What’s Next? PAW asked two writers with different views to consider the future of our major political parties. Read Ryan T. Anderson ’04’s take on the GOP here.

In the classic 1972 film The Candidate, Robert Redford played the Senate candidate Bill McKay. The film revolves around an unknown Democrat, the son of the former governor, who agrees to challenge the popular Republican Sen. Crocker Jarmon. The movie ends with the victorious McKay asking: “What do we do now?”

Now that they have control of the White House and Congress, Democrats are asking the same question. The fury about how President Donald Trump used his power has dominated the conversations among Democrats over the past four years. With Trump as president, it was relatively easy for most members of the party to stay united: They could focus on what they opposed, elevating the defeat of the incumbent above everything else. Even after his defeat in November, the departing president’s dangerous effort to overturn the election kept national attention on Trump at a time the president-elect ordinarily would have been the center of the national conversation.

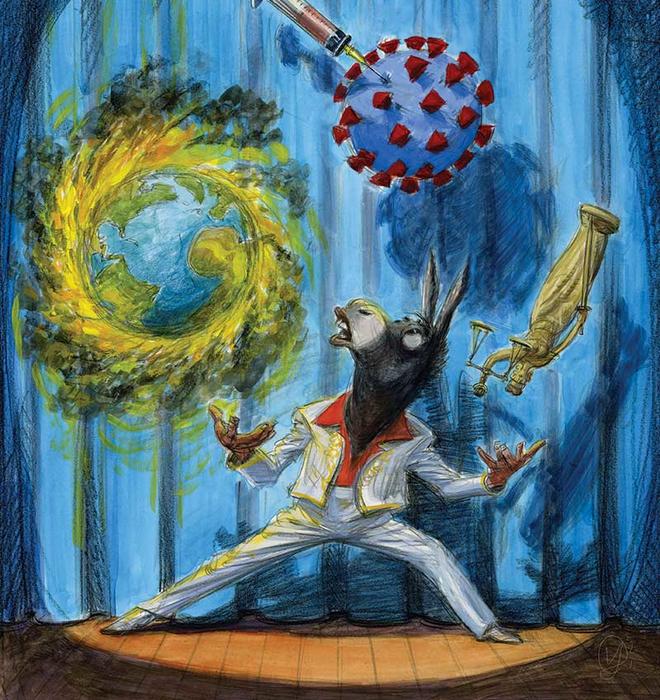

But now the Democrats control the levers of power and will face the immense challenge of governing during what is hopefully the final phase of this devastating pandemic. One of the biggest challenges Democrats face is how to deal with internal divisions.The party’s progressive wing, which has become much more robust in recent years, will inevitably find itself clashing with the growing ranks of moderates who have entered office since 2018. Each faction will perceive the 2020 election as a mandate for pursuing its way of doing business. Though fewer in numbers, progressive Democrats will point to the widespread popularity of their agenda in areas like climate change and health care. Moderate Democrats will insist that the large number of legislators who came from swing districts reflects the heart of the party. Some moderate senators have already shown they’ll use their leverage to extract concessions from party leaders. Each faction will also realize that the window of opportunity for legislating will be limited.

As Biden attempts to keep the factions united, he needs to contend with the fact that Republicans will remain a fierce and formidable force. The support former President Trump received from top Republican politicians during his drive to overturn the election revealed how far many leaders in the GOP are willing to go in pursuit of partisan power. While the Republicans suffered a huge political blow in November, losing control of the White House and Senate, in the upper chamber the Democratic majority is slim. For an obstructionist such as Sen. Mitch McConnell, this means that there is still plenty of room to block and stall Biden’s legislation. A slimmer House majority for Democrats, moreover, means that Speaker Nancy Pelosi has less wiggle room to finesse proposals that trigger internal divisions, such as Medicare for All. Meanwhile, Biden can’t ignore the fact that more than 70 million Americans cast their votes for Trump.

So, how can the Democrats survive themselves and seize the potential that exists to push public policy in new directions? In other words, what do they do now?

The good news for Democrats is that the most transformative coalitions in modern American history have overcome internal division even when faced with fierce opposition. President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition in the 1930s, which ran up against business interests that wanted to use their power to roll back his expansion of the regulatory state, consisted of disparate factions who had little in common: conservative Southern Democrats who hated unions and racial justice, farmers seeking federal support to stabilize their collapsing markets, labor leaders who wanted the right to organize, Northern machine politicians who cared most about funding for their cities, and African Americans seeking assistance from dire economic circumstances.

