 urges more Princeton men to offer their services.

On campus, students enrolled in the course “Statistical Methods” are put to work assisting in food production canvassing in nearby towns due to a shortage of farm workers.

May 16, 1917

President Hibben announces that Princeton will resume regular study in the fall semester, with the need for immediate preparation for service having dissipated. Military training will continue to be provided, but will no longer be accepted as equivalent to all or part of a student’s academic work. Authorities at the school hope to keep the campus open over the summer for military training.

Thirty-one faculty members have left to enter government service. Faculty whose terms are ending this year will not be reappointed, as the University works to reduce expenses. Quadrangle and Colonial Clubs close due to a loss of members, and Charter is expected to close soon. The remaining clubs have about a dozen members each and plan to remain open.

May 23, 1917

The ambassadors and ministers representing the Allied Nations at Washington, the Secretary of State, and the Chairman of the American Commission for Relief in Belgium accept invitations to Princeton’s Commencement, where they will receive honorary degrees.

Professor Theodore Hunt 1865 writes about attending Princeton during the Civil War. He recalls the affectionate farewell of undergraduates leaving to fight on opposing sides, and the generous spirit that existed between the students from the North and South who remained on campus. Unlike in the current war, Hunt notes the unaffected nature of college exercises during his undergraduate years, but states that then, like now, the country was engaged in a struggle on behalf of human freedom and the rights of man.

May 30, 1917

One of seven aeronautical schools at educational institutions is to be established at Princeton. The school will enroll around 200 hundred students at a time to receive preliminary training for federal aviation camps. This is expected to ease some of the University’s financial burden, but PAW reports that the school still expects extreme difficulty in meeting expenses during the war.

June 6, 1917

President Woodrow Wilson 1879 writes a letter expressing his regret at being unable to attend Commencement. The administration sends an appeal to alumni for donations and explains the University’s serious financial situation.

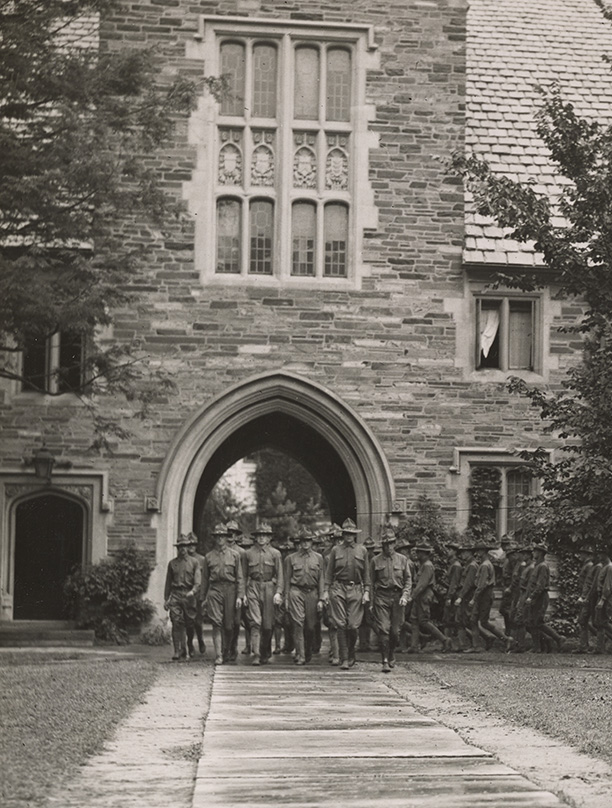

Oct. 3, 1917

As Princeton reopens, a preliminary survey shows that the University will have approximately 57 percent of the previous year’s registration, with the heaviest losses among upperclassmen and the Graduate School. The decrease is largely made up by enrollment in the aeronautical school, with the dormitories Brown, Cuyler, and Patton reserved for the exclusive use of the aviators. Seventy faculty members have now responded to calls for service, including a number who have enrolled in the Army or Navy. Princeton will not have a varsity football team this fall.

Over the summer, eight Princeton men were awarded decorations for war service for providing ambulance service during the heavy fighting on the Western Front. The President also announced that nine Princeton men have now lost their lives in war service. The “honor roll” of deaths begins making frequent appearances in Herring’s column, now titled “Princeton in the Great War.”

Oct. 10 and 24, 1917

Another ambulance-service volunteer, Horace Franklin Simon 1917, shares his experiences in a letter from “somewhere in France,” dated Aug. 1. In it, he describes tending to soldiers wounded by shelling and gas attacks, maneuvering over smashed roadways, and attending the funeral of soldiers “laid to rest in the soil of France, the heavy boom of the cannon, pounding on the lines of the enemy, furnishing the music to the priest’s final blessing.”

Nov. 7, 1917

The University’s Committee on War Records reports that at least 1,900 Princeton men are in service. A 10th alumnus has died in war service — John Reynders Jr. 1917, who was thrown from his airplane during a training exercise in Long Island.

