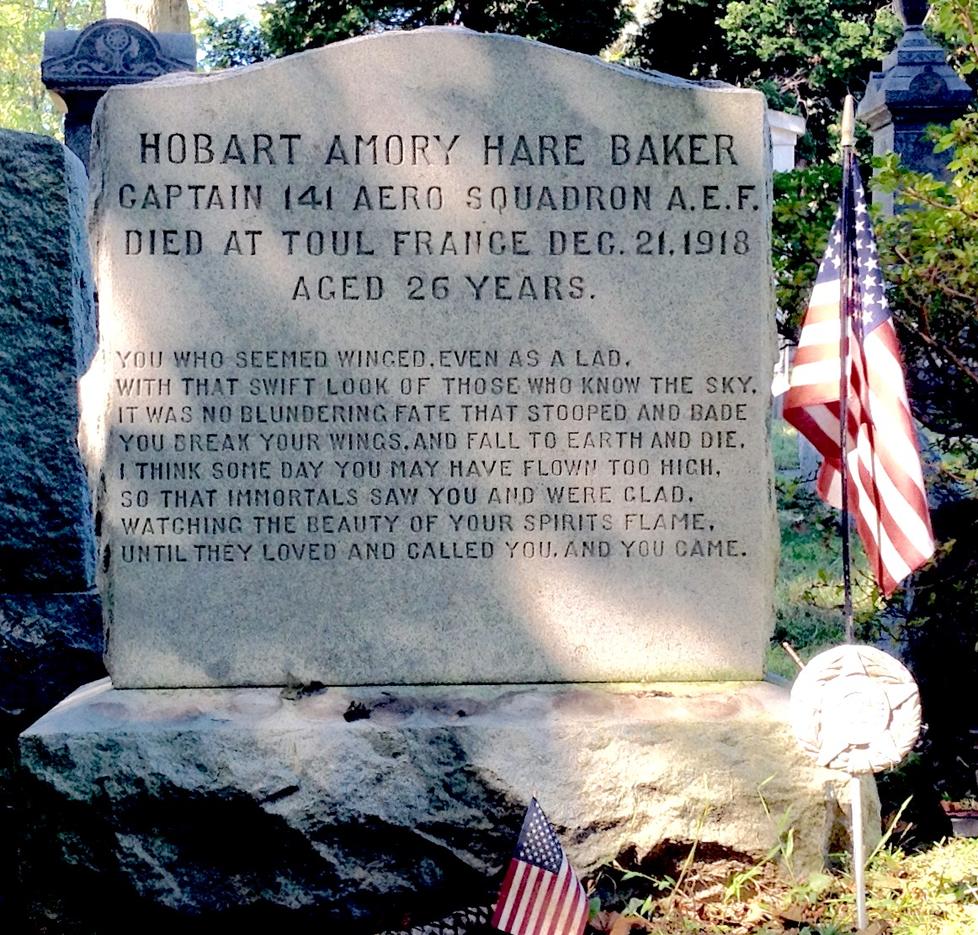

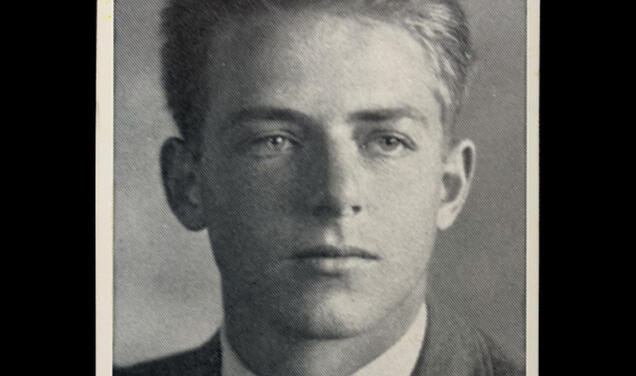

For anyone who has read or heard about Hobey Baker 1914 — the renowned sportsman and World War I flyer who died at 26 when he insisted on making “one last flight” shortly after the armistice — these eight lines of verse may ring a familiar bell:

You who seemed wingéd, even when a lad,

With that swift look of those who know the sky,

It was no blundering Fate who stooped and bade

You break your wings and fall to earth and die.

I think one day you may have flown too high,

So that Immortals saw you and were glad,

Watching the beauty of your spirit’s flame,

Until they loved and called you and you came.

That is, of course, the famous poem inscribed on Baker’s tombstone, a lofty lamentation that seems to capture (and perhaps played a part in creating) the almost impossibly heroic, romantic, tragic, mythical tale of his life and death.

Davies, who served as PAW’s editor-in-chief from 1955 to 1969, left to Princeton the rich cache of historical documents on which he had based his book. (They are now housed at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library.) Within one of those documents is an intriguing reference to the epitaph, which in late 2014 led me, after some modest detective work, to the author’s identity — and to an ironic twist involving PAW. It is unclear whether Davies simply failed to follow the clue or did follow it and then deliberately chose not to acknowledge the poem’s creator. Ditto for subsequent biographers, who have had access to the Davies collection for 50 years.

The verse on the stone is the work of Mary Amory Hare, who was born in Philadelphia in 1885 and died in Santa Barbara in 1964. Although largely unknown now, she was an accomplished writer, widely recognized during her lifetime. Harper’s Magazine featured one of her poems as early as 1913. By the mid-1920s, Harper’s, The Atlantic Monthly and Scribner’s Magazine had carried much more of her poetry and fiction. She published her first book, a collection titled Tossed Coins, in 1920 and followed it with The Swept Hearth in 1922, The Olympians in 1925, Sonnets in 1927, Deep Country in 1933, and Between Wars in 1955. Two of her short stories were adapted into plays and produced on live television in the 1950s. She gained distinction, too, as a skilled painter and equestrian. (“Amory Hare” was her usual nom de plume; but her work sometimes appears under the surnames of her first and second husbands, Arthur Bryant Cook, an admiral, and James Hutchinson, a physician who had been a fine rower and football player at Harvard.)

Hare was more than a distant admirer of the widely celebrated Baker. She was his cousin, the daughter of one of his mother’s sisters. Until Hobey entered St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire at age 11, both he and Hare lived in the Philadelphia area; and, according to newspapers of the day, their families socialized together. Being seven years older, she would not have known him as a playmate or contemporary, but rather as a baby, a younger child and a younger adult. She likely glimpsed the early manifestations of his spellbinding athletic skills and charismatic personality.

It was quite soon after Hobey died in December 1918 that Hare composed the poem destined to become his eulogy in granite. That is certain because – and here is the irony – she published it, signed, on April 9, 1919, in this magazine. She then included it in Tossed Coins the following year. (Oddly, the PAW card catologue at Mudd Library appears to contain no entry for the poem.) The lines were most likely engraved on the headstone in the spring of 1922, just before the stone was placed at the gravesite. Thence began their curious journey to fame as Hobey Baker’s “anonymous” epitaph.

Note: The original PAW version of the poem is reproduced above. The Tossed Coins version is virtually identical, but the tombstone version reflects a few significant changes that are probably corruptions over which Hare had no control.

1 Response

Tim Rappleye

7 Years AgoJ.P. — Well done sir. Please...

J.P. — Well done sir. Please email ASAP