What I Learned: Science and Humanities, Doctors and Torture

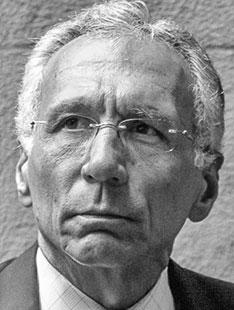

To paraphrase Dickens, Princeton was the best of times, and it was the worst of times. The strains of late adolescence and early adulthood, the looming cloud of the Vietnam War, and the angst and chaos of the social and environmental changes have lingered since graduation and paradoxically inspired my career. I have felt compelled to search for better solutions to the political and social upheaval that divided the country in the 1960s and has re-emerged today. After taking an ROTC scholarship to pay for college (I did not support the war, but felt obligated to serve in the military and had deep loyalty to our country), I enjoyed a long Army career as a military physician.

I am struck by how today’s environment revives the polarized, impassioned, and uncompromising mindsets dominating my student days. Then, the daily tumult and commotion almost unraveled the social fabric of the campus and the nation. The program in Science in Human Affairs at Princeton bridged the gap between the hard sciences and humanities and prepared me to wrestle with the contradictions and complex political and professional challenges. Half a century later, it still does.

Perhaps because my undergraduate experience was so unsettling, Princeton had a profound impact on my work. After medical school, I specialized in psychiatry, as the mental-health field is an ideal laboratory for science and human affairs. Since 9/11, an array of issues has emerged, including participation of health-care providers in interrogations, harsh treatment of accused terrorists, medical care and support to detainees imprisoned at Guantánamo, force-feeding detainees on hunger strikes, and assessing the mental responsibility of young Muslim men and women recruited by the Islamic State. The shifts in roles and responsibilities in national security involving psychiatrists and psychologists have obliged clinicians to assert their ethical and moral principles more forcefully and constructively.

A defining moment came in 2004, when I confronted the evidence of abuse and mistreatment by American soldiers at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. When I was interviewing for the position of principal deputy assistant secretary for health within the Department of Defense, the White House staff wanted to know if I condoned harsh interrogations and torture. Of course I didn’t! I was appalled by the unhealthy silence and glib reasoning by the senior leadership of the Defense Department over such unprofessional conduct. Even more alarming were the revelations that physicians, psychiatrists, and other mental-health professionals had assisted with interrogations that bordered on torture. Torture violates fundamental ethical principles of military medicine that had been drilled into me from my first days as an Army medical intern in 1974.

Over the years, I have agonized over reconciling my roles and responsibilities as a physician and military officer and am the only retired Army Medical Corps general to speak out publicly against torture, abuse, and Guantánamo.

I advised the White House and Defense Department that if I received the position, military medical personnel would not participate in nor condone any conduct that violated the Geneva Conventions; I would hold military medics responsible to report any activity that looked like torture or abuse. Not surprisingly, I did not get the nomination, but I published an op-ed in The Washington Post opposing the conduct of the military at Abu Ghraib.

Then, an unexpected turn of events landed me in Guantánamo in 2008. Legal teams representing prisoners asked me to assist as an expert consultant. I felt highly ambivalent. On the one hand, I had pledged to protect our nation against all enemies, foreign and domestic. But as a physician, I had pledged to care for all who were hurting and needed help. Facing detainees who were tortured because they were our enemies, sometimes with the aid of military physicians, I felt I had entered a domain in which the old paradigms ceased to apply. Perhaps that is one of the fundamental problems with Guantánamo, where I have spent cumulatively a year since that first trip.

On that trip, in December 2008, I met Omar Khadr, who by then had been detained for six years after being captured at 15 in Afghanistan and accused of killing a Special Forces soldier. The firefight happened when Omar had been a virtual hostage on a crude compound in the hills of Afghanistan, where his father, who had connections to al-Qaida, had farmed him out to translate for expatriate Libyans making explosives. Truth be told, Omar didn’t know if he had killed the soldier, as he had no memory of the firefight and suffered a concussion when the shooting broke out. But in the bizarre universe of Guantánamo, he would confess to throwing the fatal grenade and shorten his prison sentence in a plea bargain.

Since then, I have talked with many detainees who were held in the CIA black sites and subjected to “enhanced interrogation techniques,” the euphemism for torture. I have evaluated or reviewed case records of many others and confirmed that a large majority shipped from Afghanistan to Guantánamo had nothing to do with the Taliban; they were in the wrong place at the wrong time or sold for bounty by rival tribes to an unsuspecting American military. I have spent many weeks in and out of the Guantánamo Military Commissions courtroom with the five defendants accused of the attacks on the World Trade Center on 9/11, and hundreds of hours with the nephew of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the so-called mastermind. No doubt, the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon fundamentally changed our country’s national-security strategy and conduct of war. Understandably, fear and anger mobilized the government to respond aggressively with a broad array of countermeasures. But I have also come to know many detainees and have been exposed to their thinking and motivations. Some could still threaten our national security. Others never did and never could have. The sloganeering about terrorist threats and perpetrators is deceptively simple and politically exaggerated. Emotion has undermined our national military strategy.

