Walter Kirn ’83 lives in a converted bunkhouse on a side street in Livingston, Montana.

The bedrooms and living room occupy the entire second floor, but owing to the way the house is organized, the kitchen, as well as a bathroom and his office are on the first floor, in what was once an old storefront, and are inaccessible from the rest of the house. Whenever he or his wife want to get something from the refrigerator or a book from Kirn’s desk — in rain, snow, freezing cold, or dead of night — they must go outside, walk a few feet down the sidewalk to their “other” front door, then reverse the steps going back.

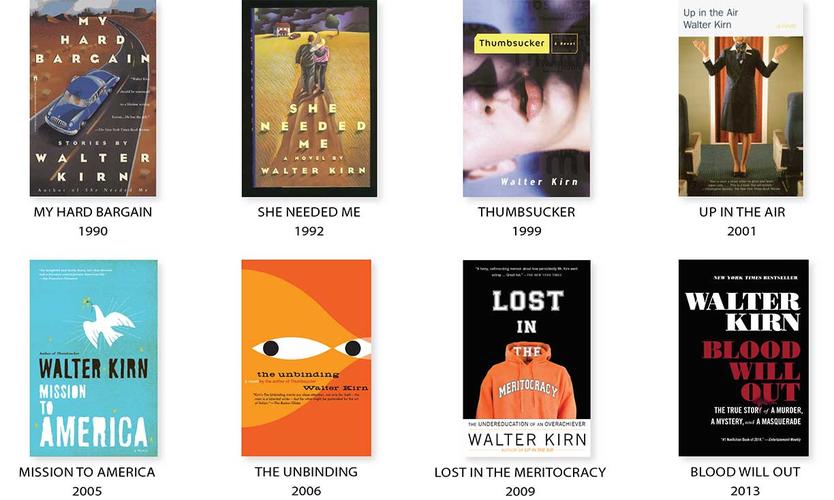

Surely, there’s a metaphor in here somewhere. Let’s start with a project that Kirn, a prolific columnist and the author of eight books, is now finishing, one that has been percolating in his brain throughout the pandemic. Called The Last Road Trip, it details a 2½-month journey he made across the country in 2018. It is scheduled to be published by Liveright, an imprint of W.W. Norton, at a date to be determined once he completes the manuscript.

Four years and counting is a long time for him to work on a book, Kirn admits. COVID had a lot to do with that, but the “investigative travelogue” is a new genre for him and has taken some getting used to. He was also sidetracked caring for his father, Walter Kirn ’60, who died of ALS in 2020.

“For me, the real tension in the country is between the people who feel condescended to and the people who feel unjustly accused of condescending to them.”

The road trip in search of America has been done, of course, by Alexis de Tocqueville, John Steinbeck, and many others, but Kirn was unafraid to insert himself into such company. In the same spirit as some of his literary predecessors, he wanted to learn if the country really looked like the picture that was being fed to him on cable TV and social media. He wanted to see, in other words, “if there was anything to be surprised by.”

