Welcome, Class of ’23!

Diverse class hears cautionary words on ‘existential crisis’ of digital fixation

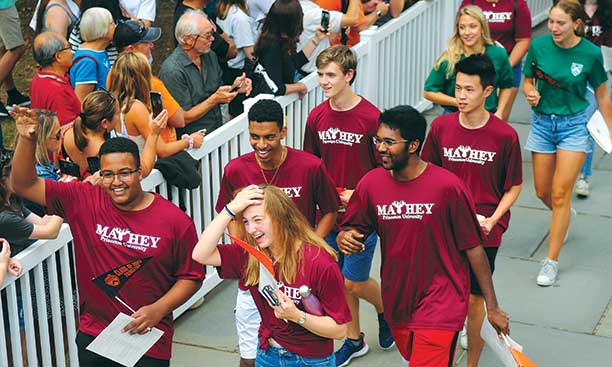

Clad in the rainbow hues representing their residential colleges, members of the Class of 2023 entered the University Chapel Sept. 8 for the official beginning of their Princeton careers. President Eisgruber ’83 welcomed the class with an homage to the late author and professor emerita Toni Morrison, inviting the freshmen to engage, as she said in a 1996 address on Princeton University, in “encounters and collaborations among and between strangers from other neighborhoods, and strangers from other lands.” (See page 24 for Morrison’s address.)

Hailing from 49 states and 49 countries, the 1,337-strong Class of 2023 is one of the most diverse classes to have walked through FitzRandolph Gate. Beyond geography, it includes students from a wide range of socioeconomic, racial, and gender diversity: Close to a quarter of the class is Pell Grant-eligible, more than half are women, and nearly half of the students from the United States identify as people of color.

Ashley Teng ’23, of Washington state, enjoyed the interfaith component of Opening Exercises. “I expected diversity for sure, but I’m still surprised by the ways Princeton incorporates that,” she said. Classmate Hannah Diaz, also from Washington, said she’d “never been in a chapel and heard things from other religions — so that was really cool.”

For many freshmen, small-group experiences — Community Action, Outdoor Action, and Dialogue and Difference in Action — stood out as opportunities to have the kinds of collaborations Morrison exhorted.

“It was good to be in a community that was working for a similar purpose,” said Tom Olson ’23, a Massachusetts native who went on a backpacking trip in New York. Teng had similar thoughts about her experiences on a Community Action trip focused on hunger and homelessness. “We bonded really well,” she said.

For Marilena Zigka, a freshman from Thessaloniki, Greece, Outdoor Action gave her a chance to realize “that you can survive without your phone.”

That observation seemed particularly relevant given the topic of this year’s Pre-read book, Stand Out of Our Light, which was sent to incoming freshmen to read during the summer. Written by James Williams, a research associate at Oxford University, the book argues that technology in the so-called digital-attention economy — a landscape in which tech companies invest large amounts of time and resources into keeping people online — is distracting individuals from living lives aligned with their values and goals. (For a Q&A with Williams, see page 15.)

During the annual Pre-read discussion on the evening of Opening Exercises, Williams spoke alongside neuroscience professor Sam Wang and computer science professor Jennifer Rexford ’91 in a discussion about the “existential crisis” posed by the digital-attention economy.

In an environment of “information abundance,” Williams implored the freshmen to ask themselves, “Why am I attending to the things that I am attending to?” when using personal technology. Rexford encouraged students to take courses and participate in campus events related to the electronic devices that affect “pretty much every aspect of modern society.”

Many hands shot up as the discussion was opened to students: One tech enthusiast asked how a website such as YouTube — home to “so much good information” — could reconcile its useful educational capacities with the potential for distraction. Another wondered how socioeconomic divides might create unequal challenges for users to self-regulate their online behavior. (“Responsibility affects people disproportionately,” said Williams. “Fixing the system in a systemic way is a matter of social justice.”)

Other students focused on the political aspects of Williams’ proposed remedies, which include more government regulation of tech companies and involving consumers in the design of the technologies they use. One student pointed out that government regulations are not foolproof, while another observed that tech companies’ profit motives in grabbing users’ attention were in line with the demands of the free market.

Olayele Aluko, a freshman from Lagos, Nigeria, said he had worked to use social media less after hearing that apps like Twitter and Instagram make it harder for people to finish entire books. “I like the fact that [Williams] says that technologies and their companies and intentions are not what they seem, and you need to regulate yourself,” he said.

But for other students, it appeared that the discussion would not have much effect on screen habits.

Derek Nam ’23 of Philadelphia, who described himself as “the average person in the attention economy,” said he left the session without an answer to the question: What’s next? “I read the book, but I still went on my phone afterward,” he said. “I’m still addicted to the internet.”

No responses yet