Nov. 21, 1917

Former President Theodore Roosevelt delivers the annual Stafford Little Lecture, speaking on the topic of “National Strength and International Duty.” After the address, he visits Poe Field to review cadets in the aeronautical school.On campus, wartime rationing has meant changes in the dining halls, where there are two “meatless” days each week and new limitations on sugar — one lump per person, and only for coffee (none on breakfast cereal).

Meanwhile, in France, John Carroll Jr. 1912 receives a surprise visit from an old friend, Cyrus Chamberlain 1910, a member of the Lafayette Flying Corps who spied an American flag on Carroll’s tent and made an unscheduled landing to ask for a loaf of bread. According to a story relayed by Carroll’s father, Chamberlain saw his fellow Princetonian and exclaimed, “Hello, Johnny, what the deuce are you doing here?”

Nov. 28, 1917

Henry Buxton 1894 shares a letter from aboard the USS Harvard, on patrol in European waters: “Between rescuing ships that wireless us ‘am being chased by subs,’ having ships ‘torped’ while under way, picking up a shipwrecked crew, and meeting and bringing in our own transports, we will not suffer from ennui.”

Dec. 12 and 19, 1917; Jan. 9, 1918

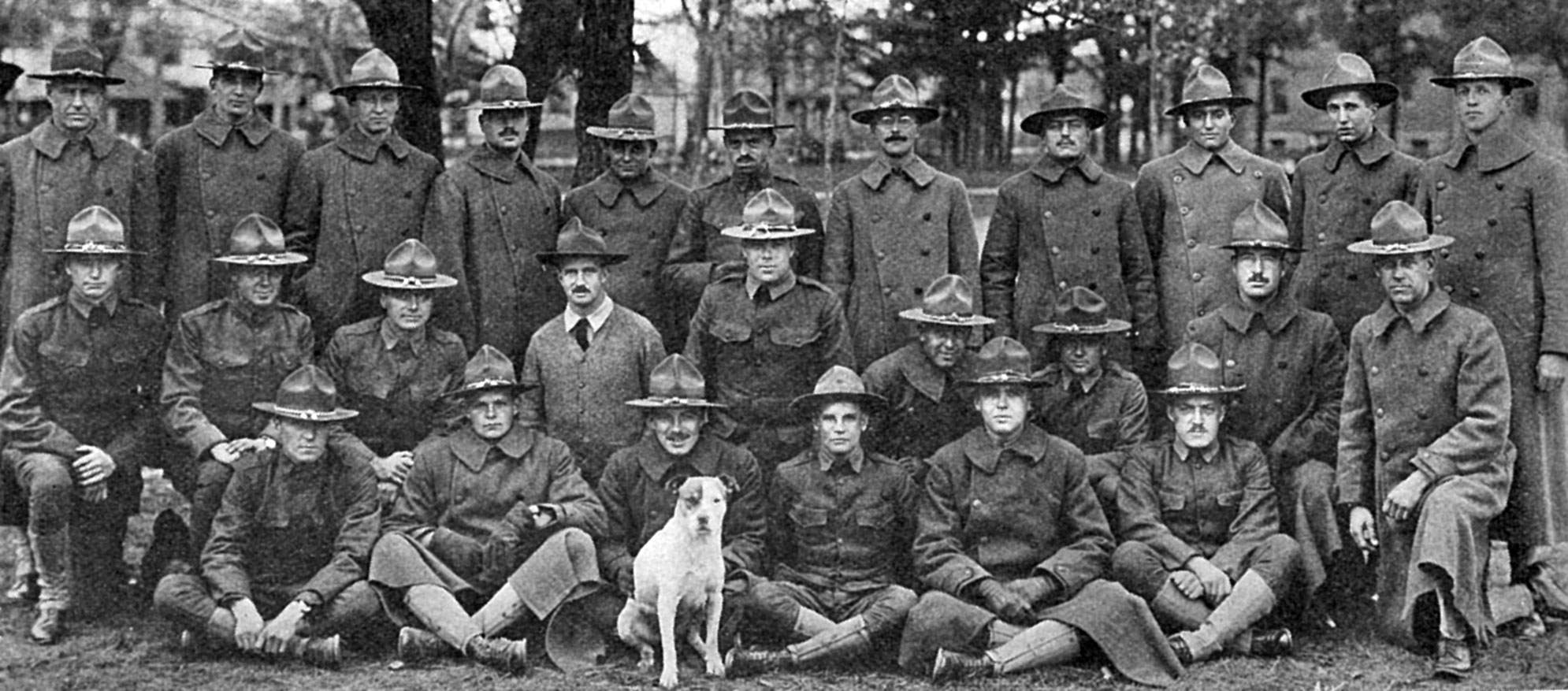

Three consecutive issues of PAW report on the deaths of Princetonians: Donald Ross 1917, who died of wounds received in action; Eric Anderson Fowler 1919, who was killed at an aviation school in Francel; Benjamin Stuart Walcott 1917, an aviator shot down behind enemy lines; Walter Foulke 1905, who died of pneumonia while training in Texas; Franklin Perry 1911, who died of meningitis while in training; James Dana Paull 1917, who was killed in an airplane accident; and D.N. Campbell Ross ’17, who suffered a head wound in Belgium.