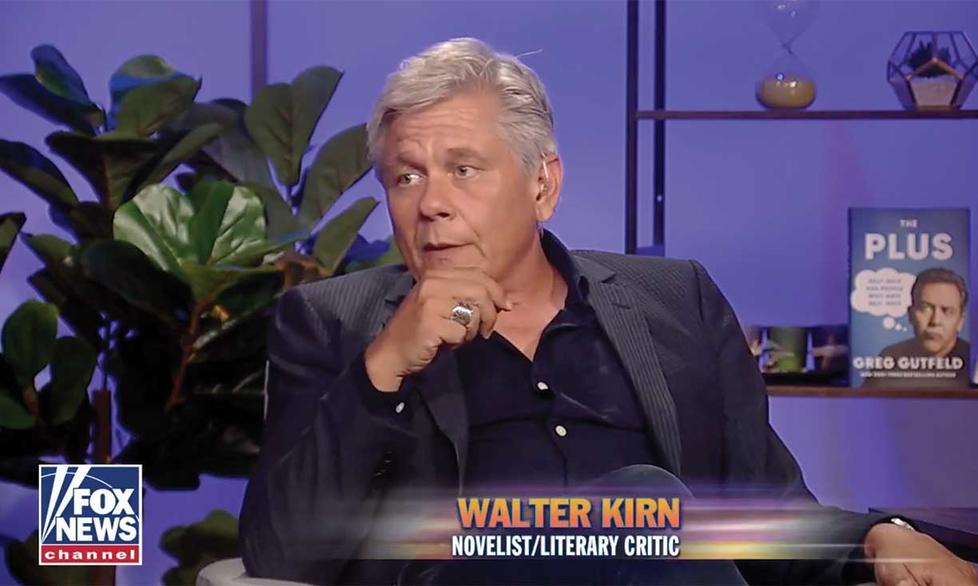

These are not new concerns for a writer who has mined overlooked corners of American life throughout his career. Recently, he has even been touted as a champion of “flyover country” (a term coined by his ex-father-in-law, writer Thomas McGuane) and become a regular on Greg Gutfeld’s late-night talk show. You and your friends might not watch Gutfeld, which airs on Fox, but he routinely outdraws Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Kimmel, and Bill Maher. Ever the outsider, ever the insider, Kirn perceives that there are many things we no longer know about each other. In his view, much of modern America — the seemingly unbridgeable divide between left and right, blue states and red states, and perhaps even between elite universities such as Princeton and the rest of the country — might be likened to a house in which the rooms no longer connect to each other, separated by a wall, with no door between them.

Is that too glib? If it is, Kirn seems up for the discussion. “No one,” he laughs, “intellectualizes more than a literary critic on a road trip.”

Four years after he returned from the road, Kirn recounts his journey while comfortably seated in his first-floor study, his desk strewn with papers including another of his recent projects, an introduction to his friend Quentin Tarantino’s novelized version of the film Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Two of Kirn’s own novels, in fact, Thumbsucker and Up in the Air, have been made into movies. He moves comfortably in celebrity circles, with another residence in Las Vegas and a family ranch in the hills above Livingston where Michael Keaton and Tom Brokaw are neighbors.

Despite the comforts of home, Kirn enjoys the road, so much that when he worked in Los Angeles, he would often drive there from Montana, nearly 2,400 miles roundtrip. Though it would not be called a travel book, the most personal of Kirn’s journeys was the one he wrote about in Lost in the Meritocracy (published in 2009), which concerned his spiritual and intellectual trip from rural Minnesota to Princeton. On one level, it is a scathing sendup of Kirn’s attempt to master the rat’s maze of standardized tests that got him into the University and opened a future of wealth and accomplishment. “I was the system’s pure product,” he wrote, “sly and flexible, not so much educated as wised up.”

But the book is also a story of the tension between belonging and standing apart. Though he fit in chameleonlike with his striving classmates, Kirn managed to critique the meritocracy as well as join it. He arrived on campus after spending his freshman year at Macalester College but, unusual for a transfer student, was also a Princeton legacy. Kirn’s father, a patent lawyer for 3M, converted the family to Mormonism in the early 1970s and moved them to the tiny town of Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota, where Kirn grew up. (Kirn has since left the church.) The switches, Kirn wrote of his father, were “just one more phase in his campaign against convention and conformity.” In that respect, at least, the apple did not fall far from the tree.

As a Princeton undergraduate, Kirn relied on “[f]lexibility, irony, self-consciousness, [and] contrarianism” to survive. He fought with his snooty roommates, joined “bitterly nonconformist” Terrace Club, and majored in English, submitting a 22-page collection of poems as his senior thesis. (“It’s rather thin, isn’t it?” he recalls his adviser, Joyce Carol Oates, remarking when he turned it in.) For all the tension and angst he experienced, the University served Kirn well. “A diploma ... was the least of what Princeton had to offer,” he wrote in one trenchant passage; “The major payoff was front-row seats. To everything.”

Was it ever. Former Provost Neil Rudenstine ’56 noticed Kirn and got him an interview for a Keasbey Scholarship and a spot at Oxford. Returning to New York after two years in England, Kirn toyed with the idea of becoming a playwright before publishing his first book, a collection of short stories, in 1990. Since then, he has moved between fiction and nonfiction, while also writing for some of the country’s most prestigious periodicals, including The Atlantic, New York Magazine, GQ, Esquire, Time, and Harper’s. He has taught nonfiction writing at the University of Chicago.

Kirn’s career is remarkable, not only for his ability to move between genres, but for his incisive descriptions, vast literary references, and acid humor, the latter of which he is willing to turn on himself. The Cleveland Plain Dealer, in a review of his 2006 novel, Mission to America, called him “one of the nation’s best satirists.” Someone with such gold-plated credentials might be expected to know his own country. But sensing that something was missing, with the political fires roaring and the pandemic still unimagined, Kirn got into his Jeep Cherokee one morning in February 2018 and took to the road.

Traveling cheaply and subsisting on snack food and soda, Kirn adjusted his path as the mood struck him. After setting off from Las Vegas, he crossed the country’s southern tier, spending long stretches in New Mexico and Mississippi, cutting across Tennessee coal country, and finally reaching the North Carolina coast before returning by way of southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Unlike some literary road trippers, Kirn neither stuck to the interstates nor avoided them. “The trip,” he insists, “was not about nostalgia or romanticism.”

