The essay below was first published in 2003, when Stella Daily Zawistowski ’00 was a relative newcomer to competitive crossword solving. Last month, she finished fifth in the top division at the 2013 American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, her best performance to date.

Sitting on the couch at Campus Club, enjoying a lazy Sunday afternoon with the New York Times crossword when I ought to have been working on my thesis, I hardly imagined it would come to this. But here I am in the middle of March in Stamford, Connecticut, for the 26th annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament – the Olympics of puzzledom. Nearly 500 competitors, including a handful of Princetonians, have come to duke it out on small black-and-white grids; the top prize is $2,000 and bragging rights for a year. Huddled around long tables, we pack a hotel ballroom, at first chattering noisily about all things cruciverbal. The room will become utterly silent once the solving begins.

Competing in five skill divisions (in addition to age and geographic divisions), we each will solve seven puzzles of varying difficulty over the course of the weekend. To have even a hope of finishing well, one must be both accurate and fast. Consider perennial top-five finisher Ellen Ripstein, who regularly does the New York Times Sunday crossword in approximately 15 minutes. For years she was referred to as the “Susan Lucci of crosswords” for her habit of finishing in the top five yet never winning. Despite her speed, Ripstein has won just once, in 2001. That’s a measure of what we are up against.

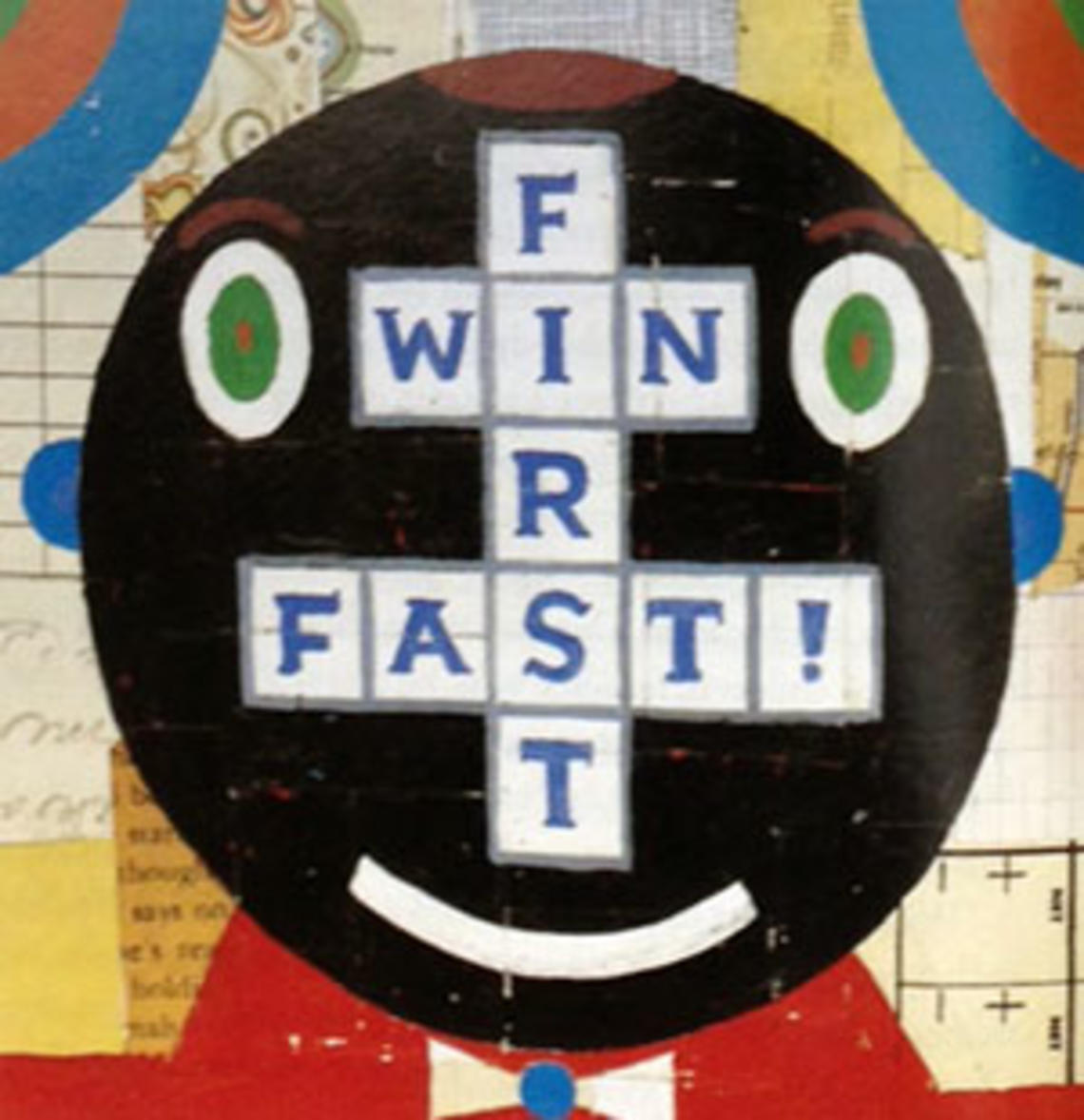

The highlight of the event is a showdown between the top three competitors of each of the top three skill divisions as they solve oversized grids on dry-erase boards in front of an audience. The pressure is high; there are moans and groans every time someone makes a mistake, though the finalists, wearing white-noise machines, are oblivious both to the audience’s reaction and to the pun-laced commentary given by Merl Reagle, puzzlemaker for the Philadelphia Inquirer and San Francisco Chronicle. The top contestants are given just 15 minutes to work through grids of difficulty ranging from medium to insanely hard, but all will finish with time to spare. It’s a treat to watch.

We all have come to the tournament with different expectations. Kiran Kedlaya *97, who has finished in the top 10 twice, and Tom Weisswange ’94, who is here for his ninth tournament, are veterans. New York Times city editor and first-time competitor Mike Molyneux ’76 thinks “it will be like signing up for the U.S. Open and playing alongside Tiger Woods; I’m hoping not to embarrass myself.” This is my third tournament; in addition to the four puzzles a day I usually solve, I’ve been working my way up to 15 daily-size grids (which usually require between three and seven minutes each) per day in the month preceding the competition. My normal solving time for the larger New York Times Sunday puzzle is 30 to 40 minutes, more than respectable in the real world but unremarkable here.

Will Shortz, crossword editor of the New York Times, presides throughout the tournament; the seven puzzles he has chosen for us are a mixed bag. The first is an easy warm-up, but we move right along to a pair of grief-inducing grids, one by Wall Street Journal puzzle editor Mike Shenk, the other by Bob Klahn ’66, a constructor known for his difficult puzzles. (A recent Klahn grid included the clue “Dead giveaway” for ESTATE. Groan.) Klahn is proud of his reputation; when I tell him he’s my personal nemesis, he grins and says, “Those are words of love.”