Princeton men continue to depart for the war, including the Officer Training graduates pictured here.

Jan. 16, 1918

Neilson Poe 1897, a lieutenant of the American Expeditionary Force in France, has won the 145-pound class in an officer’s boxing tournament. And former Tiger football and hockey star Hobey Baker 1914, now a lieutenant in the American Flying Corps, inspires a poem by Philadelphia Evening Ledger columnist Tom Daly that notes the onetime “champion at hockey” now serves “as a wild, aerial jockey.”

Feb. 13, 1918

Based on the space allotted, letters from Princeton’s aviators are among the most treasured items printed in PAW. The magazine publishes three installments of the late Benjamin Stuart Walcott 1917’s dispatches from France. On Nov. 30, 1917, two weeks before his death, Walcott balked at his father’s idea of taking a safer job, away from the front. “I had rather get a Boche than any commission in the Army, but one cannot always tell about the future,” he wrote. “Perhaps after a few good scares, I’ll be ready to jump at a monitor’s job.”

Feb. 20, 1918

Rev. Kenneth Miller 1908, who was serving with the YMCA in Russia during the revolutionary days of the previous fall, writes about that country’s outlook: “It is hard sometimes to be patient with the Russians when one thinks of the cause they are endangering, but we have to be sympathetic and help them solve their own problems in their own way.”

March 27, 1918

Paul D. Nelson 1917’s letters home from aviation school in Foggia, Italy, describe a reunion dinner of 14 Princetonians, followed by the singing of college songs. Other alumni check in from around the globe. Rev. S.V.R. Trowbridge 1902 is serving with the YMCA in Jerusalem. Leys A. France 1919 is in France with an American artillery unit. And Philip A. Moore 1902, who enlisted in the Canadian Army in 1914 and served in France, has returned to Alberta to train soldiers.

April 24, 1918

PAW provides a full roster of the 3,322 students and alumni serving in the military or in war-related volunteer roles. Nearly half are in the Army, followed by the Navy and the Army Air Service. Their class years range from 1921 to 1862. The list of names stretches over 19 pages.

May 8, 1918

Neilson Poe 1897 describes embarking for the trenches of the Toul sector of France: “We were told to store away our surplus stuff, hold fast to a hundred rounds of iron rations, brighten up the bayonet, and be ready to steal away in the early hours of a cold, frosty morning. How like starting off for a Yale-Princeton game!”

At the front, he writes, “you always keep your clothes on, including boots, and if you average four hours’ sleep a day, you are lucky. … A sentry looking into ‘No Man’s Land’ can see many more things that are not there than are there… . The longer he looks the surer he is that there is someone in the wire. The posts take human shape and begin to move.”

May 29, 1918

“The Captain had just crawled away when a German shell struck the disabled machine and blew it to tinder.”

Biddle took shelter in the holes created by the German shells, and troops from the Allied lines retrieved him safely.

June 12, 1918

The University’s Committee on War Records reports 3,583 Princeton men in service on the eve of Commencement for the Class of 1918. Only 52 of the original 394 members of the class will be on campus to collect their degrees in person. War records for the Graduate College have not yet been finalized, but a preliminary note reports that at least 92 of the 105 students in residence at the Graduate College in 1916-17 are now in service, along with roughly 80 percent of the students from 1917-18.

Military training continues to reshape the campus: Near Palmer stadium, students led by a visiting French lieutenant have been building trenches in order to learn “modern warfare.”

Oct. 2, 1918

As the University begins its 172nd year, PAW reports on the latest from Europe, where 18 alumni and students have been killed in action, 16 of them in France. Others are convalescing after suffering wounds in battle. Donald O. Page 1917, a Marine, writes home following a mustard-gas attack. “I seem to be lucky as my eyes are all right again, after being blind for a day or two,” he writes. “The effect of the gas on my lungs is the only thing holding me in bed.”

While the summer’s news is grim, the war seems to be nearing an end. On Oct. 4, the Germany chancellor telegraphs President Wilson to seek an armistice with the Allies, the first step in more than a month of peace negotiations.

Nov. 20, 1918

News of the Nov. 11, 1918, armistice was met with joyous celebration in Princeton, where students in military dress marked the occasion with an impromptu parade on Nassau Street. But in PAW, the happy news was accompanied by somber reports of seven alumni deaths in the final days of the conflict. Additional deaths would continue to be shared through February, when the final “Princeton in the Great War” column reported that 127 Princeton men had “given their lives in the service.” (According to more-recent research by the University Archives staff, 117 students or alumni were killed, along with three faculty members.)

In December, a famous Princeton name would be added to the heartbreaking honor roll when Hobey Baker 1914 crashed during a test flight in France. His epitaph, penned by his cousin, poet Mary Amory Hare, captures the tragic losses of a conflict that killed millions in less than five years:

You who seemed wingéd, even when a lad,

With that swift look of those who know the sky,

It was no blundering Fate who stooped and bade

You break your wings and fall to earth and die.

I think one day you may have flown too high,

So that Immortals saw you and were glad,

Watching the beauty of your spirit’s flame,

Until they loved and called you and you came.

No responses yet