Rather than dwell in the big cities, though, Kirn explored Indian reservations, military bases, and hollowed out small towns. There he found a country that was more durable than he had been led to believe but also deeply bruised — by deindustrialization, globalization, the opioid epidemic, a brain drain, and nearly two decades of war. Outside the enclaves of prosperity and education, Kirn learned, American life is pretty tough.

Moreover, many of the people he knows, works with, and went to school with don’t help. Kirn unloaded on them in a long interview with The Wall Street Journal last November that proclaimed him “Middle America’s Defiant Defender.” It may seem an odd title to bestow on someone with Kirn’s credentials, but he still considers himself a small-town boy and embraces much of their pride and resentment as his own. “I see the American establishment playing the part of bully toward its own people,” Kirn told the Journal, decrying the banks, law firms, think tanks, and tech companies that “extract wealth [and] energy ... from the provinces and then give back contempt as their end of the deal.”

“It’s kind of wonderful to me that Princeton isn’t perfect. Because it sure looks like it is. And it sure acts like it is a lot of the time. It should delve deeper into itself, but I don’t think it should act embarrassed of itself.”

He has harsh words for the Democrats who, he believes, cloak their empathy with condescension. It is a point that several political scientists have made in less pointed terms and is at least partly borne out by the party’s ongoing struggle to win support from those without a college degree. For those voters, as Kirn sees it, the problem is that many progressive policies “are not couched in language they understand, and too often they’re couched in language that offends them. It’s hard to tell a coal miner who watched his father cough his lungs out that he has privilege.”

If those voters have a chip on their shoulder, Kirn seems to have one, too. “One thing I really noticed about Americans — they don’t like being talked down to, no matter who they are,” he says. “For me, the real tension in the country is between the people who feel condescended to and the people who feel unjustly accused of condescending to them.”

Unfamiliarity and ignorance run both ways, though. Kirn says he encountered many people in rural America who were convinced, from all they had seen on television and social media, that big cities are war zones of crime and homelessness. He was even more startled to discover how little people knew about their own neighborhoods. To promote conversation while on the road, Kirn made it a point to ask for directions rather than rely on his phone. Often, people couldn’t direct him to places just a few dozen miles from where they lived, and they sometimes resented being asked.

“You walk into a bar in the old Westerns, and everybody looks up and gives you a once over,” he says, recounting the experience. “You walk into a bar nowadays and no one looks up.”

The pernicious effect of technology, particularly our addiction to our phones, is a theme of much of his recent work, though Kirn himself, an avid tweeter, blogger, and podcast guest, is hardly a technophobe. Still, he is skeptical that surrendering our photos, biometrics, daily movements, and news gathering to the metaverse will be a fair trade. In a similar spirit, Kirn has turned against what he considers the controlling, rule-laden censoriousness that he sees everywhere around him, which is couched in the language of fairness, safety, and tolerance yet often brooks no dissent.

He delineated his complaints most emphatically in a Substack post last July titled, “The Bullshit.” “Comfort yourself with thoughts that the same fortunes engaged in the building of amusement parks, the production and distribution of TV comedies, and the provision of computing services to the defense and intelligence establishments have allied to protect your family’s health, advance the causes of equity and justice, and safeguard our institutions,” he wrote. “Dismiss as cynical the notion that you, the reader, are not their client, but their product. Your data for their bullshit, that’s the deal.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Kirn has burned several bridges with old friends in the media establishment. His former employer, The Atlantic, he says, “manages to outrage me on a regular basis nowadays,” and he has suggested that Harper’s declined to renew his contract after he wrote a column that skewered the left as “scolds and dullards.” (The magazine’s publisher has said that Kirn was let go because he was late turning in his columns.)

All this may also give some perspective to Kirn’s participation on Gutfeld’s show, which he flies to New York to do in person about once a month. Gutfeld!, as it is now called, is late-night television for the red states, and it has quickly soared to No. 1 in the ratings, including among viewers ages 25 to 54. Kirn says he does the show because he and Gutfeld are longtime friends and likens its panel discussions to “tossing a ball around the infield,” though on Gutfeld’s previous talk show, “The One,” at least, his fellow infielders included Eric Trump and the ball consisted of jokes about Georgia’s new restrictive voting law.

Journalist Matt Taibbi, who has been doing a current events and culture podcast with Kirn, suggests that Gutfeld! fills the same role for conservatives that The Daily Show filled for progressives during the George W. Bush years. Kirn does the show, Taibbi proposes, because CNN, MSNBC, and other outlets no longer tolerate his brand of heterodoxy. “They’re not welcoming to somebody who might have an ironic take on the news,” he adds. “They’re not invited that into the airspace of mainstream news consumers, so they go on Fox, because that’s where audiences are.”