At my first tournament in 2001, the puzzles seemed of medium difficulty at best, perplexing and impossible to finish at worst, but really, none of the crosswords here is more difficult than, say, a New York Times Thursday. (Times puzzles increase in difficulty from Monday through Saturday; the Sunday puzzle, often cited by those who are not crossword geeks as the toughest, is actually less difficult, though larger, than Saturday’s.) I blow through the first grid in a mere four minutes; the hardest puzzles require no more than 20 minutes. Yet I have no delusions of grandeur; I will not even come close to the big silver trophy and the $2,000.

As it turns out, my performance has earned me a very respectable 49th place, far better than the top-100 finish I was hoping for. I take home first prize in my skill division (admittedly, it’s Division D, out of A through E) and third place for those age 25 and under. Yet the disappointment is bitter: I have missed the Division C finals by a mere five points on a total score of 11,060. Just one fewer mistake or one minute faster would have earned me a place on the dais, solving a grid for an audience. Curse you, Bob Klahn! As usual, it is his puzzle that has cost me my shot at glory.

Most of the solvers in the room knew they had no chance of going home with so much as a divisional trophy, let alone the top prize. So why bother? Some, especially Connecticut locals, come for the first time because they’ve heard about the tournament in the news and figure it will be fun to take part. Others, repeat contestants, show up just to see how well they stack up. But the soul of the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament is the people. We are puzzle geeks, each and every one of us, and if there’s anything we savor as much as a really great crossword, it’s meeting others who share our obsession. The room is packed with brilliant people, such as Tyler Hinman, the 18-year-old college freshman who came out of nowhere to win the Division B championship, and Doug “The Iceman” Hoylman, a six-time tournament champion who demonstrates an uncanny calm under pressure. The in-jokes fly: We talk about taking vacations by the YSER River in Belgium, eating OREO cookies when we get there, and using ALOE lotion to cure a sunburn. (Due to their letter combinations, all three words appear repeatedly in crosswords.)

At the awards banquet, I lunch with Ellen, Tyler, and Kiran, among others; Ellen, who has just taken a job as an editor with Random House, says she’s looking for young constructors for a new book and that she’ll be calling me. Whoopee! Tyler is smug about his astonishing success and yet so genuinely enthusiastic that he’s not the least bit annoying. And Kiran, as it turns out, sang with me in the Glee Club – no wonder his name looked so familiar! As Bob Klahn, who returns year after year both to construct puzzles for the tournament and to take part in the judging, says, “Judging is actually pretty doggone tedious; I keep coming back because of the people.”

Thanks, Bob. You may be my nemesis, but I couldn’t have said it better myself.

No responses yet