When pushing for the Great Society in 1964 and 1965, President Lyndon Johnson had to navigate a similar balance, with a massive civil rights movement testing the strength of the coalition, when confronted with civil rights legislation. When Republican Ronald Reagan came to town in 1980, he found ways to hold together a conservative coalition that ranged from evangelical Christians who wanted government officials to limit reproductive rights to business and Wall Street types whose main concerns were lower taxes and deregulation.

These presidents were successful because they kept public attention focused on issues that served as a glue to hold together their disparate forces as they moved policy through Congress. FDR emphasized the theme of economic security. LBJ spoke about opportunity for all Americans to join a booming middle class. Reagan turned to tax cuts and anti-communism as threads that he wove through all the elements of his support.

Democrats need to use this moment to articulate and champion the values that define their party. They must distinguish themselves from the GOP — and not just from Trump. At this moment, the most distinguishing element of the party is the commitment to governance. As a result of the radicalization of the Republican Party that we have seen over the past few decades, the GOP can no longer claim to prioritize the needs of governance or our democratic institutions. With President Biden, a figure with deep experience in Washington who has a strong belief in the virtues of our constitutional system, Democrats have an unusual opportunity to demonstrate that they are the adults in the room.

Democrats also must show voters that they are the party of middle-class America. Though Trump presented himself as a populist politician who cared about struggling American families, his policies cut against that claim. With regressive tax cuts that benefited wealthier Americans and deregulations tailor-made for business, the most that Trump offered working Americans was a toxic dose of nativist and backlash politics. In contrast, Democrats must show that they will offer policy. They can tap into a long tradition that started with FDR to demonstrate that they will fight for government programs that help working- and middle-class Americans become more secure.

President Biden, who lacks the charisma of his predecessors, has issues that he can use in similar fashion to achieve these objectives.

Fighting the pandemic is the most obvious theme. Days before his inauguration, Biden announced a $1.9 trillion stimulus bill and later expressed his support for using the reconciliation process, which prevented senators from filibustering the legislation. Just as Johnson understood that he needed to complete work on the Civil Rights Act before he could free up space for other issues, Biden understands that his ability to accelerate the production of vaccines and improve their distribution would give Democrats enormous political capital by the fall. The final legislation provides money for — among other things — vaccine development and distribution, small-business relief, direct payments to American families, greater subsidies for the Affordable Care Act, and aid to state and local governments.

The most that Trump offered working Americans was a toxic dose of nativist and backlash politics. In contrast, Democrats must show that they will offer policy.

The issue of climate change presents another opportunity. The pandemic has offered Americans tangible evidence as to what happens when we ignore massive crises until it’s too late. Climate change poses an even bigger threat to the nation and the world. Climate change is also a policy challenge that impacts different Democratic constituencies. The destruction of the environment threatens educated, suburban, upper-middle-class families who care very much about the quality of life for their children. It impacts disadvantaged communities, including African Americans and Latinos, who bear the brunt of our refusal to control carbon emissions. It impacts our ability to grow the economy in sustainable ways, trapping us into older economic models while other parts of the world thrive by moving in new directions.

Finally, there’s racial justice. Biden is an unlikely president to lead the nation in tackling institutional racism. His career includes many turns away from bold civil rights policies, as he was often concerned about white working-class constituencies who did not support programs such as school integration and criminal-justice reform. But the 2020s are different from the 1970s and 1990s. Biden assumes the presidency at a moment when the Black Lives Matter movement has transformed our public debate. Responding to the horrendous images captured on social media and the overwhelming data about how our criminal-justice system disproportionally hurts African American men, this is the moment when we need to feel the fierce urgency of now, as Martin Luther King called it, to address these forms of stratification and injustice. Under Merrick Garland, the Department of Justice must become a juggernaut for policies that create accountability in police departments and eliminate discriminatory sentencing.

There are, of course, other issues that Biden can use to unite the Democratic Party, but these three policies offer a powerful mechanism to keep his colleagues on the same page.

Democrats have something else that can bind them, too. The radicalization of the Republican Party that has been building since the 1980s, culminating in the Trump presidency, will remind Democrats what the stakes are in failure. The need to move forward on unifying issues and avoid taking steps that will open the door to Republican victories in 2022 and 2024 will loom large. While for some Democrats this might mean caution, others will see it as reason to be bold and to give voters a reason to keep them in power.

No responses yet