Donald Trump was once a target of Kirn’s derision, back in the 1990s when Kirn edited the satirical Spy magazine and Trump was just a narcissistic real estate mogul. Today, although Kirn declines to divulge whom he voted for, he says that Trump’s 2016 victory did not surprise him and that he never took allegations of Russian collusion seriously. While prefacing by saying that there was much he did not approve of, Kirn summarizes the Trump years as “a daily battle between an establishment that was horrified and offended and a guy who felt he wasn’t getting his chance to be president.” When pressed about whether the Jan. 6 insurrection changed this assessment, Kirn retreats. “Ultimately,” he says, “I don’t feel that I’m in the business of moralizing about the American story. I’m in the business of understanding it.”

Asked to characterize himself politically, Kirn settles on “anti-ideologue,” but “contrarian” seems just as good a fit. If nothing else, Kirn is someone who feels compelled to step outside whenever he gets too comfortable inside. He thinks it would be healthy if others did, too. “I am an America lover,” he insists, “not in the sense that I want to go out and sing our national songs on the street. But we are a much more complicated, intermingled, eccentric, surprising, and mixed-up country than we appreciate.”

Although Kirn’s road trip didn’t reach New Jersey, odysseys often lead the voyager back home again, and in many ways, Kirn’s spiritual home is his alma mater. “No one,” he acknowledges, “has a more complex relationship to Princeton than me.”

Though his public critique of the University has run to book length, it may come as a surprise to learn that, for many years, the author of Lost in the Meritocracy did interviews for the Alumni Schools Committee. And that he hails Wendy Kopp ’89’s Teach for America, that capstone on the resumes of many meritocrats, as an example of the University’s best service to the nation. Kirn wants Princeton to do more to draw students from overlooked places like the central valley of California, rural Montana, or small-town Minnesota, diversifying itself with a broader set of cultural references and values.

The University has never been representative of the country and need not try to be, Kirn says, but it is at its best when it turns outward, applying its tremendous resources to addressing pressing national problems. It is less than at its best when its gaze turns inward. Kirn does not begrudge the University’s recent attempts to correct its history of racism, sexism, and antisemitism, but fears that they often devolve into what he characterizes as “endlessly repetitive mea culpas” that are both self-serving and fruitless. “I just don’t know that self-flagellation ever got anybody to heaven,” he says.

Listen to Kirn talk about Princeton and he begins to sound like Faulkner wrestling with Mississippi, but what he says about the University might apply to the country, too. “Princeton can do whatever it wants to sanitize, renounce, revise, or rebuke its past, but it can’t get rid of it,” he insists. “Just like our body replaces every cell yet still looks like us, Princeton may replace every cell, but it will still be Princeton. Its attempt to elude that truth seems a little doomed. For all its sins, it has no other identity to jump to.”

No one intellectualizes more than a literary critic on a road trip, as we have been warned. Still, the road is long and there is so much that is unfamiliar.

“It’s kind of wonderful to me that Princeton isn’t perfect,” Kirn suggests. “Because it sure looks like it is. And it sure acts like it is a lot of the time. It should delve deeper into itself, but I don’t think it should act embarrassed of itself. Because in some ways, the institution that is capable of self-consciousness and improvement and regret is the same one.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

18 Responses

Vicki Spachner

1 Year AgoMy View of Democracy

I only just saw Kirn on Gutfeld and really hadn’t known of him before. I read constantly, follow the news but just can’t keep up with everybody. I share his same philosophy in a way; I am from the deep Midwest (which means Ohio farmlands) and yet was born in Chicago, have lived in Los Angeles’ finest suburbs, Arlington, Virginia, working in lobbying in D.C., mothering in eastern Ohio, Appalachian foothills, writing for newspapers through the years, paying attention to the hypocrisy and the BS that lives in this country. But ultimately we are a nation of differences trying to survive as a genuine democracy that we learned in civics in the 1950s. I work at keeping up with all points of view and then ponder, what in the world causes them to think such radical thoughts?

John Hellegers ’62

2 Years AgoPolitical Orientation and Brain Structure

The URL, below, is for a statement in 2010 from University College London (“UCL”) on the finding by UCL scientists (borne out, before and since, in other experiments) that political orientation on either side of the present political and cultural chasm can actually be detected in the physical structure of the brain, using an ordinary MRI:

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2010/dec/left-wing-or-right-wing-its-written-brain

In the UCL experiment the subjects were asked to declare their own political orientation, on a scale that ran from very liberal to very conservative. After that, the subjects were given an MRI scan, whose results corresponded to their prior self-declarations with more than 80% accuracy.

The basic correlations found were (a) between liberalism and a larger anterior cingulate cortex; and (b) between conservatism and a larger right amygdala. As the UCL statement puts it:

“People with liberal views tended to have increased grey matter in the anterior cingulated cortex, a region of the brain linked to decision-making, in particular when conflicting information is being presented. Previous research showed that electrical potentials recorded from this region during a task that involves responding to conflicting information were bigger in people who were more liberal or left wing than people who were more conservative.

