What I Learned: Failure is an Option

If this quotation from Henderson the Rain King — part of the narrator’s introduction of his sorry self to the reader — is familiar to you, then maybe you studied English at Princeton, as I did. In any event, if you’re reading this, chances are pretty good that you studied something at Princeton. And if that’s the case, and if you’re anything like me, then you might understand why that particular line, of all the lines in Western literature, sometimes resonates so ... resonantly.

If you already know me — and some 20 to 23 of you do — then you know that I’m not one inclined to look on the so-called “bright side” of things. While an optimist might think, “This glass is half full,” and a true pessimist might think, “This glass is half empty,” I’m likely to think: “There’s too much gin in this glass and not enough tonic.” Or vice versa. And then I might post about its shortcomings — and my own as a mixologist — at length on Facebook as I sip my disappointing drink.

Is it not our destiny — collectively but also individually — to change the world? Isn’t that why we attended Old Nassau — to make great waves and pose many rhetorical questions?

Indeed, in recent years, without realizing it — and without intending to — I’ve developed a social-media persona: “Guy Who Indignantly (But Humorously) Keeps Everyone Abreast of His Many and Varied Failures.” If I don’t have any good news to share, I figure, I might as well let my friends, acquaintances, followers, and cyber-admirers — along with a handful of government agencies, foreign and domestic — know about the bad news, in my own idiosyncratic manner. No news might be good news, but bad news — not tragic news, certainly, but run-of-the-mill, garden-variety, zero-fatalities bad news — is decent entertainment, and especially when that bad news is mine to deliver.

Not that it’s all bad news, of course. It’s just never the kind of news that maybe too many of us think we should have, at least once if not regularly: the promotion to partnership or C-level, the election to public office, the receipt of a prestigious award shaped like a tiny person or a giant coin, the naming of a campus building in our honor, the acquittal on all charges.

For aren’t we Princeton graduates? Is it not our destiny — collectively but also individually — to change the world? Isn’t that why we attended Old Nassau — to make great waves and pose many rhetorical questions?

With graduation on the horizon in 1995, I applied to eight law schools. Seven turned me down. If you were in my class at Princeton and you attended law school from 1995 to 1998, there’s a good chance that you got in where I did not, but I harbor you no ill will whatsoever. To the contrary, I hope you made the most of the opportunity.

But it was in law school, immediately after Princeton, that I began to perceive that my undergraduate vintage prompted others to be at once impressed and curious why I wasn’t Somewhere Better. Why was I among them, who had come from schools that are not Princeton? (Answer: an underwhelming college transcript and an LSAT score that still dissatisfies me today.)

After law school, I was not employed by a Big Firm. (With my personality, I would not have lasted 30 minutes at one, anyway.) While I interviewed with Small Firms, I considered trying to find work doing Something Else. Shooting for the moon, I emailed the recently crowned editor of The New Yorker, a member of the Princeton Class of 1981 whom I won’t embarrass by naming. I did not land among the stars, however. Although my unsolicited email led to an invitation from Human Resources to visit the Condé Nast offices in Manhattan, no job offer was forthcoming. (In the two decades since, I have managed to get a piece into Daily Shouts, but just the one.)

So I did practice law for 10 years — at almost as many different Small and Medium-Sized Firms — and I was on track to make partner at the firm I worked at last ... had I not decided to stop practicing law, as one does. That’s on me.

And then not much out of the ordinary happened until a couple of years ago, when I was a contestant on NPR’s Ask Me Another. I made it to the final round, but my opponent beat me to the buzzer in sudden-death overtime. I’d say that I was all thumbs, but being all thumbs might have helped me.

Thus, as of this writing, I have not become famous. I do not expect ever to be famous, strictly speaking, nor infamous, for that matter. I don’t expect even to be semi-famous, circumfamous, epifamous, or parafamous. I might at some point have a brush with greatness, so to speak, but probably not a full set of toiletries with greatness. The only thing celebrated about me is my birthday, and that’s only in some years. I am, by all reckonings, a man of modest achievement despite grand aspirations — or perhaps because of them. Yet I am proud of my accomplishments, such and few and humble as they are.

For instance, while I have not achieved my dream of having a novel published, even though I studied with such luminaries as Joyce Carol Oates and Russell Banks, I have written four novels, plus another two novellas — and a collection of stories that prompted a cease-and-desist letter from the literary estate of P.G. Wodehouse. (We settled our differences out of court. That in itself might be considered a brush with greatness, come to think of it, although at the time it felt more like a sucker punch from beyond the grave.) Those are accomplishments, to be sure, I try to remember to remind myself almost every day.

Thus, as of this writing, I have not become famous. I do not expect ever to be famous, strictly speaking, nor infamous, for that matter. I don’t expect even to be semi-famous, circumfamous, epifamous, or parafamous. ... Yet I am proud of my accomplishments, such and few and humble as they are.

Moreover, I am a successful “family man,” I believe the term is. I married a lovely woman (who attended a college that could not be more different from Princeton; her school was founded just four years before I was born). There was no announcement of our nuptials in the “Weddings” section of The New York Times, but I was just relieved it wasn’t mentioned in the “Corrections” column. We have two terrific children, and we also have a small, young, languishing business together. I suppose I could ask my wife to promote me to an executive position in our company, but I might want to wait until I’ve brought in more work from paying clients.

Oh, and in the 20-odd years since graduation, I’ve put on only 20-odd pounds, and that is an enviable feat, I understand.

For these reasons and others, there will never be a PAW feature story about me, I’m certain. My name does appear in the Class Notes pages every few years, though, and that’s pretty good, too. Because what I’ve learned, out here in the Real World, failing at so many things so much of the time, is this: The people who know you want to know what you’re up to, whatever you’re up to. Your friends don’t care if you haven’t (yet) changed the world. In any case, they won’t be disappointed to learn that you haven’t or won’t. You don’t need to discover, cure, solve, or even publish something to be accomplished, or even just interesting. There are many and various ways to succeed after college, even ours.

And when all else fails, when someone asks me these days, “Shouldn’t you, a Princeton graduate, have done Something Great by now?” I say: “Well, I do know people who are doing great things.”

And then, with great pride, I tell them about some of you.

2 Responses

David Hingston *76

6 Years AgoLife Stories

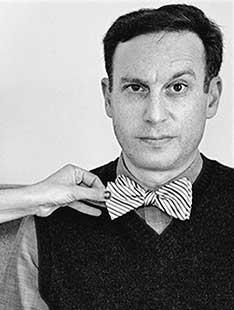

Even without knowing what Dr. T. Berry Brazelton ’40 did for pediatrics, or even for babies, I could tell from the cover photo that the man was really something. Both components of this issue, Matthew David Brozik ’95’s essay toward the end and the cover photo (and lovely Brazelton appreciation), fit together movingly. I admire both Brozik and Brazelton very much.

Norman Ravitch *62

7 Years AgoGreat!

This piece reminds me of the song Brian sang while dying on the Cross in "Life of Brian": Look on the bright side of life!