Over the years, I have agonized over reconciling my roles and responsibilities as a physician and military officer and am the only retired Army Medical Corps general to speak out publicly against torture, abuse, and Guantánamo. The phenomenon of modern warfare has launched mental-health practitioners onto the front lines in the fight against terrorism, from interrogations to the care and feeding of captured combatants. It has pushed clinicians to think beyond the principle of “first, do no harm,” into unprecedented predicaments that challenge ethics and principles. I have publicly and vigorously challenged health-care providers to ponder the duties and obligations embedded in their clinical and forensic practices to the realities of the global war on terror.

My work as a physician and Army brigadier general has been grounded in the principle that violating human-rights principles weakens the effectiveness of the military mission; undermines the broader political, economic, and social strategy in support of national security; and breaches the fundamental principles of all health professionals. The military profession, answering to civilian and elected authority by law, is particularly grounded in basic values of human rights — with a common allegiance to the Constitution and to the founding principles of democracy. The ethical principles of the health professions are also embedded in human rights. The historical record of physicians and medics in combat attributes to them an inherent expectation to advocate for and protect human rights, no matter the circumstances and political pressures.

As a psychiatrist and Army general, I have adhered to the dictum of “Princeton in the nation’s service” with assiduous attention to the educational principles of probing challenging problems, asking tough questions, and exercising personal and moral courage as best as I can. Mental-health issues span multiple sectors of American society, affecting prisons, criminal conduct, education, employment and productivity, veterans, national defense, social concerns (bias and prejudice), and many more. No other specialty has such a wide and diverse impact, and it begs for coordination and collaboration.

My Princeton years were not idyllic, and I left the campus feeling both enriched and deeply aggrieved, not returning for 20 years. I vowed that whatever direction my career unfolded, I would not lose sight of the deep personal concerns and sentiments of the men and women around me and the thankless service of the Americans on the front lines. Working in Guantánamo and human rights, and as a senior Army leader and physician, I’ve labored to fulfill in word and deeds the good and bad lessons from my undergraduate years. I believe ardently in the power of individualism and human rights and have attempted to reinvigorate core ethical principles to serving as a military officer and clinician, and to advocate for truth in public service. American democracy and national-security strategy have been erected on the foundations of human rights, and physicians and soldiers are responsible to fervently uphold those principles.

A CALL FOR ALUMNI VOICES

Throughout the year, PAW will publish essays by alumni on a wide range of topics that could help other alumni navigate through careers, family issues, and ethical dilemmas, among other things. Essays can be serious or funny, but they should have a strong voice. Send your idea — not a completed essay — to pawessay@princeton.edu.

2 Responses

Guy K. Stewart Jr. ’62

7 Years AgoConduct and Character

Re his essay on torture, I would like Stephen Xenakis to explain to Princetonians — in no uncertain terms and with no equivocation — exactly what he means by the word “torture,” and I would like him to give us precise examples of conduct he believes constituted torture used by interrogators in Iraq; i.e., did American interrrogators hold a cattle prod to a prisoner’s testicles or to other parts of his body; did American interrogators use pliers to remove fingernails from prisoners; did American interrogators hold a prisoner’s head in a bucket of water or in the toilet until he confessed? In short, did American interrogators physically abuse prisoners, and, if so, how?

Richard M. Waugaman’70, M.D.

7 Years AgoBalancing the Obligations of Military Physicians

Thanks so much to my classmate Stephen for this moving essay. It stirs so many reactions for me. Like Stephen, I became a psychiatrist after Princeton. Although I have not served in the military, for 20 years I have been adjunct professor of psychiatry at our nation's military medical school (the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences). Several times, I have helped teach the required course on military medical ethics. The course is fantastic. Some years, though, the reactions of some students worried me. A few of them seemed to have lost their moral compass as a result of the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

Stephen has spent his career in a world that tests character in numerous ways. It is not easy to balance the obligations of military physicians to help support our troops as a fighting force and our professional obligations to our individual soldiers as well as to a range of other people, including enemy soldiers, suspected terrorists, and non-combatants on any side of a conflict.

I admire how well Stephen has threaded this needle, showing dedication, patriotism, and courage.

Stephen alluded to Princeton students' views of the Vietnam War while he and I were on campus. Many of us strongly opposed the war. But I don't know that many (any?) of us were against our troops. So many of them were drafted, as any of us could have been. Opposition to U.S. military policy at any time need not mean opposition to our soldiers. I think we're much clearer about that distinction now than we probably were in the 1960s.

When soldiers tell us they are tired of hearing "We appreciate your service," I wonder if their resentment of their chain of command is getting displaced onto well-meaning civilians. Yes, we are the civilians who elected our public officials, so we are indirectly responsible. But I also ponder the possibility that it's deeply complicated for anyone in uniform to let themselves know just how much they might resent their Commander in Chief, and others in their chain of command. (Thinking of the Vietnam War, I know some soldiers lost control over that resentment, leading to "fragging" their officers.)