“Conservatives, meanwhile, found increased grey matter in the [right] amygdala, an area of the brain associated with processing emotion. This difference is consistent with studies which show that people who consider themselves to be conservative respond to threatening situations with more aggression than do liberals and are more sensitive to threatening facial expressions.”

There’s no shortage of other scholarly material available online about the functions of the amygdala (left and right) and more generally the so-called “reptilian brain” of which it’s a part.

I wonder whether how the “brain drain” of the last 60 years from Red State America to the major cities and university towns affects this. Meritocrats, after all, generally seek out other meritocrats in marriage, and the effect may be, over successive generations, to accentuate still more their characteristic brain structure.

For the highly negative effects of such polarization on those left behind, and therefore on society as a whole, see Michael Young’s prescient book, The Rise of the Meritocracy (1958).

Rick Mott ’73

1 Year Ago21st Century Phrenology

Fascinating to learn that phrenology still exists in the 2st century, albeit in more sophisticated form.

Gar Morse ’69

2 Years AgoDisparate Opinions

I read Mark Bernstein’s piece about writer Walter Kirn with interest and hope to learn about the reasons why we have such disparity of opinions of what our country is all about. Based on that, I resolve to stop all my condescension to people in “flyover” states and just recognize the north end of a deliberately south-bound horse when I see one.

Van Wallach ’80

2 Years Ago‘You and Your Friends Might Not Watch Gutfeld ...’

I had to chuckle at the passage in the profile of Walter Kirn that helpfully explains who Greg Gutfeld is. I couldn’t tell if the phrase that “You and your friends might not watch Gutfeld, which airs on Fox …” was serious or a spoof of the possibly blinkered media views of PAW readers. I guess if late-night host Gutfeld is beyond the pale of acceptable discourse owing to his network and thus unknown to “you and your friends,” then the article needed the details. Still, the article could have phrased the reference in a more straightforward way rather than assume Princetonians don’t watch or even know about the program that dares to outdraw Colbert, Kimmel, and Maher. Mark Bernstein’s article does do a good job later at analyzing why Kirn would go on Gutfeld’s program, as a tolerant outlet that welcomes Kirn’s “brand of heterodoxy.” What a transgressive idea that is.

Rick Mott ’73

1 Year AgoProving Kirn’s Point?

Yes, that phrase leaped out at me as well, coming as it did on the heels of the “people who feel condescended to” break-out quote in the middle of the page. It seemed to imply no right-thinking (perhaps that should be left-thinking?) reader of PAW would ever deign to watch something that “airs on Fox.” Proof by example of Mr. Kirn’s viewpoint, no?

Teddy Zhou ’83

2 Years AgoMaking Room for Heterodox Views

Many thanks for the November article featuring Walter Kirn by Mark Bernstein, two distinguished members of my class. I was especially pleased to see that an established author and critic, perhaps respected by both sides of the political divide, is trying to cross or even bridge this divide.

Other than also being a transfer student, I can hardly find anything in common with Kirn, at Princeton or afterwards. However, reading his story made me feel vindicated for my own “heterodox” views. His criticism that some Democrats cloak their empathy with condescension was sharp. It could be subtle and unintended, but really felt. During the early days of the pandemic, I was asked on several occasions if I had been mistreated for being Chinese. The concern was no doubt well-meaning and may be valid, but it inevitably woke me up to the fact that I was, after all, different.

In my school days in China students whose parents happened to have owned businesses or land, large or small, before 1949, were compelled to search for and confess every bit of influence from the exploiting class, to which their parents belonged. The nightmare worsened during the Cultural Revolution. “Self-flagellation,” or self-criticism in contemporary Chinese vocabulary, was common in those days. It was not for anyone to get to heaven but simply to get out of the living hell, mentally and sometimes physically. I hope we shall never see those days in our country and our university.

Rick Mott ’73

1 Year AgoUnintentional Harms

Your letter struck a chord with me.

I used to run an engineering group for a small scientific instruments company. I also ran the Princeton Go club for nearly 30 years.

In the early ’90s, I received a resume from a Chinese man who had gotten his wife and child out of China three weeks before Tiananmen Square, and couldn’t support them on a grad student stipend. One of his extracurricular items was regional Go champion. He happened to reach out to one of the vanishingly few American hiring managers who would have any understanding of what that meant. Needless to say, we hired him. He would sometimes play in the regional Go tournament held on campus from 1990 to 2016.

Then in 1993, for our 20th reunion, because we were the first class with women our leadership decided we were the “revolutionary” Class of 1973 and dressed us up in Mao jackets and caps, as you doubtless remember. I cringed when I saw my Chinese friend in the crowd with his son watching the P-rade, wondering what he must have thought. And I’m sure he wasn’t the only one seeing it as something other than an amusing costume.

Ramsay Harik ’85

2 Years AgoMoral Blindness

It is astonishing to read that self-professed America-lover Walter Kirn ’83 refuses to pass judgment on the Jan. 6 assault on American democracy. He claims instead that he’s “not in the business of moralizing.” One wonders what it would take for him to awaken to the moral dimension of public life. Another Kristallnacht, perhaps? How about the slaughter of Ukrainian civilians? One also wonders whether he is just saying this for the benefit of his Fox audience. In either case, a character so lacking in moral seriousness hardly deserves such a prominent voice in the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

John Oakes ’83

2 Years AgoKirn as a Political or Social Analyst

The November 2022 article on my classmate Walter Kirn portrays him as a passionate advocate for Middle America. But his vision of Middle America is a particular one. He is self-described (in a New York Times opinion piece, "Why I Dabble in Jeffrey Epstein Conspiracy Theories") as "the next thing to a conspiracy theorist" and claims that pedophile Jeffrey Epstein did not kill himself and may even now be alive. In the Wall Street Journal ("Walter Kirn Is Middle America's Defiant Defender") he sympathizes with Kyle Rittenhouse, who killed two men and wounded another, as "a sort of boy, a little bit out of his depth."

Walter is a first-rate fabulist. To suggest he is a creditable political or social analyst is dubious at best.

Joseph E. Illick ’56

2 Years AgoQuestion Unanswered: Can America Be Understood?

Cheers for Walter Kirn ’83’s long search for America (November issue), especially given the pervasive stress and outright acts against constituted authority that lately have characterized our nation.

Kirn believes “the real tension in the country is between the people who feel condescended to and the people who feel unjustly accused of condescending to them.” (He has no comment on the outright acts.) He hardly enlarges on this extraordinarily inclusive and thus surprising statement, at least not in this multi-page article, but too many exceptions come to mind to regard it as definitive.

He faults Democrats for being speaking a language in their progressive policies that offends those Americans they claim to be concerned with: “It’s hard to tell a coal miner who has watched his father cough his lungs out that he has privilege.” Is this the secret of liberal failure? Kirn informs us that Americans “don’t like being talked down to.”

Kirn also takes aim at the “pernicious effect of technology,” warning you the citizen to remember as your information is gathered: “Your data for their bullshit. That’s the deal.” I suppose Kirn is talking up to his audience here.

According to his biographer, Kirn is very popular on Gutfield!, late night TV for the red states, and although he does not assign Kirn to either political party, he quotes the former Princetonian as describing the Trump years as “a daily battle between an establishment that was horrified and offended and a guy who felt he wasn’t getting his chance to be president.” From the statements of a number of his advisers, I had assumed that theirs were the major, perhaps the only restraints on Trump.

The PAW cover that features a portrait of Walter Kirn asks, “Can America be understood?” The question remains unanswered in this issue.

Norman Ravitch *62

1 Year AgoYes, America Can Be Understood

Understood yes, but also despised. We are about as noble as Mussolini’s Italy.

Steve Beckwith ’64

2 Years AgoBrain Drain

The article on Walter Kirn mentioned the “brain drain” from small and medium cities. I think there is evidence for this every month in PAW. The obituaries from the classes in the 1950s and earlier contain many grads who came from small cities and after graduation returned there. Some were professionals such as doctors or lawyers while others joined a local business, often family owned. They became leaders in the local community. Gradually this changed and many grads from the 1960s and later years shifted to careers in consulting, finance, technology, etc., that were located in large cities. Small cities were the losers in this trend.

In my day, “Princeton in the Nation’s Service” was thought to mean working for the government, especially in Washington, D.C. However, I think that those who returned home to small cities also were working in the nation’s service. An interesting question is whether the country as a whole is helped or hurt by this brain drain.

Geoff Smith ’71

2 Years AgoAnother View of Rural America

Having ridden Harley-Davidson motorcycles more than 300,000 miles, crisscrossing two-lane rural America over the past 19 years, I enjoyed the article about Walter Kirn ’83’s road trip to understand the American political divide (“Lost in the Democracy,” November issue). Not a journalist, but an excellent bar mate and listener, I have spoken with hundreds of rural residents in bars, cafés, and gas stations. Not only can many not provide local directions, as Kirn describes, they have rarely, if ever, traveled outside a 50-mile radius of their birthplace. Their view of events outside that radius has grown from disinterest to distrust, anger, and hate, fueled by talk radio and Fox political shows. Of interest to them are gas, food, crop, cattle, and tractor prices … and gun rights. Largely irrelevant are pandemics, Ukraine, and climate change.

Outside of politics, one finds warm, hardworking, gracious humans, but mention politics and they throw up a wall of defensiveness and conspiracy theories. Unable to justify their opinions, they claim to being treated condescendingly. They go with gut feelings, and talk radio and Fox resonate with those feelings, feeding their anger and hate. To pleasantly converse with rural Americans, one must avoid politics entirely, and frankly, that goes for plenty of urban Americans, too. That is not a true solution to our divide, but it may be all we have to prop open a door to rediscover our common humanity.

Randolph Hobler ’68

2 Years AgoDisregard for Truth and Facts

Walter Kirn ’83 at first seems to thread the needle between the parties, but then explodes any possible support of truth and facts when apologizes ex-President Trump as “a guy who felt he wasn’t getting his chance to be president.” I need only cite the proven 15,000 lies Trump has spewed out, much less his other proven unethical, criminal behavior, to put to bed any connection to truth and facts.

When given the clear opportunity to weigh in on Jan. 6, Kirn dodges and deflects saying, “I don’t feel that I’m in the business of moralizing about the American story.” What? He’s been given the chance to condemn Trump for the proven worst attack on democracy in our history, and he is silent? How dishonest.

Among other great values of a Princeton education was being ingrained in a deep appreciation for truth and facts in every single course we took. I am deeply disappointed that a fellow alumnus has so trucked in the disinformation barrage emanating from the likes of Fox.

Ron Hall ’76

2 Years AgoA Point of Reference

I have been a “road warrior” most of my life since Princeton, both work and travel. I live about 6 hours west of Livingston and have been through there a number of times over the years — first drove through there when Montana had no daytime speed limits.

It has a population of about 8,000 now, and for many years it was where many rich tourists got off the train at the historic train station (designed by the same architects as NYC Grand Central Station) to take a tour down through the Theodore Roosevelt Arch into Yellowstone Park. The station no longer handles passengers and houses a local museum. Because the town is on the north side of I90, most of the Yellowstone traffic (and business) does not go through there.

Livingston lies on the banks of the Yellowstone River and was a major service yard for the Northern Pacific Railroad, located midway between Minneapolis and Seattle. The railroad left behind a 2-mile-long plume of diesel fuel, lead, asbestos, and chlorinated solvents in the local ground water, impacting the town and the river. I suspect Mr. Kirn was drinking bottled water during his interview. FYI, the Northern Pacific was bought by the Burlington Northern which is now owned by Warren Buffet.

Ever since Robert Redford filmed A River Runs Through It in the area a number of years back, it has experienced a real estate boom. Some of the more famous buyers are noted in the article. The movie also brought in a slew of fly fishermen tourists. I would be interested if they eat what they catch.

Like many parts of America, Livingston looks great on the surface, but it needs a lot of work to clean it up.

Jim Govert ’89

2 Years AgoKirn Should Heed His Own Advice

TL;DR version:

Walter Kirn ’83 is correct to note that Princeton is best when looking outward instead of inward. I hope someday he can fill the apparent emptiness inside and do the same. I am convinced Princeton, like most worthy institutions, rewards those willing to jump into the deep end but cannot do much for those who merely dip a toe because they are afraid they might look foolish if they get all wet.

Wordy version:

I have been happily introduced to various thoughtful and delightful fiction and nonfiction authors in part because of their affiliation with Princeton, from F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 to John McPhee ’53 to Michael Lewis ’82 to Jennifer Weiner ’91. Then there is Walter Kirn.

Unfortunately, the through line in what I’ve managed to digest of Kirn’s work is his apparently pathological need to be accepted, perhaps even loved, by groups he could just as easily have joined if he were slightly more self-aware or a wee bit more courageous. Instead, he recounts episode after episode demonstrating that his mostly self-imposed level of alienation (whether from his colleagues, a certain number of women, the environment, or his classmates) that rivals the grotesque levels usually reserved for fictional characters — think overprivileged, grumpy, and oblivious white guys like J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield or John Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom or Richard Ford’s Frank Bascombe or even Kirn’s own clearly semi-autobiographical Ryan Bingham. In other words, the exemplars of those annoying guys who observe the world and generate snark from the sidelines, but cannot bring themselves to participate in the game as that is a bit louche or a bit too bourgeois (or violates some similar snotty Francophone concept). And then these navel gazers have the gall to wonder aloud why it’s all gone sideways.

Alas, it is simply too wearing and wearying to read prose that amounts to transcripts from Kirn’s self-directed therapy sessions. I doubt I will force myself to pick up his latest offering, even if his observations on our cultural divide prove correct or useful. It’s a safe bet he will manage to write about being alienated from both the coastal elites and from the working class in the heartland even as those groups are alienated from each other. Do tell.

But why am I spending time ranting in PAW about all this instead of leaving you all alone and just ignoring an author I don’t like reading? Well, that last bit is part of it — I’ve now read enough Kirn to be unhappy with his overall efforts and cocky enough to think I know why. And of course there is no denying I graduated just over 33 years ago, so now I am and old and occasionally grumpy alumnus and so obviously primed to write nastygrams in PAW about my glory days. But besides being in the cranky and creaky demographic sweet spot, I also I feel his accounts need a corrective that did not appear in the article and so wanted offer my own Princeton experience as one minor counterweight leading to a different.

Like Kirn, I showed up at Princeton in the ’80s (just a bit later than he). And like Kirn, I arrived from a “nonstandard” Ivy Leaguer background at time even for those us somewhat privileged white males. In his case, a Minnesota rural community not too far from Minneapolis/St. Paul and in my case a bedroom community near Toledo, Ohio, another industrial midwestern town. And heck, my parents had dropped out of college without finishing (though that hardly defines them) and there were thus no legacy admissions like Kirn’s for me or pioneers to blaze a trail for my college experience. Nor did I prep at a metro New York or D.C. feeder school or elite New England boarding school. I merely attended an all-boys Catholic high school — one with no AP courses and no crew or lacrosse, but with a city champion football team! While many of my suburban peers were college bound, not too many of my relatives were. And vanishingly few of my high school compadres were looking at fancy pants places like Princeton for higher education. I know I arrived a bit anxious, concerned I might be out of my depth. So I believe I do understand a bit how Kirn felt coming to Princeton and I was once sympathetic. But no longer.

Unlike Kirn, I was not sophisticated enough to hide my fears by hanging back and making dry or wry comments later. My somewhat blunt approach was to lurch around trying just about everything on the both the academic and nonacademic menu to see if I could get better, smarter, and stronger (and never remembering to try to impress folks by sending a dish back as purportedly uncooked!). I was the rube who did all the reading, even the reserves and the stuff that was not going to be on the test. I joined some clubs and quit the ones I did not like. I played intramural hockey and pickup basketball as varsity sports were beyond my skills. I tried and mostly failed at dating. I majored in politics and read enough political theory to want to change the whole damn world. I protested against the unfairness of the times. I got up pre-dawn and delivered newspapers from Mathey College down to Lake Carnegie (in addition to my work-study job at DFS) so I had some entertainment money in addition to my share of tuition contributions. The good news is that with such a diverse and spotty set of achievements, I was easily able to avoid the pure careerists and the grade grubbers and the kids who spent their parents’ money clubbing in NYC every weekend or passed out in an eating club taproom.

At my best, I kept myself open to learning from those around me who were smarter and more rigorous in their academic efforts (or both!), whether professors or classmates or grad student TAs. I took 100- and 200-level courses in at least half-dozen departments from faculty geniuses and did not worry that my understanding and performance varied widely and thus my GPA was a bit lower than it might have been with a few more gut courses to boost the numbers! I drank deeply from the well of amazing intellectuals (and yes even from a few taps on Prospect Avenue) and argued late into the night about matters of deep significance with folks who are my friends to this day. Basically, I immersed myself instead of trying to look cool or snipe from the safety of a sarcastic or cynical reserve. A ticket to lifelong learning and engagement was my reward for the small price of occasionally looking like a fool or admitting I did not know it all. And it may be too hokey to be believed (or so trite it does not bear repeating), but all that doubt I had as a freshman was gone by graduation, replaced by a mostly well-earned confidence.

By contrast, what a sad four years Kirn seems to have had, obsessing over the small minority of the socially-adept and avoiding so many of the best things on offer at Old Nassau. Left feeling judged and somehow not worthy. And what’s worse, that approach borne of fundamental insecurity and a stultifying status consciousness seems never to have left him. It did not have to be that way, and even now it could still be different. Hanging around with Greg Gutfeld will not patch the hole in Kirn’s soul; hopefully, he will yet find something real in his travels or at home that does and write about that down the road.

Margaret Ruttenberg ’76

2 Years AgoThere’s Condescension and Then There’s Lying

Regarding the story on Walter Kirn ’83: I agree that the tone of Democratic Party leaders toward middle-class Americans who do not support them can be condescending. I despise condescension, but I despise being lied to even more.

Alas, when someone is really good at telling me lies I want to hear, I have trouble spotting them. I believe that that is something Republican Party leaders have perfected in the case of many middle-class Americans, especially regarding their economic best interests.

Many of the lies involve deflecting blame onto others: pregnant women, migrants, anyone identifying as LGBTQ, anyone who does not want to own a gun in order to feel safe, anyone who believes that only secular education should be at public expense.

The biggest lie, though, is that massive tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations will ever benefit anyone except the wealthy and corporations. The last 40 years have made that amply clear. Only more progressive taxation, a robustly nonpartisan judicial system, and a firmly secular education system can benefit the vast majority of middle-class Americans, regardless of their color, creed, or gender.